You are a (partial) Utilitarian, whether you realise it or not.

A short defence of a good idea.

With the news that OpenAI was nearly ruined by the actions of a group of Effective Altruists, the scandal of Sam Bankman-Fried covering-up and justifying fraud in the name of Effective Altruism, utilitarianism is once again being described as heartless rationalism, which is potentially evil because it allows the ends to justify the means. When, on top of that, Peter Singer’s Journal of Controversial Ideas published an article about zoophilia, many were confirmed in their view that utilitarianism is a dangerous and naive philosophy. Ted Gioia has even joked that utilitarians might sell their granny to sex-traffickers if they thought it would create “the most happiness for the greatest number.” Effective Altruism failed, this reasoning goes, because of the fundamental flaws of utilitarianism. Maybe, but utilitarianism is bigger than Effective Altruism. It’s an important set of ideas that underpin the modern world.

Here are some of the ideas you might be sympathetic to which have their origins in various forms of utilitarian thinking:

Women should have the vote. The suffrage movement of the 1870s and onwards was largely rooted in the work of philosophers like Mary Wollstonecraft, Jeremy Bentham, and John Stuart Mill and his wife Harriet Taylor. Mill’s speech in Parliament and subsequent book The Subjection of Women are both canonical works of utilitarian thought. Is this the largest increase of welfare in history? Utilitarians weren’t the only ones who accomplished this, but they were crucial to the cause.

The way we treat animals in farms is wrong and we ought to either raise welfare standards significantly or become vegetarians and vegans. I know so many people who have changed their eating habits, either for this reason or because they think it will help mitigate climate change. The reasoning is utilitarian. This is a significant change in social behaviour, in which utilitarian philosophy played a large but often unrecognised role.

Government spending policies should be tested with cost-benefit analysis, to make sure that we are getting good value for money. This seems like common sense, but it took the work of economists and utilitarians to make it so! Indeed, whenever you think about being “cost-effective”, you are essentially being utilitarian.

Government policy should be assessed on its outcomes, not intentions. I would rather know that public health policy is being run by utilitarians than anyone else. When it comes to sanitation, vaccination, and medication the idea of “the greatest good for the greatest number” is the correct one. Same goes for getting more children into good schools, mitigating the effects of climate change, and calculating tax levels. Everyone’s a utilitarian when they are admitted to hospital.

Legal reform so that punishments are effective and humane. Jeremy Bentham analysed the criminal law to see if the bad effects it produced were outweighed by its good effects. In this way, he argued for reform of the harsh and wicked penal code, and influenced the movement to remove the death penalty. No-one now wants to reinstate flogging. Utilitarianism is often present in criminal cases: who lets a violent criminal go free because they have good intentions?

Making charity effective. Large amounts of time has been dedicated making charities work more efficiently. And $1bn has been donated to charities that are most effective. All because of the work of Effective Altruism.

Utilitarianism is often contrasted to virtue ethics, the idea that we should act with good intentions, the claim being that if we only calculate the consequences of our actions without thinking about character or intent, we will justify very bad acts indeed. But this is a false distinction. In Utilitarianism, Mill wrote that desiring virtue was central to utility, and that utilitarian moralists

not only place virtue at the very head of things which are good as a means to the ultimate end, but they also recognize as a psychological fact the possibility of its being, to the individual, a good in itself, without looking to any end beyond it; and hold, that the mind is not in a right state, not in a state conformable to Utility, not in the state most conducive to the general happiness, unless it does love virtue in this manner.

That is, virtue is an essential means to reaching good ends, and it is good for its own sake to be a virtuous person, to cultivate yourself spiritually, emotionally, and practically.

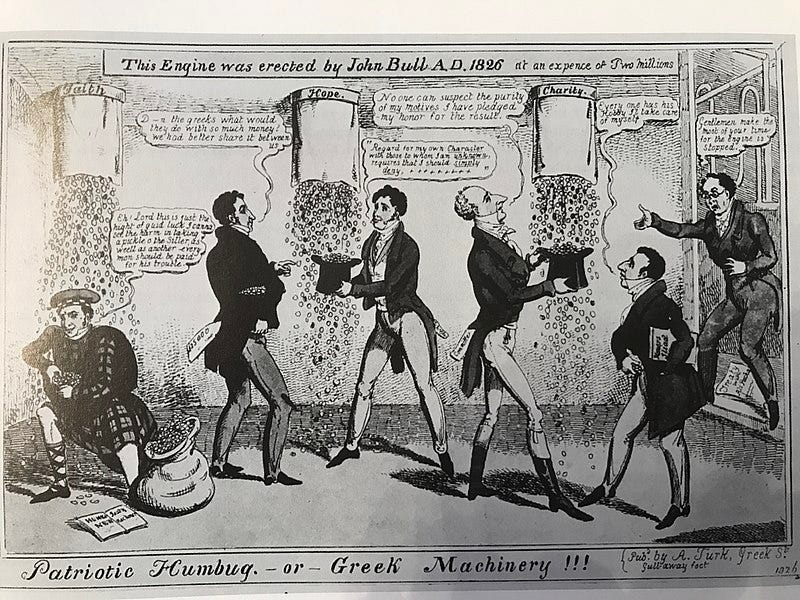

The recent scandals will not be the end of utilitarianism, though it might be the start of a decline in Effective Altruism. Many Benthamites were revealed to have been involved in the speculations and pocket-lining of the 1825 financial crisis, which damaged their reputation for high-mindedness and ethical thinking. But that wasn't the end of Bentham, or utilitarianism. And it isn’t now. Effective Altruism is still a good idea, based on important principles that have changed the world for the better.

This is really helpful. I think people have an aesthetic dislike of utilitarianism more than anything; it’s not actually moral. Everyone is, e.g., at least 90% utilitarian when they shop for groceries.

Utilitarianism has been so influential on the modern world. It is part of what makes the West so great.