Who are the most eclectic readers?

A new study of Goodreads data

A new study of Goodreads data in the Journal of Cultural Analytics has some interesting things to tell us about the reading habits of the most active users. Reading literary fiction falls off sharply, and this is among the most active readers.

But if some readers are strongly marked by the experience of reading classic literature in school, we found that literary fiction is not a “sticky” genre in terms of ongoing habits of reading. Most users who have early contact with classic and critically esteemed novels peel away from that kind of reading later on. Looking again at the upper image in Figure 4, we can see that the same is true for fantasy/science fiction, which drops from around 22% of the books read in the first few time segments down to 18% in the last few. Where do readers go, when they migrate away from those genres? Our data suggest that mystery/thriller is the stickiest of all major genre clusters. In the aggregate, readers tend to read more rather than less of it as the years go by.

And on the question of how omnivorous readers who say “I’ll read anything” really are… yes, self-proclaimed eclectics are often more eclectic

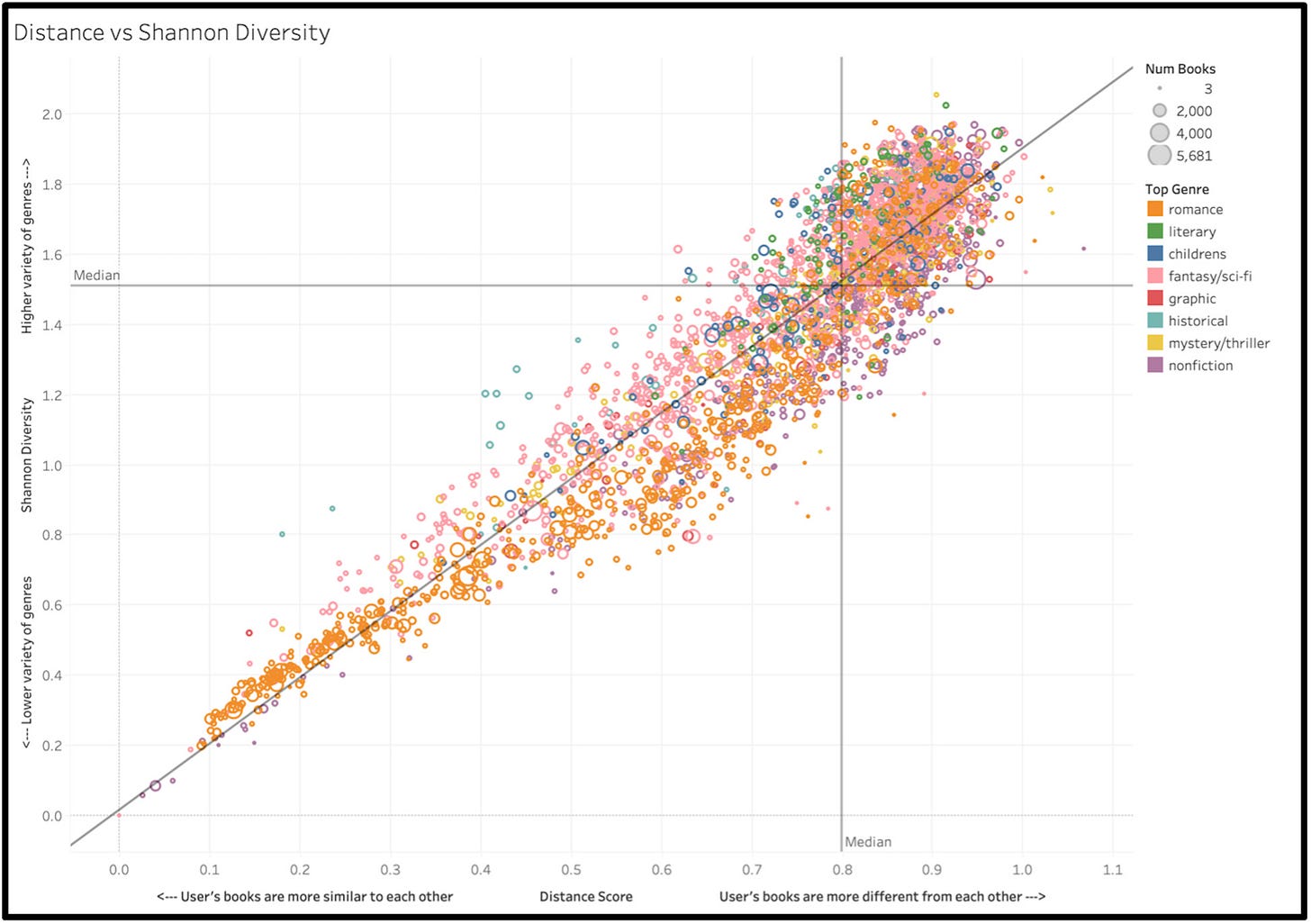

We tagged a large sample of users in our dataset whose “Interests,” “Favorite Books,” or “About Me” fields either include the actual word eclecticism to describe their reading habits, or contain self-descriptive phrases such as “I read everything,” “I read every kind of book,” or “I just love reading, I’ll read the back of a cereal box.” When we compare the Shannon Scores and Distance Scores for these 147 readers to the metrics for all other readers (including self-identified univores, readers who declare their narrow devotion to one specific genre), we do find a statistically significant difference, with self-identified eclectics a little higher on average by both metrics (Figure 7, Table 3).

but…

There are readers who self-identify as eclectics but whose eclecticism, by our measures, is well below average. An example is a longtime highly active user whose About Me field reads, “Love any kind of books. . . crazy about books.” She describes her Favorite Books as encompassing “almost all genres,” and under Interests she again declares her “love [for] any kind of books.” By our metrics, however, this reader is a clear-cut univore. Her books are shelved as 84% romance, yielding a Shannon Score of .629 and a Distance Score of .36, both well below the median scores even among other romance readers.

(Romance readers are the least omnivorous of all readers, according to this data.) The study authors do a good job of explaining all the ways in which someone’s reading might simultaneously appear to be both eclectic and not eclectic, depending on how you categorise things. Some readers, for example, read across genres, but almost exclusive read African American, or Irish, or Canadian authors. It is not always easy to say who is eclectic!

They conclude:

As long as literary scholars were content to base arguments about literary reception on comforting generalizations about “readers” who were no more than projections, idealizations, or figments of the discipline’s collective imaginary, there was no reason to bring these deep divisions to light. Andrew Piper recently demonstrated, via a sample of 3,000 sentences in which literary scholars invoke a reader or readers, just how overwhelmingly dominant that homogenizing approach has been.[25] We can rejoice in the signs of its gradual eclipse as the rise of online bookish activity and the routinization of web-scraping and other computational methods enable work in which claims about reading are supported with data on actual readers. But for this strain of research to fulfill its potential, it must truly break the bad habit of generalizing from reading as it is done in the academy, universalizing the dispositions of a powerful but restricted fraction of the reading class, or opposing that fraction to a hypostatized mass of “ordinary” readers in a simplistic binary scheme. When we wrestle with the imperfect concept of eclecticism and the many challenges of measuring it, we are pushed to develop subtler understandings of affinity and antagonism, better maps of the disparate communities of taste whose relations to one another shape the real world of book-reading.

Here’s the whole thing. Thanks to Celine Nguyen for sending me this paper.

📚 I’m not an eclectic reader and don’t apologize for it.

🔍 It seems to me Sherlock Holmes novels could be a gateway series to get mystery readers into the classics.

I'm not sure if Goodreads is your average reader. I think you have to be a fairly prolific reader to even use the site. I used it initially to catalogue my book collection, and to identify what I have read, because sometimes, especially with more obscure authors, I start getting into a new book and realise I have read it before.

I would certainly consider myself an eclectic reader. I generally read a fiction and non fiction book concurrently. The fiction tends to be in the SciFi genre, but could be anything. Non fiction likewise. I read anything from old history to autobiographies and any topic that strikes my interest. I also listen to audio books when I drive, or before I fall asleep.

Currently I am listening to Sleeping Giants, by Sylvain Neuvel.

I'm currently reading Without Warning, by John Birmingham, and for contrast, The New Penguin History of the World, which is an interesting reminder that peace on our planet, since humans invented weapons, is a fleeting thing. And of course many Substacks :)