I was recently stuck in the bureaucratic malaise of the British Library like a fly on a spider’s web, and so I started noodling around in the catalogue looking at theses written about Jane Austen. “Free Indirect Speech in the Work of Jane Austen” by Hatsuyo Shimazaki immediately caught my eye.

What was there to say for three hundred pages about Free Indirect Speech…?

You all know about Free Indirect Discourse or Free Indirect Style. This is when the thoughts of a character are expressed directly in the narrative, no speech marks, no “he thought” or “she thought”. Here’s a classic example from Pride and Prejudice.

On the following Monday, Mrs. Bennet had the pleasure of receiving her brother and his wife, who came, as usual, to spend the Christmas at Longbourn. Mr. Gardiner was a sensible, gentlemanlike man, greatly superior to his sister, as well by nature as education. The Netherfield ladies would have had difficulty in believing that a man who lived by trade, and within view of his own warehouses, could have been so well-bred and agreeable.

This is a passage of third-person narrative. But the section in bold is clearly the words of Miss Bingley. Austen has slipped Miss Bingley’s thoughts into the main narrative without identifying them with speech marks. She ventriloquises Miss Bingley for ironic effect.

Austen uses this technique all the time. She perfected it. It’s her most important contribution to the development of the novel. She uses it so experimentally in Emma that it is she who deserves all the praise critics usually reserve for Flaubert.

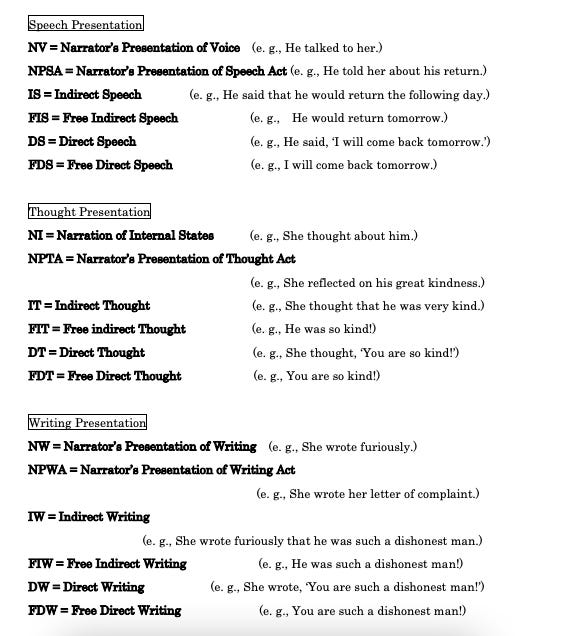

Hatsuyo Shimazaki’s thesis makes a clear distinction between Free Indirect Thought and Free Indirect Speech.1

Usually, we just talk about Free Indirect Discourse, bundling internal thoughts and external speech together. Shimazaki argues that Free Indirect Speech is a distinct and subtle technique.

A passage of FIS [Free Indirect Speech] is a report of someone’s speech perceived objectively by another. By contrast, a passage of FIT [Free Indirect Thought] reveals a character’s subjective view. FIS and FIT arise from different perspectives and work almost in opposite ways. They must therefore be seen as different devices, even though syntactically they share the same stylistic form.

The critic Dorrit Cohn had made this distinction (using different terminology) in her seminal book Transparent Minds but said that Free Indirect Thought (which displays consciousness) was far more interesting. Critics have paid much more attention to Free Indirect Thought than Free Indirect Speech. Shimazaki wants to change that.2 She argues that critics became ideological about the way they examined these issues, and wanted a return to empirical scholarship.3

What follows is a reasonably detailed summary of some of Shimazaki’s main arguments, along with a short example of how the idea applies to Emma (spoilers!).

I found this thesis fascinating and I hope it helps you to read Austen a little differently.

Indirect speech in quotation marks…

Look at this passage from Persuasion.

‘How is Mary looking?’ said Sir Walter, in the height of his good humour. ‘The last time I saw her, she had a red nose, but I hope that may not happen every day.’

‘Oh! no, that must have been quite accidental. In general she has been in very good health, and very good looks since Michaelmas.’

‘If I thought it would not tempt her to go out in sharp winds, and grow coarse, I would send her a new hat and pelisse.’

Anne was considering whether she should venture to suggest that a gown, or a cap, would not be liable to any such misuse, when a knock at the door suspended everything. ‘A knock at the door! and so late! It was ten o’clock. Could it be Mr Elliot? They knew he was to dine in Lansdowne Crescent. It was possible that he might stop in his way home, to ask them how they did. They could think of no one else. Mrs Clay decidedly thought it Mr Elliot’s knock.’ Mrs Clay was right. With all the state which a butler and foot-boy could give, Mr Elliot was ushered into the room.

The bolded section is Free Indirect Speech, but the words are within quotation marks. To begin with we know who is talking, Sir Walter or Anne; but in the bolded section “the characters’ speech is presented as ‘a chorus of voices’”. According to M. B. Parkes, this bolded section “represents both direct and indirect speech as well as statements which could be neither.” Parkes saw this use of quotation marks as experimental, containing as they do an assortment of different sorts of speech and narrative. Most writers don’t put this sort of indirect speech in quotation marks: they only use quotation marks for words characters actually said. By doing this, Shimazaki says, Austen is using a sort of Free Indirect Speech combined with proto-Free Indirect Speech.

And she learned it from the novelists of the eighteenth century, notably Samuel Richardson.

Double-voiced speech

Quotation marks for speech became established in the early- to mid-eighteenth century. This allowed for experiments in the way speech was presented, either within or without such marks. This was also the time when reading silently started to become dominant over reading aloud (though of course there was still a significant reading aloud culture). Punctuation developed to meet the needs of people reading silently.

Speech in Sir Charles Grandison should not be regarded simply as a verbatim record but is presented through typographic experiments, in order for the reader to feel the dialogue more vivid, as if it were spoken out loud.

Clarissa contains many passages where speech is reported in the narrative of a character (i.e. the letters contain other people’s reported speech). As Bakhtin said, as soon as we report other people’s speech ourselves, it takes on another quality. It is not just their speech, but their speech as we report it: it becomes double-voiced allowing for “doubt, indignation, irony, mockery, ridicule, and the like.” See this from one of Clarissa’s letters.

'So handsome a man!—O her beloved Clary!' (for then she was ready to love me dearly, from the overflowings of her good humour on his account!) 'He was but too handsome a man for her!—Were she but as amiable as somebody, there would be a probability of holding his affections!—For he was wild, she heard; very wild, very gay; loved intrigue—but he was young; a man of sense: would see his error, could she but have patience with his faults, if his faults were not cured by marriage!'

What do these italics denote? Clarissa knows that the person whose speech she is reporting is inflected with satire and jealousy. With the speech marks, this effect is enhanced. We get the sense of Clarissa mimicking this person, and making satirical emphasis while doing so. It is not just ventriloquism: it is scornful parody. In Shimazaki’s words: “The heroine reports what another character said about herself and the merged voice sounds satirical, particularly when emphasized with the use of quotation marks.” This is a proto-Free Indirect Speech. (I shan’t recapitulate Shimazaki’s evidence base for the wider claim, but I do recommend the whole chapter of her thesis. It’s compelling. Excitingly, she finds that Rasselas (1759) is the first time modern quotation marks are used, which is when we open and close speech ‘in this manner’ with the ‘he said’ and ‘she said’ left out of the marks.)4

Who are the precursors?

After experiments and proto developments in Richardson, Fielding, and Sterne, Shimazaki finds sustained proto-Free Indirect Speech in Evelina by Fanny Burney. Written in 1778, this novel comes from a time when speech mark usage had become standardised. The passages marked in bold in this quotation are examples.

He begged to know if I was not well? You may easily imagine how much I was embarrassed. I made no answer; but hung my head like a fool, and looked on my fan.

He then, with an air the most respectfully serious, asked if he had been so unhappy as to offend me?

“No, indeed!” cried I; and, in hopes of changing the discourse, and preventing his further inquiries, I desired to know if he had seen the young lady who had been conversing with me?

No;-but would I honour him with any commands to her?

“O, by no means!”

Was there any other person with whom I wished to speak?

I said no, before I knew I had answered at all.

Should he have the pleasure of bringing me any refreshment?

I bowed, almost involuntarily. And away he flew.

Shimazaki says: “By adding a question mark to a passage of IS [indirect speech], the shift is subtly made from the voice of the reporter, Evelina, to the speaker, Lord Orville.” There is awkwardness here though. The line “would I honour him with any commands to her?” must have been spoken originally as “would you honour me”. If the reader is going to keep up, this sort of thing cannot be sustained very far. The fact that novels were read aloud (we know Burney and Richardson read aloud) may be why these techniques are used sporadically: it soon becomes obvious to the reader how entangled this transposition can become.

This matters because Austen can’t have learned Free Indirect Speech from her predecessors as much as she learned Free Indirect Thought from them. It is a standard critical account that the use of Free Indirect Discourse for consciousness pre-dated Austen in Burney, and that Austen developed the technique and took it much further. But Burney only used fully developed Free Indirect Thought; her experiments in Free Indirect Speech were, as we have seen, more limited. Austen “could not have learned about FIS from them, although she could have noted a few instances of proto-FIS (in the third person)”.

Not what happened: how Anne experienced what happened

One of the most basic functions of Free Indirect Speech is to enable “the transition from narrative to dialogue in Direct Speech, or to a train of thought in Direct Thought”. Free Indirect Discourse is free because there are no “he said” markers, indirect because it fits with the surrounding narrative: its tenses are made to align.

In the eighteenth century, authors often withdrew all narrator presence to create a fictional reality. A novel of letters immerses you directly into the fictional world. The advantage of Free Indirect Discourse is that you can keep the narrator but still immerse the reader in the fictional perspective. Austen achieves this by removing the “he said” markers. “Austen often audaciously dispenses with such signals, and instead guides the reader to read dramatized scenes of dialogue … via the transitional use of FIS.”

This sentence from Burney’s Camilla is an example.

Lionel, the little boy, casting a comic glance at Camilla, begged to know what his uncle meant by a sharper look out?

The boy has asked a question. There is a question mark. But there are no speech marks. So the transition from narrative (“Lionel, casting a comic glance”) to speech is smoothed. The question mark makes this not-quite a part of the narrator’s voice.

Now look at this extract from Pride and Prejudice.

In the intervals of her [Lady Catherine’s] discourse with Mrs. Collins, she addressed a variety of questions to Maria and Elizabeth, but especially to the latter, of whose connections she knew the least, and who she observed to Mrs. Collins, was a very genteel, pretty kind of girl. She asked her at different times, how many sisters she had, whether they were older or younger than herself, whether any of them were likely to be married, whether they were handsome, where they had been educated, what carriage her father kept, and what had been her mother’s maiden name?—Elizabeth felt all the impertinence of her questions, but answered them very composedly.

Shimazaki notes that the previous questions are asked according to the conventions of indirect speech “whether they were handsome”, but the final question with its “what” becomes more conversational, more like Free Indirect Speech. This is the first time Lady Catherine appears in the novel, though we have heard much about her. The transition from Indirect Speech to Free Indirect Speech means “the distance between Lady Catherine and the reader is gradually reduced, as if she is emerging from behind a veil.”5

We see the technique again in this passage from Persuasion.

Once she [Anne] felt that he [Wentworth] was looking at herself—observing her altered features, perhaps, trying to trace in them the ruins of the face which had once charmed him; and once she knew that he must have spoken of her;—she was hardly aware of it, till she heard the answer; but then she was sure of his having asked his partner whether Miss Elliot never danced? The answer was, ‘Oh! no, never; she has quite given up dancing. She had rather play. She is never tired of playing.’

What you see in bold is an indirect quotation. It has no speech marks, but a question mark, so it echoes Wentworth. This might seem like a quibble, but look at what Shimazaki says,

This suggests that the narrator is (or pretends to be) uncertain of the content of Wentworth’s question. Compared to the speech in DS and IS, where the narrator is in complete control of the quotation, with an introductory clause such as ‘he said’, this proto-FIS is independent of the narrator’s authority. Instead, it reflects Wentworth’s personal view of Anne, as it is re-created in her own imagination.

Austen is not showing us what happened: she is showing us how Anne experienced what happened, and the Free Indirect Speech technique allows her to do that in a way that immerses the reader in that perspective, rather than clunkily telling them about it.

In Emma, Austen’s most accomplished novel, Shimazaki sees Free Indirect Speech as the crucial element. The standard critical account of Emma is that Free Indirect Discourse is used to tell the story from Emma’s point of view, so that readers share in her errors, allowing Austen to ironise those errors and show readers the limitations of Emma’s perspective.

David Bell has described Emma as a detective novel. It is full of clues that attentive readers can use to unravel the plot. “Hints for revealing ‘mysteries’ are fragmented throughout the novel, but words and deeds of Frank, and other key characters, are made ambiguous so that the reader does not notice facts that Emma herself cannot perceive.”

Shimazaki argues that Free Indirect Speech is the crucial technique Austen uses to achieve this effect. She asks whether this is really a detective story: none of the clues is hidden. Austen’s readers would be used to reading Gothic fiction, where there were clues hidden in the plot, but a novel like Emma raised different expectations. Rather than solving a mystery, the reader is supposed to use the “clues” as part of Austen’s challenge to make us see Emma’s flaws.

Austen’s challenge is that the more ironic she is, the more of the plot she risks revealing. Every time she opts for irony, she is revealing a little more of the mystery. Using Free Indirect Discourse to keep the narrative entirely from Emma’s perspective solves that problem. We stay inside Emma’s head, and so even when Austen ironises, we are limited by Emma’s perspective.

Shimazaki says that Austen does this with both Free Indirect Thought (as critics already note) and Free Indirect Speech. By letting us share Emma’s thoughts, and intentionally directing us away from seeing Mr. Elton and Frank’s thoughts too directly, Austen creates a plot that we are blind to on first reading, but which seems loaded with double meaning on second reading.

Here’s a passage when Mr. Elton is begging off attending at a party. What we don’t know until our second reading is that while Emma is planning to matchmake Harriet and Elton, Elton wants to marry Emma, and neither of them understands the other.

[He] was to ask whether Mr. Woodhouse’s party could be made up in the evening without him, or whether he should be in the smallest degree necessary at Hartfield. If he were, everything else must give way; but otherwise his friend Cole had been saying so much about his dining with him—had made such a point of it, that he had promised him conditionally to come. [FIS]

Emma thanked him, but could not allow of his disappointing his friend on their account; her father was sure of his rubber. [FIS] He re-urged—she re-declined. . .

Elton is fishing for the chance to be close to Emma. Emma has no idea! His motives are smuggled in with Free Indirect Speech. It is not until we read this knowing what is really going on that this becomes obvious. What looks like his over-formal, almost vulgar speech, is in fact awkwardly hilarious, more so when we see how little Emma has understood this is not just a too-polite demurring, but an attempt at insinuation.

Shimazaki shows five stages of plot concealment.

Focus our attention on Emma’s preoccupations.

Fragment facts within the speech of other characters whose motives Emma misinterprets.

Contrasting Emma’s perspective to that of the Knightley brothers.

The shift to direct speech as the truth emerges.

Emma’s reflection on her actions and Mr. Elton’s speech.

“Austen uses various FIS functions in order to manipulate the reader’s interpretation on a first reading, but conceals the real plot development within the same FIS sentences.”

The same happens with Frank Churchill (who uses more FIS than any other character). Once again, Austen “directs the reader’s attention to Emma’s romantic interest in Frank, in order to divert the reader’s attention from the speech of Frank and Jane embedded in FIS.”

This summary is already too long. But I was fascinated by Shimazaki’s argument and I hope it gets more attention in Austen studies. It really does seem to be the case that Free Indirect Speech (as distinct from Free Indirect Thought) is a distinct and important narrative technique.

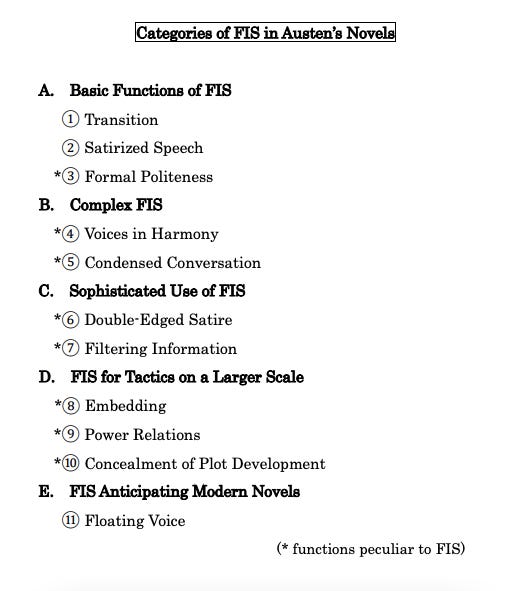

Shimazaki identified eleven types or uses of Free Indirect Speech in Austen’s novels. For instance:

‘Transition’ is the way FIS enables a smooth shift between the narration and dialogue; 2. ‘Satirized Speech’ describes the narrator caricaturing a character by mimicry of their speech. 3. ‘Formal Politeness’ is a way to express formality of speech and attitude.

“Around 1980, the first book-length studies of FID by Roy Pascal, Dorrit Cohn, and Ann Banfield were published, and proved a significant influence on Anglo-American criticism by introducing the concept and promoting the study of this style.30 Literary critics have since undertaken the examination of FID. Some significant European criticism was also translated around this time, among which Mikhail Bakhtin’s theory of polyphonic voices in the novel stimulated much discussion.

However, once the term and concept of FID became familiar, literary critics dispensed with empirical study of this mode. Instead, they borrowed formulations of FID from theorists like Bakhtin and Pascal, and applied them to various features of eighteenth-century literary culture. For example, Margaret Anne Doody argues that in the eighteenth-century ‘a woman is not supposed to be judgemental’ but modest. Women writers therefore used a character’s thoughts to present their opinions, using ‘style indirect libre’ [FIT] incorporated with third-person authoritative voice. Gary Kelly notes that the rise of ‘gentrified professional middle class Anglicans’ helped to form the national identity. Austen’s novels, where the voice of the narrator and inner voice of the protagonist share the same language in passages of FID, became a medium for the spread of standard English.34 The late eighteenth century was also the age of sensibility, and Clara Tuite examines the interiority of characters presented in FID. She argues that FID is used to focus on a sympathetic aspect of characters, such as Elinor Dashwood in Sense and Sensibility (1811), rather than emphasizing the narrator’s voice for realism. Interesting though all of these arguments may be as investigations of the potential of the dual voice as a vehicle for ideology, there is a need for the different approach I take here. I would argue that we should return to empirical research on the stylistic aspect of Austen’s texts in order to gain a more comprehensive sense of how FID operates as a technique. While previous critics may have taken an interest in what they have loosely defined as ‘FID,’ they have failed to cast a light on the parts of Austen’s novels in which FIS is subtly used.”

“Until the modern-style punctuation marks became prevalent by the 1740s, I find other methods to present DS co-existed. Parentheses were used to enclose verbs of saying, while comma marks were used to separate verbs of saying from what was said. Italics were used either to indicate the speech part or verbs of saying in order to make their distinctions. Dashes were sometimes used to introduce DS. These different kinds of punctuation marks were sometimes used together with quotation marks.”

“The technique is used for the first speech of Robert Ferrars in Sense and Sensibility (Vol. II, Chap. 14), Mrs. Hurst in Pride and Prejudice (Vol. I, Chap. 8), Fanny Price in Mansfield Park (Vol. I, Chap. 2), and Mrs. Smith in Persuasion (Vol. II, Chap. 5).21 Transitional FIS is often followed by DS with a subject clause which includes ‘added’ or ‘continued’. Thus, the author guides readers to identify the prior sentences with the distinctive style as part of the speech of a newly introduced character and allows them to read on smoothly.”

Thanks for this Henry - lapped up this information. I really wish I was studying Emma at Uni - it’s my favourite Austen novel. I’m glad though that I will have the opportunity to study 2 of her others, so I shouldn’t complain. I will look forward to focusing on FIS in the hands of the maestro!!

Always here for a shout-out to Burney! So underappreciated.