Who's afraid of reading books?

The literati and the prestige economy

Literary discourse is in a dark phase. There is a crisis of the humanities and the English major is dead. The hype cycle isn’t working: debuts don’t break out anymore. Substack went from being a walled garden of literature to just another commercial social network heading towards enshitification. Reading the Beats is a red flag. Books are corporate products, and this big corporatisation of literature has fundamentally changed the product.

Some of these claims have a shadow of truth. English enrolments have fallen, (though that’s not such a problem as we think). And who really was the last author who made a huge breakthrough? If it was Brandon Taylor (2020) or Sally Rooney (2017) it doesn’t seem that long ago. (Is the hype cycle supposed to deliver a major breakout debut every year? Can there possible be that many excellent novels?)

But this mood isn’t original. It’s the new Amazon killed bookstores, Goodreads killed good taste, Twitter made everyone into a writer. And so on. Before that it was the death of the Western Canon and the Closing of the American Mind.

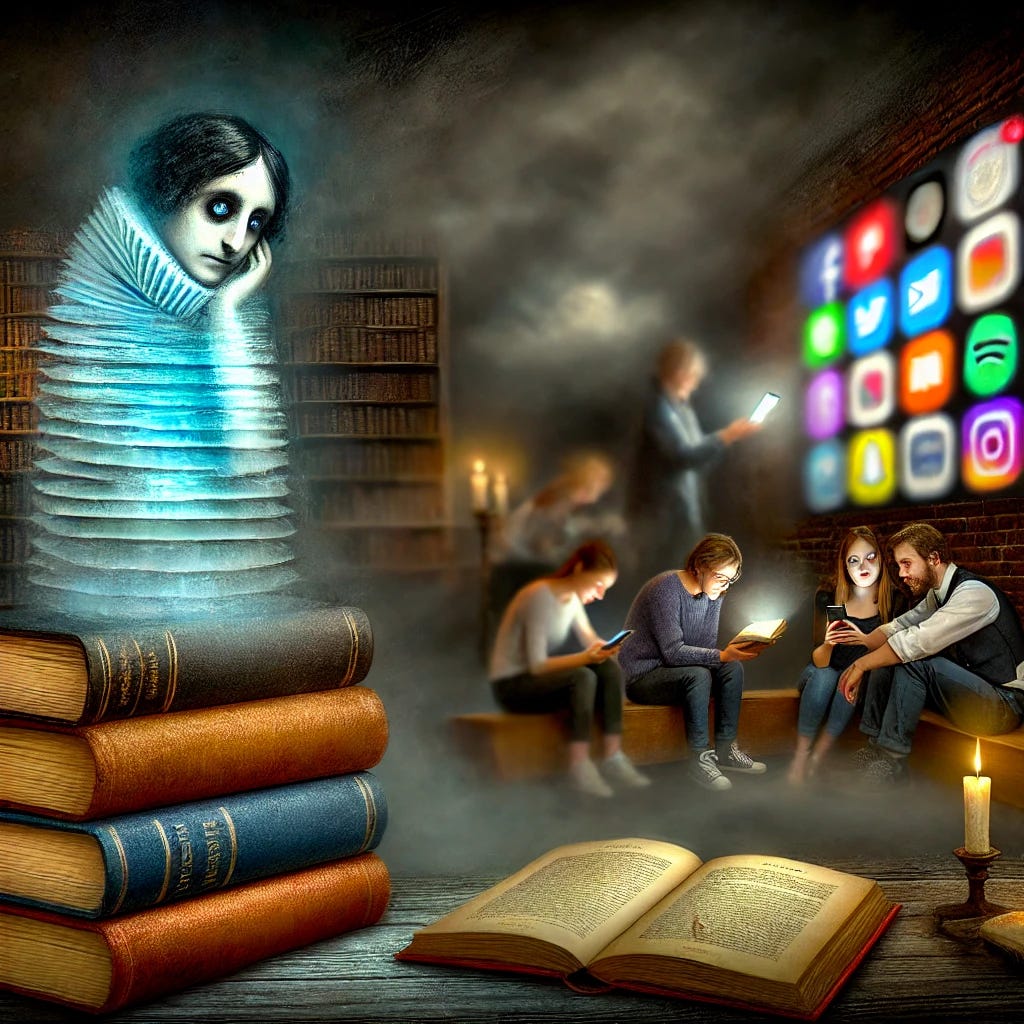

What’s really going on is that literature has lost ground to other mediums for more than a century. Radio, movies, television, and then the internet all took time away from print. People were complaining about the decline of reading in the 1960s. In the 1970s 8% of Americans didn’t read a single book a year. By 2016 it was 27%. Some reports say it is half of Americans. Phones weren’t the first cause of this trend, merely the last.

This technology shift also meant that novels became less and less central to the culture. It was still possible in the ages of James Joyce and Thomas Pynchon to write books that were important to their own times as George Eliot and Dickens had been important, but less and less so.

And the novels we get today often simply aren’t competing strongly enough for relevance. Sally Rooney is good at writing about life with the internet and smart phones but most novelists are not. Even literary critics seem to think that books aren’t very important. Lauren Oyler, supposedly the most celebrated critic of her generation, released a book of critical essays this year that was largely not about literature.

In the nineteenth century, this would have been unthinkable. Imagine the American Civil War without Harriet Beecher Stow or Victorian poverty reforms without Charles Dickens. George Eliot, like so many novelists of her time, was obsessed with the work of Charles Darwin. (Darwin himself was a Dickens and Milton obsessive.) How many novelists today are influenced by the work of scientists? How many of them are au fait with the crucial, cutting edge work from the world of ideas like Norman Rush or Helen deWitt? Many modern novelists are more likely to make their work an extension of Twitter by other means.

As well as being myopically literary, the literati yearn to be “cultural”. And that means that the literary elite is propping up a philistine supremacy. Professors tell us, in all seriousness, that Taylor Swift is the equal—the equal!—of Mary Shelley. Space is major newspapers is used to criticise people for posing with books in cafes. Young women on TikTok are mocked for their bad taste. People yak on Twitter about whether J.K Rowling understood Lolita or why Mary Oliver wasn’t a good poet. (Spoiler: she was).

So much effort is being spent on discussions that are not about reading literature. As Christian Lorentzen said recently, the literati is increasingly more interested in “the economy of prestige” than in literature itself.

All of this contributes to the erosion of literary culture that is supposed to be the subject of lament. If there is a crisis in the humanities, it is that some half of British adults no longer read for pleasure. Or in the fact that so many professional, well-educated people are more likely to read Harry Potter than Jane Austen. A literary elite more interested in bashing Goodreads and mocking social media users than in talking about literature isn’t going to solve that problem.

Naomi Kanakia wrote on her Substack recently that many of the influential people who read and promote new literature do so because they too want to one day be part of the hype cycle. But increasingly they are realising that books which are given large advances, get a lot of hype, and even, like Honor Levy’s recent debut, receive lots of reviewer attention, can simply vanish. Importantly, the books being picked to be published, Kanakia points out, aren’t all that good. As she says, “it’s neither fresh nor interesting; it’s merely cute and clever.”

This is the heart of the problem. Until more literary people—critics, reviewers, novelists—start caring most about the quality of what they read and writing honestly about it, audiences will not have the time or patience to sift through the thousands of new books published each year hoping to find one worthy of the hype. And preferring to talk about the prestige economy than about literature at some point distracts from the good work being done by critics like Dwight Garner and Merve Emre.

Internationally, fiction is doing fine. There are impressive works coming out of South America, Germany, Ireland, Japan, and other places. (I particularly liked the recent translation of the Korean novel Whale by Cheon Myeong-kwan.) Every year, contemporary masterworks are translated into English. Many works of great merit are published in English too. Percival Everett’s recent novel James is superb. Historical fiction continues to thrive with The Glutton and The Future Future. This year sees the publication of new work by Susannah Clarke and Sally Rooney.

A simple solution presents itself. Instead of obsessing about cultural issues, the literati should follow Ireland’s lead and read more books and talk about them. We have to choose to advocate for reading rather than quarrel about the spoils.

My unread book pile is out of control and you aren’t helping! Admittedly a lot of them are history books for my podcast. Anyway, The Whale arrives tomorrow 🙂

Have you read A Fraction of the Whole? Remarkable I thought.

But isn't that the whole point? Reading contemporary American literature brings neither joy nor material reward, so why do it?

I can read the Mahabharata all day long, but the world doesn't really need me to tell it that the Mahabharata is worth reading. Surely it already knows that.