UPDATE: My book about late bloomers Second Act: What Late Bloomers Can Tell You About Reinventing Your Life is available for pre order.

Amazon UK. | Amazon US. | Amazon Canada.

Three sorts of people

Everywhere I go, I tell people I am writing a book about late bloomers. And I get three responses.

Some people ask how old you have to be to be a late bloomer. The short answer is that there is no age. It’s about flourishing after you are expected to. Martina Navratilova was late for high-end tennis in her twenties. Bill Traylor didn’t start drawing until his eighties. Margaret Thatcher was right on time as a fifty-year-old party leader, but a few weeks earlier even her supporters were saying “Oh God, we can’t have Margaret.”

Then there are the many people who tell me that they are a late bloomer. Most of these stories are inspiring and some are actually about good old regular blooming. I enjoy them all (and am always grateful to get emails on this topic.) Also in this category are those who will give me examples of other late bloomers—my recent favourite is Thomas Hobbes, the only time anyone has nominated him, though sadly he isn’t in the current draft. (I lack space and does anyone else care?) If you’re very lucky I’ll write about him here one day.

Finally, there’s a group of people who ask,—why late bloomers?

Here is my answer to their question. As you will see, it is too long for parties.

Seeing the inside of recruitment

For ten years, I worked in advertising. We specialised in talent attraction. Organisations hired us to think about how to attract candidates to apply for jobs with them. My job was to work out the answer to one simple question—what makes this organisation interesting to the people they want to employ?

I spent a lot of time thinking about the labour market, who works where, and what is valuable in a candidate. Obviously, this varies from organisation to organisation, department to department, job to job. But there are trends and fashions. For the last decade, for example, much more effort has gone into designing programmes and systems of employment for mothers who left the labour force and people who are neuro-divergent. Internships for the over fifties are another new endeavour.

The more I learned about recruitment, the more convinced I became that talent allocation isn’t as good as we think. People have incredibly narrow recruiting criteria. Their intuitions guide them more than any empirical information about talent. And they are inconsistent. When organisations make use of their existing employees, they move them around and let them work more broadly than their job description: when they hire externally, this is all forgotten. People are locked out because they lack certificates, years of experience, the exact right sort of experience, and so on. Unless you are young, lacking a track record makes you less and less interesting in recruitment terms. That causes us to miss some very interesting people.

Being irascible by nature, I was now pointed towards what I felt was a big hole in our knowledge of talent:—people who haven’t succeeded yet, but maybe they will, as Tyler Cowen put it in his interview with Tim Ferris.

And this intersected with the way my own career had caused me to think about myself as a late bloomer.

A diversion into my past

Before advertising, I had a patchy career. I sold shirts on Jermyn Street. I worked as a teaching assistant with a class of eight year olds who had failed the entrance exam to their next school. I tutored people who literally didn’t know Winston Churchill from a hole in the ground or that Henry VIII and Queen Victoria were hundreds of years apart. I blogged for an immigration law firm. And I worked for Liz Truss, before she was famous. (Oh Liz, what happened?)

The common thread was that I wanted to be a writer. Often, when I applied for pure writing jobs, I was told I was more of a researcher. “You seem to be interested in the ideas,” they would tell me. As if writers were mere word shufflers who were not interested in ideas. At one point I thought I would get a dream job as a speechwriter. Then I went to work for Liz. (If you want to hire me as a speechwriter, or any other kind of writer, get in touch...)

Like many of the late bloomers I have studied, I had a meandering career and was deeply interested in something that was slightly outside my employment. In advertising, I became the person who interviews the C-suite and gets to ask them about their cultural problems. And then write up a report with ideas and suggestions. This was very cool. I did write a few adverts. But mostly I wrote internal documents. Most writing is like this: it exists inside institutions and is uninteresting to those outside. But it convinces: it persuades.

Still, I thought of myself as a writer. I had spent years reading books of grammar and style,—not to mention all the actual books I was reading,—and practising the techniques I learned in my emails, memos, reports, and so on. A good writer is not bound by mode or medium. “I would write ads for deodorants or labels for ketchup bottles, if I had to,” John Updike once said. My hero, Samuel Johnson, wrote adverts, too, as well as sermons, and anything else he needed to.

Because of this catholic approach, I was not happy doing only one sort of writing. Like, yes, everyone wants to be a historically famous novelist, but really, the challenge is to write lots of different things and to write them well. And in that sense, I began to think of myself as a late bloomer.

And so the idea was forming, even though I was only writing about it indirectly and behind opaque organisational walls.

Three lessons from my meandering career

Here are some of the things I got radicalised about as I wandered through education, politics, and the law. (Did I mention I went to law school? Not a good idea,—but it is at least useful when I need to write a legal letter.) These three ideas are all foundational to my work on late bloomers.

Everyone has potential.

Whoever you are, you have something in you, some talent, some worth, that cannot be degraded. We can all do something. Those children who failed their exams were a remarkable bunch and made some serious progress. The kids who didn’t know English history made leaps and bounds. To this day, it really boils my piss to think about the utterly lame teaching some of them had received.

So the first lesson is that everyone has potential and if you expect more from people, they will often deliver it. It might not be easy. They might turn out to be idle or bored or whatever. You might be the problem! But there’s often some kind of margin available by expecting more.

Aspiration matters

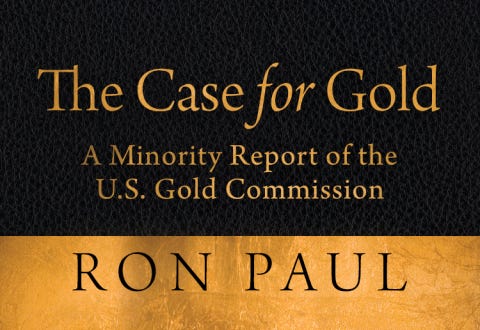

Reading Ron Paul’s minority report on the gold standard on the way to work was a quake moment. Not because I actually think we ought to revert to the gold standard, but because I realised you can continually expose yourself to strange new ideas outside of education. In my twenties, I got up early to learn economics and read history before work. I have notebooks full of supply and demand curves and shelves of the books I read to paper over what I considered woeful gaps in my knowledge. And I read a lot of biography.

So the second lesson is that your ambition might not be fulfilled very early. That is a reason to do more. Before I started blogging, I was writing at home in the evenings, on and off, for years.

The ideas you believe change who you become

I only found a way of expressing that idea recently, when I spent some time re-immersed in John Stuart Mill. Gradually, my interests in literature and history converged with my work in talent attraction. The question, what makes this organisation interesting to the people they want to attract? was introduced to me by an excellent boss. But it represents an idea that goes back to Aristotle. I was, and am, fascinated by advertising because I had previously read Aristotle’s Rhetoric when I wanted to be a speechwriter.

So the third lesson is that you really are the hero of your own life, but not in the sub-Hollywood bullshit way. Your life is a moral journey and the ideas you believe will change where you end up. By not having a notion or model of late bloomers, most people are simply unable to know when they encounter them.

My book is going to provide some of those models, but combine them with what we know from social science to try and explain what we can learn from them.

It was only chemo

Then I got cancer. Not scary cancer. Just pain-in-the-arse, drag yourself around like you turned ninety overnight, cancer. This matters not because I had some life-changing revelation on chemo (apparently some people do, and good for them) but because it gave me four months off work. A lot of that time was spent in a fog. But a lot of it was spent in a book.

One of the things I did was to re-read Penelope Fitzgerald, along with the Hermione Lee biography and the letters and essays. Fitzgerald is one of my favourite novelists. And of course, she was a late bloomer. I then heard Tyler Cowen talking about “people who haven’t done something yet but maybe they will” and the idea started to come together in my blogging and my marketing work.

For a long time, I had been interested in biography and taking time off work also prompted me to do an MA in Biography at Buckingham with Jane Ridley. This course was disappointing in some ways, but the flame was lit. I couldn’t have been happier scraping around in archives and writing to people to discover the secrets of my subject, Elizabeth Jenkins. Elizabeth was a late bloomer in the sense that without the affair she conducted in her middle-forties—the end of which was utterly crushing—she probably wouldn’t have written her most successful novel and biography.

I had planned to write about late bloomers on that course, but there were already books on the topic. But the more I read, the more I believed that what exists on this topic isn’t good enough. We don’t actually understand late bloomers yet. I wanted to write something that would contribute to that better understanding.

So I decided to quit my job and get on with the late bloomer project. Time was running out! I have often been teased for being older than my years. From my perspective, most people cling hopelessly to the vanity of being young and let their age creep up on them. Having children brings into sharp focus the fact that time really does go too fast and that you are going to die sooner than you want to.

If I was going to be a late bloomer, I needed to get on with it. “He that runs against Time, has an antagonist not subject to casualties,” as Samuel Johnson said.

There are no easy answers

At work, I was more and more convinced that talent was being left on the table. And the more I learned about the most accomplished people, the more I saw that their success was often unpredictable. It took the Pope to persuade Michelangelo to become an architect. (Good thing the recruiters didn’t get hold of that one, eh? “Yes, Mr. Michelangelo, you’re a very good painter. But we’re looking for someone with architecture experience, preferably in era-defining, classically-inspired monumental cathedrals.”)

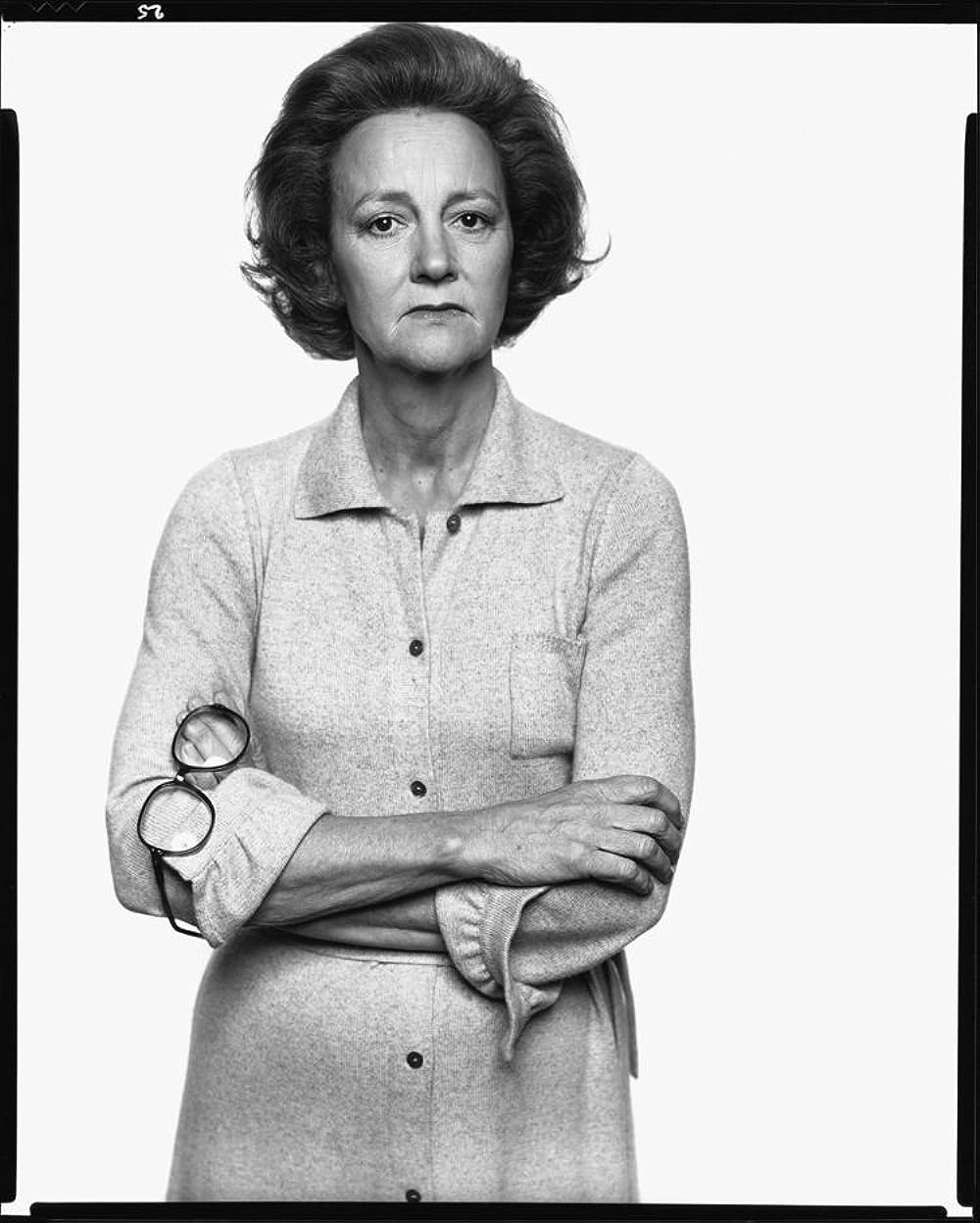

It took the death of her husband and father to start Penelope Fitzgerald writing novels. Before she was elected as Leader of the Opposition, Margaret Thatcher was dismissed by her own supporters and was fifty-to-one against at Ladbrokes. Even when she won in 1979, no-one imagined she would become a globally important politician.

And I had seen this among the children I taught. I had seen it at work, when CEOs dismissed someone’s potential as a future leader because “they’re not an extrovert” or some similar nonsense. All around us, I began to think, there is talent going unnoticed, undeveloped.

Now, this is not a call for easy optimism. You are not going to wake up one day and discover out of nowhere that you could become the next Toni Morrison. There’s no easy answer. Popular ideas like grit have been incredibly unhelpful because they disguise the fact that passionate persistence is only one small piece of the puzzle. A meta-study found that grit seems most useful when we talk about narrow fields like chess or military training. In messier endeavours, which are harder to define, like Einstein’s search for the mathematics of relativity, grit just isn’t as useful.

In fact, if Einstein had merely persisted without changing tack under the influence of other mathematicians, he would have failed. Sometimes quit beats grit. Contrary to Angela Duckworth’s claim that grit can be more important than talent, grit alone cannot see you through any endeavour. It’s likely true that we can all do better at maths in school with more perseverance, but most of us cannot use grit alone to become musicians or gymnasts. Aptitude is required to get beyond a certain level.1

Ideas like grit,—or that other last ditch of no-hope, growth-mindset,—take hold in recruitment, as they do in schools, and their damage spreads like wildfire. What became more totemic to me is a review of a hundred years of findings in psychological research that examined the effectiveness of dozens of different recruitment practices and summarises the best of our knowledge about how to spot talent. This is no slam-dunk either, but it’s some of the best knowledge in this area.

The main lesson I take from this paper is that there are no rules. You cannot just stack deliberate practice, grit, and growth-mindset and journal your way into doing something excellent. The great failing of “smart thinking” non-fiction in the last few years has been to pretend that we can find clean, simple answers, grand ideas that simply need to be applied to our lives.

The reality is much messier, requires more nuanced judgement, and won’t be so easy to define.

What we know about predicting job performance

Let’s get into the details of that paper and what we know about predicting people’s job performance.

The best indicator we have of job performance is intelligence, which the researchers call General Mental Ability (GMA). A smart person can learn their job quickly and thus perform it better. But GMA is not a perfect predictor. There is more variation in employee performance in professional roles than other types of role. The better workers in unskilled jobs produce about 19% more than the average worker; in professional jobs it is 48% more.2

GMA predicts two-thirds of what we would be able to predict if we had a perfect way of measuring talent. The only way to improve on this is to add an integrity test to the GMA test.

However, we do not have a perfect way of measuring talent. And many of the best CEOs are nowhere near being the smartest people. Character matters. There is a lot of value in not hiring people who are brilliant but disruptive or dishonest. But character is hard to measure.3

The lowest scoring measures were self-reported personality traits, graphology, and age. Age has a predictive validity score of zero. Still, it’s a major unspoken factor in recruitment. For comparison, it’s less useful than graphology, which is about as scientifically valid as astrology. Paying attention to a candidate’s age is, according to this research, as irrational as reading their horoscope. Another widely used method in recruitment is to ask for people with a certain number of years of experience. This predicts a mere 16% of the performance you would predict with a perfect measure. And yet it is an impenetrable barrier to most jobs.4

It’s just not that easy to find good talent.

Ok so it’s complicated…

Finding talent is not as simple as running GMA and integrity tests. These are merely the most effective ways we have of predicting performance. They are not a substitute for judgement. Take the example of Katharine Graham. How many organisations would have hired her? She was an outstanding CEO who took the business from revenue of tens of millions to over a billion dollars, who approved both the Pentagon Papers and Watergate publication, and who was the reason Warren Buffet invested in the Washington Post Company.

It is hard to see how someone in her position, with no experience, no track record, who actively disliked the business side of things, and without any discernible qualifications, would have been recruited into her role. Nor is it clear that a GMA test and integrity test would have secured her the position. She had to be known, as a person, and that took time, effort, error, and experience.

Which is why few people did in fact predict her success. Though some came closer than they realised. Anyone who had been paying attention could have seen that she lingered in the room where the men talked politics, that her father rated her despite not promoting her, and that she had outstanding integrity—but it would take some imagination and judgement to have thought of her like that in a corporate context.

Similarly so many people around Margaret Thatcher missed her ability: because she was a woman, because she was irritating, because she was right-wing. But it was more obvious than it seemed that she was smart, had good integrity, and was hugely capable of learning on the job.

We see this again and again with late bloomers. That’s why people become second bloomers, like Steve Jobs and Vera Wang, even though no-one predicts it. Their talents are right there, but they are overlooked because of expertise-blinkers. Jobs was a marketing and computer guy, not an animated film expert. Being a near Olympic skater (as Vera Wang was) doesn’t seemingly have much to do with designing dresses. But once someone has shown you their talent, it is foolish to start quibbling it. And of course skaters have to wear impeccably tailored outfits.

You cannot simply run a GMA and integrity test and hire people based on the results, without meeting them. Talent spotting is a combination of clean measures and messy judgements.

Theories and lives

That’s why my book combines biography and social science. My proposition is that talent is less predictable than we think and that potential exists in the second half of life just as much as it does in teenagers and twenty-somethings. At the moment, this idea is often overlooked or thought to be wrong. My aim is to shift the needle from indifference or disagreement to perhaps. I want to do that by using social science to explain a series of inspiring examples of real people’s lives—a set of late-blooming heroes. Biography never explains, and social science never gives us the thick, messy context of real life. By bringing together these two things—inspiring you with examples and then explaining them with empirical research—I hope to show that sometimes we just cannot see the talent that’s right in front of us.

Who knows how many late bloomers might be out there, waiting for their chance… Whether you are a potential late bloomer, an executive or recruiter, a talent spotter, a friend or spouse who thinks they might know a late bloomer, I want this book to make you curious about the people around you,—about the people who haven’t succeeded yet, but who might…

Thank you for reading The Common Reader. If you want to stay up to date about my book project, read interesting essays about history, literature, talent, and biography, then subscribe for free today.

And we should be careful about how much difference we think grit can make. Duckworth studied cadets at a military academy: her results suggest, according to the meta-study, that grit increased someone’s chance of completing the course by 2.6%. That’s not zero and if you can get that advantage you should take it. But the idea that we can become who we want to be through the inspiring power of passionate perseverance is misleading.

GMA has the highest predictive validity score and is the easiest thing to measure. Give someone an intelligence test and you pretty much know how smart they are. GMA validity varies from .74 for professional and managerial jobs down to .39 for unskilled jobs. That means it is highly predictive of performance in professional jobs but only mildly predictive in unskilled work. For jobs of medium complexity (about two-thirds of jobs in the American economy) the predictive score is 0.66.

Many methods used by recruiters to try and assess this side of things, like Situational Judgement Tests, score quite badly, largely because they correlate strongly with GMA. According to this research, there isn’t very much a Situational Judgement Test can tell you that someone’s general level of intelligence cannot. The same is true of Assessment Centers, Work Sample Tests, and Job Knowledge Tests.

Surprisingly, and contrary to all current advice, structured and unstructured job interviews have the same predictive validity. That is, whether you ask a series of set questions or have a more free-wheeling conversation, you get the same predictive validity of job performance. New and more accurate methods of measuring interview performance has changed the standard view that structured interviews are better predictors of job success than unstructured. When paired with a GMA test, structured interviews increase predictive validity by 18% and unstructured by 13%. Unstructured interviews though are better at predicting someone’s performance in a job training programme.

Years of experience tells you nothing about quality of experience. Some people learn more in one year than others learn in several years. Years of education is similarly not very useful. Much more useful are peer ratings, which score 0.49 (i.e. they tell you about half of what a perfect assessment could tell you). The problem of course is that you cannot use peer ratings to hire someone.

Perhaps if you were looking for talent not in an ordinary recruitment context—an investor, a teacher, a talent scout—you might be able to get peer ratings? But it is difficult. Similarly, conducting a good unstructured interview and giving someone a GMA test is difficult. People don’t like being given an IQ test, nor is it popular to go through an interview process for which you cannot prepare. This is perhaps why so many organisations don’t use what are the best methods.

We should also note that we don’t always know why these things do and don’t work. Employment interviews probably measure a combination of GMA, personality, experience, skills, and behaviour. But we can’t demonstrate that.

This is my favourite idea ever, selfishly so...

Great book idea. Another name to add to your list is Colnel Sanders. He founded KFC after turning 60.

Working in a corporate environment I also think theres alot of ass covering. If you hire someone and they don't turn out, atleast their resume looks good.