What made the Inklings a significant literary group?

Tolkien and Bilbo were both late bloomers

Second Act and Shakespeare

Second Act has had a wonderful start. Tyler Cowen said it is, “One of the very best books written on talent.” Thank you Tyler! And many, many thanks to all of you who have bought a copy. Please do leave reviews and ratings (good or bad!) on Amazon, Goodreads, and elsewhere—as well as helping me, it helps other people to find out about the book.

For American readers, it turns out you can get it in the USA, on Kindle (where it was the #1 New Release in the Entrepreneurship category.)

For those who want to know more, TONIGHT Monday, 13th May, I will be talking online at Interintellect to Thomas Arnold about Second Act.

And the next Shakespeare bookclub is now **19th May**—it was pointed out that 12th is Mothers’ Day in the USA… sorry! You can find all the other Shakespeare posts here.

Why were the Inklings a significant literary group?

Three crucial factors

C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien and others used to meet in Oxford and discuss their work. During this period, Lewis wrote Narnia and Tolkien wrote much of Lord of the Rings. So what made this group—called The Inklings—matter? Three things stood out to me in The Inklings by Humphrey Carpenter.

Tolkien’s marriage was in a difficult patch when he became friends with Lewis, and he felt that Lewis compensated for his loneliness at home.

None of the Inklings was called away to war work of any sort.

Although they only “encouraged” rather than “inspired” each other’s work, that mattered a lot for Tolkien, who had to be pushed to re-start Lord of the Rings when he was halfway through.

More than anything else, these seem to have been the important factors, other than C.S. Lewis’s personality.

A turning point in his career

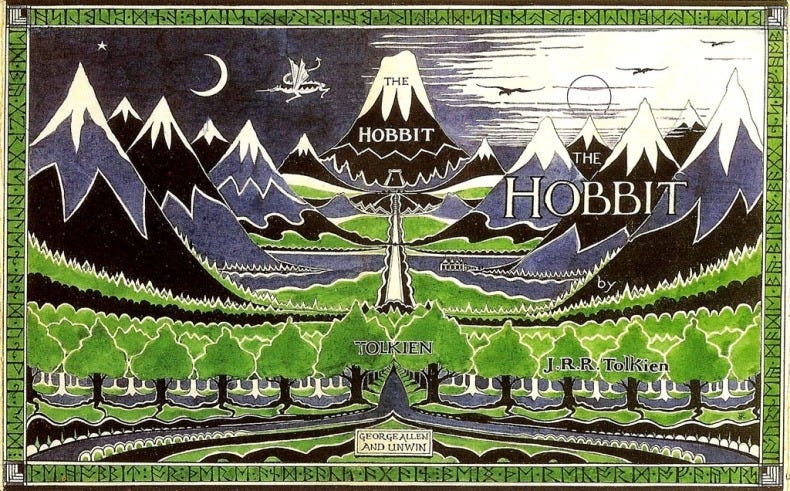

You can think of Tolkien, and Bilbo Baggins, as late bloomers. Before Gandalf sends him on his adventure, Bilbo is a quiet, respectable hobbit, the sort of person who draws no gossipy attention in his neighbourhood. So important does Bilbo think this respectability is, that he believes himself incapable of adventure. But Gandalf knows Bilbo has hidden capacities, inherited from his fairy-like mother. So off Bilbo goes, with thirteen dwarfs, and finds himself not just tolerating discomfort while climbing mountains, but escaping from danger, dealing with trolls, and discovering a magic ring, which Tolkien calls a “turning point in his career.”

This is the classic paradigm of late blooming. Some turning point, some switch, must be reached. Without the ring, Bilbo would have gone on an adventure, and developed new self-esteem by getting out of his comfort zone. But with the ring, he goes far beyond this, putting himself in harm’s way to save his friends, to win fights, and to face dragons. Once he knows he can become invisible, Bilbo is able to take new risks and discover ever more of his abilities. As Emerson said, “With the exercise of self-trust, new powers shall appear.”

When Bilbo picked up that ring, more than one career reached an unnoticed turning point. Tolkien was almost middle-aged when he wrote The Hobbit, going from someone who devised languages and legends in his spare time, to a popular children’s author. It was never meant to be published, being instead a book for Tolkien’s own children. He had been working on his cycle of myths and languages, now know as The Silmarillion and The History of Middle Earth. But The Hobbit was a new departure, and since it wasn’t written with publishing in mind, you might say that he wrote it under the power of invisibility. Unlike his academic work and reputation, and his intentions for The Silmarillion, this wasn’t meant to be seen.

Fiction didn’t come naturally to Tolkien. He spent over a decade working on The Lord of the Rings, and required large encouragement from C.S. Lewis. He started as a professor of philology, translating Sir Gawain and studying Beowulf, and became the best-selling author of anti-modernist literature. Everything he had done before was preparation for his epic novel, he just hadn’t planned it that way. With the exercise of self-trust new powers had appeared.

If you feel that way about Keats!

I particularly enjoyed reading that Lewis once bellowed after a student, “You needn’t come here again if you feel that way about Keats”, and challenged another to a sword fight upon reaching an irresolvable disagreement about the value of Sohrab and Rustum. Lewis had two swords in his office and nicked the student, drawing blood. So many literary biographies are long and ponderous but this one is well-paced, absorbing, and full of character. I am by no means a Lewis acolyte, but I thoroughly, thoroughly enjoyed this book.

I've been working on a book retracing the walks Lewis and the Inklings took between the wars...it involves lots of pubs and thinking about how and why we romanticise England. The Tolkien and Lewis relationship didn't work so well when they were walking. 'Tollers' would keep on stopping to peer at a plant or road sign, while 'Jack' would stomp on at a 'ruthless' place. Very like their writing habits: once he had an idea for a book, Lewis would charge ahead and get it done in weeks. Tolkien, as you say, took decades.

This might sound trivially obvious, but one reason why the Inklings were important is that they essentially created the modern fantasy genre, both through their fiction and through the popularization of the term mythopoeia and the concept of "worldbuilding" in their criticism.

Seventy or so years later, I think it's clear that that had a profound impact on the world of books and -- via influences on tabletop RPGs, video games and cinema -- on pop culture in general.