Will AI create a new creative renaissance?

Maybe, but lots of other factors matter too

In his recent interview with Chris Best, the venture capitalist Marc Andreessen predicted that AI would lead to a creative renaissance. Here are his (abridged) remarks.

… anybody who’s a creative in any professional field all of a sudden has a new superpower… every screenwriter is going to be able to render their own movies.

… And so I think this technology could lead to a creative renaissance that is just absolutely spectacular.

… you’ll be able to have a single person who can bring into the world something that would have been like a billion dollar projects or impossible five years ago.

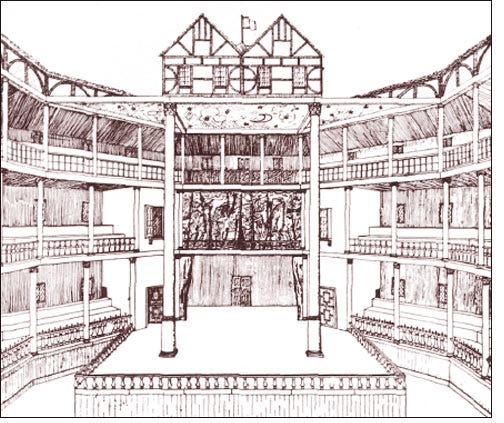

It seems to me obvious that significant advancements in art are often spurred by new technology: perspective and the Renaissance, indoor theatre and the Elizabethan drama (Shakespeare!), mass circulation and the nineteenth century novel, celluloid and Hollywood. Shakespeare became Shakespeare partly because he lived at a time when new technology gave him a first-mover advantage; similarly with Dickens and the popular novel—it was the financial crash of 1825 that led to the rise of cheap, serialised media, just in time for Pickwick. New technology so often leads to new art.

But this is not all that it takes. Romanticism was not the result of technology: it was birthed by ideas, being hugely interested in the new methods and findings of science and the revolution in philosophy brought about by Hume and Kant, as well as becoming politically revolutionary especially after 1789. The great period of music from Bach to Beethoven was partly the result of new instruments, but partly the result of new freedoms: Mozart was liberated from patronage and invented the piano concerto. (Beethoven had patrons but was also full of revolutionary ideas.) Similarly, poets like Milton are the result of a change in ideas, more than a change in technology. Modernism similarly, across the arts, was a new way of thinking about the world—a response to changes in society—more than a technological shift. Stravinsky was an innovation of the spirit.

And some technologies fail to deliver great art. Television has not yet done anything on the level of classical music, the nineteenth century novel or Hollywood. Breaking Bad and The Sopranos were very popular (and shows like them have become the main cultural recreation of educated people, alas) but the idea that these works have the same depth of aesthetic value as George Eliot or Alfred Hitchcock is merely the self-reassurance of a society that has become comfortable in its own mediocrity. They might have brought television to new heights of accomplishment, but they are imitative of the movies, over-long, and often with cliched dialogue. There is no FirstFolio of HBO.

Similarly, and importantly for this question of a creative AI renaissance, the internet has yet to produce any new form of art. Mediums have been suggested, such as video games, but nothing has yet emerged that can hold a relationship to our society that Tolstoy and Flaubert held to theirs. As with television, the moral content of this art is too thin, and the aesthetic criteria too weak. The problem is not that these modes are too commercial, but that their aim is mere entertainment. No significant truths are told. That doesn’t mean they aren’t very well-accomplished, but they cannot speak to our times in the manner of Jane Austen, nor can they relate what it is like to experience life as Proust did. There is no Dante, no Michelangelo, no Schubert of our age.

To get a period of great flourishing, then, you need more than technology. Shakespeare had a combination of: elite overproduction (high quality audiences), indoor theatre (a profound break with the past), economic and political expansion (new ideas, new influences, a vibrant culture, wealth), changing morality (church struggles and the puritan tensions), as well as a vibrant theatre culture which drew strongly on the vibrant poetry culture. Shakespeare was very much the product of his times, which were hugely multi-faceted.

You see this again and again: many of those factors are present in the other examples I gave. Think of Dickens who had: newly literate audiences hungry for written entertainment to read aloud at home, serialisation, economic expansion, globalisation, the industrial revolution, huge political transformations and discontents, and changing morality. This sort of combination of factors comes up again and again. What matters is getting the right technology for the times. It in the intersection of all of these factors that creates the true renaissance because it births a form of art that is well-matched to the conditions of the time—be they aesthetic, cultural, political, moral, or, most likely, some combination.1

Finally, creative renaissances come from the past. The Renaissance was, literally, the re-birth of ancient ideas, the rediscovery of classical art. Those ancient ideas were put to magnificently new uses, not least by Michelangelo who invented Mannerism. This influence blossomed into the classical style, which may not be entirely classical, but was unthinkable without the deep influence of Greece and Rome. The same is true of the neo-Gothic movement of the nineteenth century, which was much more neo than gothic, but which was unthinkable without a deep re-immersion into genuine medievalism.

The history of art is the history of such responses to the past. Dante and Virgil. Milton and the great epics. T.S. Eliot and Dante (and everything else…). Shakespeare and Ovid. Keats and Spenser. Modern influences matter hugely too: Scorsese and Hitchcock, the Rolling Stones and blues guitar; this is the same as Shakespeare and Sidney, Tennyson and Keats. Each generation has to make the work of the previous generation anew.

It may be that what the internet has allowed us to do is to explore old art more deeply. It may be that we are trapped into a continual entertainment of recent mediocrity rather than a genuine absorption into classic works (lots of streaming movies from the last twenty years, but little attention for F. W. Murnau), but there may be a sense in which new technology has produced cultural stagnation because we are busily involved with works from the past, in a period of preparation for the new.

This might go two ways. Either the internet is giving us the access to explore backlists and AI will thus enable a flourishing, or, the next generation of artists will not be very online at all. While half the world gazes at re-runs of The West Wing, the true artists of the new Renaissance may be at the library or in the movie theatre watching re-runs on 35mm.

So whether AI brings us a creative revolution or not (I hope it does) depends on far more than just the technology. Indeed that one large question I posed earlier hangs over the possibility of an AI creative renaissance. Where is the great art of the internet? Why didn’t that accomplishing anything on the scale of Bach, Shakespeare, or Dickens? Our times are calling out for great new art! Yet none appears. Periods of stagnation are quite normal (there were great lulls before Modernism and Romanticism). The question is whether AI can solve this conundrum. If so, it will do so in unexpected ways. Renaissances are fresh. Contra Marc Andreessen’s example of the screenwriter, if a renaissance is got underway by AI it will likely be in a mode of art we haven’t really thought about yet.

If a new creative era does arise, we’ll know it partly by its distinct unfamiliarity. If it is wonderful, it will be strange.

Too often, modern mediums are made like collage. Mad Men has the moral perspective of a smug liberal (can you believe how sexist the sixties were—and all that smoking!) with the visual style of Wong Kar Wei and the narrative arc of Hollywood’s beloved five-act structure, so that it feels like a standard sit-com/drama/serial structure that’s been bloated with immaculate sets and vintage clothing. In the 1590s, Shakespeare made a whole drama with minimal visual aids. At times it feels like modern art forms only care about their visual style, as if everything was a billboard or magazine cover brought to life.

But the collage can never be a true mode of art. Some principles of aesthetics or morality have to hold the whole thing together. This is not to say there must be rules: what rules did Shakespeare follow? Nor am I arguing for “unity”, the dreaded bogeyman of aesthetics ever since Aristotle, as if a play like The Winter’s Tale can never succeed because it juxtaposes opposing modes. Many collage-type works of art have succeeded: Tristram Shandy and Matisse to name but two.

In those cases, the collage was the means of making a moral, political, philosophical, or aesthetic point. In our time, collage is the default mode for creative industries who are more concerned with either meeting genre requirements or subverting them or working “cross genre” than with the actual substance of the work. So many of the best accomplishments of modern culture, like Studio Ghibli, are incapable of being well described by genre labels. Many of the modern novels that have retained profound followings—books like Mating or Pachinko—are not simple to classify. Until we reunite style with a sense of moral purpose, I expect the collage to continue to predominate and to win the easy praise that always accrues to collections of enjoyable things.

I think the thrust of this is partly right: technology without ideas results in vapid churn. But that's true of a pencil - and is a truism.

AI will produce exponential amounts of dismal art like the jejune imagery and cruddy writing that pops up all over the place now.

But if it helps mine inspiration and prompt lateral thinking in the mind of an artist, it could be a very good pencil indeed.

On TV, I think The Wire cleared the high bar you set pretty comfortably.

And controversially, I don't think The Stones ever did - they scraped more authentic writers and musicians for saleable 'content' in a way that reminds me of... AI.

(Sorry to Rolling Stones fans for making you splutter on your morning coffee!)

'...a society that has become comfortable in its own mediocrity..' So on point. Great essay.