With a penny-piece on each eye, and his wooden leg under his left arm

Martin Chuzzlewit and Lex Fridman

Martin Chuzzlewit is under rated

I do not make New Year’s resolutions, but I am hoping to participate more in the Dickens Chronological Reading Club this year. It is superbly well organised by Rachel and Boze, who produce informative supporting blogs for each book, and there are Zoom calls to discuss each novel. I had not, to my shame, read Martin Chuzzlewit before, and am glad to have done so as part of this group. All the best Dickens is still to come on the reading schedule—Bleak House, Little Dorrit, and Great Expectations, three high points of the nineteenth century novel. You can find the schedule here. We even have short Dickens novels coming up: Hard Times and A Tale of Two Cities.

Martin Chuzzlewit is a somewhat unloved Dickens novel. It is known for its American section, which is terrible. Many of the other sections, though uneven, contain some of Dickens’ best writing and one of his best characters. Let’s start with America…

Wanting to expose selfishness and hypocrisy, Dickens mocked American speech and grammar patterns to make them look stupid. This is part of a long tradition of Europeans believing Americans lack culture, tradition, class, and gentility. Many writers have condescended to Americans like this. (British people still sometimes joke about the “stupid” way Americans speak, and do so with as little nuance as Dickens.) To make his point, Dickens uses what Linda M. Lewis calls overblown analogies and “unglittering generalities.” This bluntness was obvious at the time. Emerson said:

He has picked up and noted with eagerness each odd local phrase that he met with, and, when he had a story to relate, has joined them together, so that the result is the broadest caricature; and the scene might as truly have been laid in Wales or in England as in the States

Dickens later defended himself saying he was not trying to give a picture of the whole nation, just to satirise one aspect. The problem is not with his being a satirist: the problem is with him being a bad satirist. His rhetoric is equal to the low-quality rhetoric of his characters. It reads more like a bar-stool rant than a sophisticated satire. Dickens knew this. He wrote to Jane Carlyle,

I am quite serious when I say that it is impossible, following them [the Americans] in their own direction, to caricature that people. I lay down my pen in despair sometimes when I read what I have done, and find how it halts behind my own recollection.

He was hugely frustrated by his visit to America, unable to move with all the attention he received. He was hounded, day and night, in person and by letter. People even wanted to get cuttings of his hair from the barber. No wonder he despised it. His hatred blunts the novel. Harry Stone has shown that many of the experiences he writes about in letters made it into the journalistic book American Notes. Much of the material also informed Martin Chuzzlewit—but not the positives. He purposefully made unrepresentative selections when he wrote about America in Chuzzlewit. Stone attributes this exaggeration and intense focus on the negative as the result of an “emotionally conditioned” memory. That force often drives Dickens’ work, for better or for worse.

Maybe that is why this novel has often been unloved. The problem started early on, with poor sales for the first two monthly instalments. They are thought to be dull. I didn’t find them so, but it is true that all the best material—and there is a lot of it—comes later. Chuzzlewit also often lacks the content that had popular appeal. Albert Guerard said, “For nine of its nineteen months Chuzzlewit offered little happiness and little moral goodness, and few glimpses of feminine purity and innocence.” But to modern readers the feminine purity that comes later in Ruth is weird and creepy and bloody dull. And that moral goodness seems flat and insipid. I love this book for its villains. Dickens is at his best writing about dark and twisted hearts, and there are plenty of them. Chapter nineteen has everything I think of as first-rate Dickens. It is hilarious, full of dark and light, making dark humour out of death. As Guerard says, though, this chapter may well have been repulsive to many Victorian readers. It is a novel that will never entirely please its readers.

Here is a description of Sarah Gamp from that chapter, one of the greatest characters in all of Dickens work (the phrase “lying-in or a laying-out” means a birth or a death):

She was a fat old woman, this Mrs Gamp, with a husky voice and a moist eye, which she had a remarkable power of turning up, and only showing the white of it. Having very little neck, it cost her some trouble to look over herself, if one may say so, at those to whom she talked. She wore a very rusty black gown, rather the worse for snuff, and a shawl and bonnet to correspond. In these dilapidated articles of dress she had, on principle, arrayed herself, time out of mind, on such occasions as the present; for this at once expressed a decent amount of veneration for the deceased, and invited the next of kin to present her with a fresher suit of weeds; an appeal so frequently successful, that the very fetch and ghost of Mrs. Gamp, bonnet and all, might be seen hanging up, any hour in the day, in at least a dozen of the second-hand clothes shops about Holborn. The face of Mrs. Gamp — the nose in particular — was somewhat red and swollen, and it was difficult to enjoy her society without becoming conscious of a smell of spirits. Like most persons who have attained to great eminence in their profession, she took to hers very kindly; insomuch that, setting aside her natural predilections as a woman, she went to a lying-in or a laying-out with equal zest and relish.

Here is an example of the contrasting quality in the different sections of Martin Chuzzlewit. Whereas many of the American characters lack idiom, Sarah Gamp never says anything any other character could say. Her speech is utterly unique to her. Here she is describing the day her husband died.

“Ah!” repeated Mrs Gamp; for it was always a safe sentiment in cases of mourning. “Ah dear! When Gamp was summoned to his long home, and I see him a-lying in Guy’s Hospital with a penny-piece on each eye, and his wooden leg under his left arm, I thought I should have fainted away. But I bore up.”

Dickens may have lost the popular imagination by becoming less sentimental in Martin Chuzzlewit, but he was exercising the faculties that would come to such great use in the great novels of the 1850s.

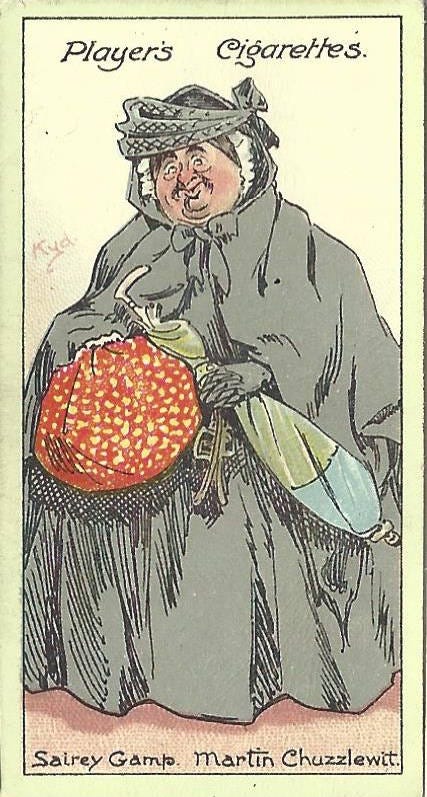

And the sentimental sections are quite poor. Indeed, the more virtuous the book gets the more boring it is. I could have skipped the ending altogether. Sometimes the public is wrong! (He made the same mistake with the new ending of Great Expectations.) This novel is essentially comic and the comedy comes from villainy and disorder, from discord and confusion, not from pretty little Ruth or Tom Pinch, loveable model of virtue though he is. Dickens thought Tom was the heart of the novel, giving him the frontispiece illustration and the abominable final page. No! No, no, no. Give me Sarah Gamp and her terrible ways. She is the one who survived in the public imagination, who inspired other novelists, and who was put on a cigarette card. She is the work of genius here, not Tom. Dickens was often an idle hypocrite when he was sentimental and a genius when he wrote about the dark corners of life. All the weaknesses are driven by the morals. The plot is too thin and far too incredible—but only when the characters are doing good. During times of misdeed this book hums along for page after page as if it were a newly built machine.

Martin Chuzzlewit is also criticised for having too many coincidences. Adam Grener defends the use of coincidence as a technique that highlights the growing tension between community and individualism at the time. That’s true. But there are simply too many of these chance encounters. At times it feels like a roll call of characters, like you get in the season finale of a television programme. Perhaps chance encounters were more common when London was only a city of two million people. Anyone who lives in London today knows you do have strange chance meetings somewhat frequently. But it happens chapter after chapter and feels hackneyed. And all in the service of a moral lesson that gets over delivered anyway.

Dickens’ best work is entertainment, not sermonising. And this novel is full of splendid physical comedy, which works best when it has a dark undertone, such as this passage:

…the general, attired in full uniform for a ball, came darting in with such precipitancy that, hitching his boot in the carpet, and getting his sword between his legs, he came down headlong, and presented a curious little bald place on the crown of his head to the eyes of the astonished company. Nor was this the worst of it; for being rather corpulent and very tight, the general being down, could not get up again, but lay there writhing and doing such things with his boots, as there is no other instance of in military history.

Of course there was an immediate rush to his assistance; and the general was promptly raised. But his uniform was so fearfully and wonderfully made, that he came up stiff and without a bend in him like a dead Clown…

That is in the otherwise tedious American section, proof that Dickens should have stuck to his knitting. Note the mention of death that slips into this passage like the ghost that passes through the passage about Sarah Gamp above. Words like murder, slaughter, ghost, and corpse are everywhere in this book—and your expectations won’t be disappointed…

This might be Dickens’ most uneven book. It swings from comic opera to soap opera. In London, it is a book of genius; in America it is imbecilic. Thankfully America doesn’t occupy too many chapters. It would have been improved by being much shorter. No wonder he abandoned the episodic approach and started to plan his novels from here onwards.

You must read it though: if you don’t, you will miss out on some of the best of Dickens. Until you know Mrs Gamp, you do not know his true capacity for character.

Lex Fridman’s Reading List

Podcaster Lex Fridman posted his 2023 reading list to Twitter and has been widely mocked for it. There are two criticisms. Some people think it’s a list of books he ought to have read in school. Others say it’s too simplistic a list for someone who holds themselves out as a public techie intellectual. I can’t comment on the sci-fi because I have never read sci-fi, other than some Wells and similar. It’s not an appealing genre to me, though I plan to try and fill in some gaps at some point. (Nor have I read Brothers Karamazov, because I found Crime and Punishment so dull. I ought to try again.)

But, to criticise someone for reading a “school-level” list is nuts. Get something better to do with your time! For one thing, he is re-reading some of the books. For another, those books are put on school reading lists for a reason. And reading wears off. The books you read in school don’t stay fresh in your mind forever. If you are proud of having read something a decade ago or more, it’s time to re-read it. Just because a book is on a middle-school syllabus doesn’t make it a middle-school level book, whatever that might mean. Am I supposed to jeer because Orwell is basic? And Hesse? OK…

As for the idea he ought to have read these books already considering his position… To the extent that the list is not re-reads, maybe we can conclude from this that books (or at least these particular books) are less important than we would like them to be. Taleb took it as evidence that Fridman is a fool, but he takes a lot of things as evidence of people being fools.

I for one was glad to see such a common reader project being undertaken. More people should have reading lists like that. And it is a good list! If you liked Fridman’s list and want to broaden it a little I recommend adding The Howling Miller, The Razor’s Edge, Pachinko, Persuasion, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, and The Unwomanly Face of War.

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying The Common Reader, let your interesting friends know what you think. Or leave a comment.

If you don’t subscribe to The Common Reader, but you enjoy reading whatever’s interesting, whenever it was written, sign up now.

Henry,

Thanks much for this (as always) very thoughtful essay on "Chuzzlewit."

I just finished it a bit back, and your "unpacking" of it--its characterizations, its unevenness, and its priming the pump for the best work--really made sense to me.

Three points:

1. ". . . he was exercising the faculties that would come to such great use in the great novels of the 1850s": Truly. Sharpening his pen, if you will.

2. "Give me Sarah Gamp and her terrible ways. She is the one who survived in the public imagination, who inspired other novelists, and who was put on a cigarette card. She is the work of genius here, not Tom.": This seems compelling to me--a character like Gamp is a source of unending (sometimes perverse) merriment. It's hard to have this kind of fun with an earnest character like Tom.

3. "Dickens’ best work is entertainment, not sermonising. And this novel is full of splendid physical comedy, which works best when it has a dark undertone . . . .Until you know Mrs Gamp, you do not know his true capacity for character.": This seems to bear out the adage that a writer does best to show and not tell.

Thanks again, Henry, for this insightful piece that gave me excellent perspective on "Chuzzlewit" in the Dickens canon.

Blessings, wishing you and yours a wonderful 2023!

Daniel

Brothers Karamazov is a far easier-on-the-eye book than Crime and Punishment. Definitely worth the time. Having said that, among Russian novelists I prefer Tolstoy and Gogol (anyone trying to understand the current state of the Russian army would do well to read Dead Souls!).

.