Can culture make progress?

John McWhorter recently wrote a defence of Great Books in the New York Times. He offers the standard argument that Great Books (some version of the Western philosophical and literary canon) make us struggle with hard moral questions and therefore improve us as people. This can, no doubt, be true. Reading seriously can be instructive. But I think McWhorter makes the same mistake many humanities apologists makes: his argument is about inherent quality. Of course reading Kant or Plato or Jane Austen is a good thing. The question is whether it is still worth doing relative to other things.

Reading old books is an opportunity cost — we could spend that time reading new books. Why read Kant when modern philosophy is available? We don’t read old engineering textbooks. Similarly, many people defend Latin as a good subject without realising that it can be both good and pointless.

An argument against the Great Books is given by Ryan Murphy in Works in Progress. He says that people’s revealed preferences show they want new culture, not old. That means that, given the choice, people pick modern books, movies, etc rather than going back to the classics:

in a given field of art or practice, if we can replicate a near approximation of a historical masterwork at a cost no higher than it was in the past, and we’re doing something else, that something else is probably better than the supposed historical masterwork.

This is too simple. People may not have prints of great historic art on their walls, but the museums and galleries are full. Murphy says a print gives “80% or more of the impact of experiencing the original”; revealed preference suggests to me that seeing the original is an entirely different experience to having a print. It is non-substitutable.

Murphy argues that cultural experts are pessimists about the decline of culture. He demonstrates that they are wrong and argues for the idea of cultural progress, comparing, in one example, Adam Smith’s prose and Malcolm Gladwell’s. Gladwell is infinitely easier to read, and therefore better. This is playing on easy mode, of course; Gladwell is no Smith. But let’s take the argument on its own terms.

It is certainly true that English prose has been through a prolonged process of simplification. And that this is all to the good. But for every excellent book by someone like Malcolm Gladwell or Michael Lewis there are dozens of mediocre, boring, or straight up execrable books in the same genre. Murphy says, “If someone had been able to write as effectively as Gladwell now does a hundred years ago, they would have done it. They didn’t.”

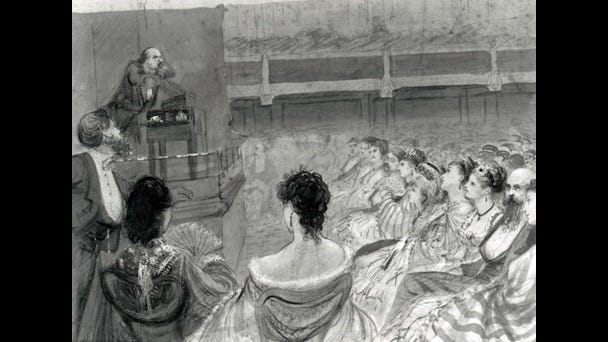

This is untrue in a very simple way: writers like Frost, Hemingway, and Fitzgerald were writing in the plain style a hundred years ago. Not to mention non-fiction writers like Lytton Strachey. But it is untrue in a bigger sense: Murphy assumes a consistent level of context. Part of what makes old books less accessible is that we lack all the assumed context. Reading Dickens can be a chore because of the syntax and the long words and unfamiliar Victorian culture. This clearly wasn’t a problem for the thousands and thousands of people who went to his live readings or who bought his fortnightly editions. He was the Netflix of his day. Who knows whether Gladwell will be readable in a century or not? It is thought that Shakespeare wasn’t entirely accessible even to his contemporaries — that didn’t stop him being popular.

If you can break through that culture wall, however, a lot is on offer. Here’s Bryan Caplan talking about his love of Tolstoy.

You love Tolstoy because here’s a guy who not only has this encyclopedic knowledge of human beings — you say he knows human nature. Tolstoy knows human natures. He realizes that there are hundreds of kinds of people, and like an entomologist, he has the patience to study each kind on its own terms.

Tolstoy, you read it: “There are 17 kinds of little old ladies. This was the 13th kind. This was the kind that’s very interested in what you’re eating but doesn’t wish to hear about your romance, which will be contrasted with the seventh kind which has exactly the opposite preferences.” That’s what’s to me so great about Tolstoy.

Whereas we know that Tolstoy offers this, we do not yet know who the best modern authors are. To work out which are the best restaurants in a given city today, you need to know a lot. It is almost impossible to keep up. Over time the hive mind runs a selection process. Bad restaurants close; good ones remain. Something similar is true with culture. There are many modern writers who I think will make it through the selection process. Time will tell.

This doesn’t mean, in and of itself, that modern culture is better or worse than old culture. It demonstrates how the selection process is as much directed at adaptation as at progress.

What Murphy missed, I think, is the relevance of the Alchian and Allen theorem. This says that when you have two goods, one expensive, one cheap, and the price of both goes up by the same amount, people consume more of the expensive one because it becomes relatively more affordable.

Going to the movies is expensive and difficult relative to watching Netflix. Cinemas got relatively less affordable after online streaming took off, so now they are struggling. Why drive and pay £12 when you can stay home and watch all month long for the same price or less?

Literature and old forms of culture more generally, have not declined in price. As Murphy says, we can all get so much more of it. But the “accessibility price” is higher: lack of context makes Dickens less popular. You have to know a lot more to get the benefit of reading Dickens than of watching the Sopranos. That is change, not progress.

This affects the way we consume modern culture, too. As Tyler Cowen says, the benefit of things like YouTube comes from “high upfront ‘investment in context’ costs”. Imagine watching an advanced, innovative chess match for the first time, having never played chess before. This is what it would be like to read Jorie Graham, having never read a poem before. We don’t get that with much popular culture because we are so immersed in it. Popularity is like high tide. We don’t know what will still be understandable when the tide runs out.

The progress is not in the quality of the culture, then, but in the variety and accessibility of it. Television is not better than Dickens, but the internet is better than the Victorian cultural landscape. Murphy is right that there has been progress, just not in the way he thinks.

To disprove the cultural pessimists, Murphy shows that television plots have become increasingly elaborate. Indeed, television plots are unimaginably better than they were. But has he read Bleak House? This is not new. He is right that detective novels are much better now in the sense of being more complex, having more techniques, and generally getting more sophisticated. But it is false to generalise from that about culture more broadly. The nineteenth century novel was a powerhouse of improvements in complex plotting.

Television is going through a golden age because of a new economic structure as well as the improvements in plotting and dialogue. Dickens flourished because the crash of 1825 changed the publishing market and enabled serialised novels; in the same way, programmes like the Sopranos were possible because of the proliferation of channels and audiences.1 Now, this has gone further with streaming, which allows programmes to be the right length and format for their content, to appeal to niche audiences — and experiment. The novel was the dominant form of the nineteenth century. Later on, as technology opened up new markets, movies took over, then television. Now we are probably moving into a period where video games will be dominant.

It is, in fact, quite easy to find further parallels with Dickens and the Sopranos. Both excel at minor characters, especially crooks, vexatious old women, and unreliable experts. Psychiatrists are to the Sopranos what lawyers are to Dickens. The Sopranos narrative is focussed on Tony but moves around to other members of the gang or to his relatives: an innovation we see in Dickens. All of the characters in the Sopranos feel at once real and exaggerated — a very Dickensian technique. Like Dickens, Sopranos creator and writer David Chase wrote about themes from his own life. He also once selected Great Expectations as one of his favourite books. Whatever else they do, the Great Books influence modern culture, unavoidably.

And this is exactly the point. We don’t read Dickens as much as we used to for many reasons. We lack the context; we have many other things to do in the evening; his language has gone out of date. But that doesn’t mean culture made progress: it adapted. It is difficult to see that modern television is better than the nineteenth century novel, just because it is now preferred. If there was such a thing as a context deflator for culture, I suspect Bleak House would be worth about as much as the Sopranos in comparable values.

It is easy to think experts have a closed shop over culture analysis, as Murphy suggests. For a long time, Dickens wasn’t much rated by the highbrows, being thought of as “popular” and therefore lowbrow — much as Murphy suggests about cultural professionals and modern culture today. Over time, as we lost context, Dickens became more difficult to “get” and so he has gone up in status.

But Dickens has also gone up in status because he lasted. He is popular. The critics gave in to the judgement of the readers. It is impossible to see what will last from your own culture. You have to wait. Just because the experts are wrong about modern culture, doesn’t make this a matter of progress.

What Murphy almost got right is that it is the common reader, not the experts, who decides what we keep and what we ditch. To that extent Murphy is arguing with a straw man. Revealed preference tells us people prefer the Sopranos — but also that Jane Austen is still wildly popular (even if she is widely misunderstood).

Murphy says, “If one can’t imagine the removal of items from the Western cultural canon taking place, then one’s paradigm may be inconsistent with even the possibility of cultural progress.” But that is exactly what does happen. Dickens survived, but many hundreds of other writers did not. They were weeded out along the way. The canon is constantly changing. The judgement of the common reader is supreme with the old and the new.

The funny thing is, we already know this. Literary types might not be very keen on taking lessons from economists (although they ought to — and vice versa) but Samuel Johnson said a lot of this already. It was the common reader who got to decide which were the great poets, he said in the Life of Gray. In the Life of Waller he told us, sounding remarkably like Murphy, that “compositions merely pretty have the fate of other pretty things, and are quitted in time for something useful.”

So let us do away with the idea of progress in culture as a battle between old and new. (Jonathan Swift knocked that old chestnut on the head already). We don’t need to be pro or anti Great Books or modern culture. We can have both! Let’s take a more Johnsonian view. Culture is entertainment. It can, and often should, have moral value. What is good is what lasts and what is popular.

Above all, culture of any form is not to be favoured above living or above utility. In the Rambler 180 Johnson said that “instead of wandering after the meteors of philosophy” students ought to remember to live and learn about “moral and religious truth”. And this truth is not always to be found in literature — or entertainment culture generally. It can be and often is; but Johnson is clear. Art is not always the best mode for learning.2

Reading great books, says Johnson, is necessary. “It is only from the various essays of experimental industry, and the vague excursions of minds sent out upon discovery, that any advancement of knowledge can be expected.” Read; read widely; read ancient and modern. Johnson told his servant to read to make himself wise. And he told the bookish that too many of them “who compare the actions, and ascertain the characters of ancient heroes, let their own days glide away without examination.” Don’t take books too seriously, in other words. Live your life.

Artistic and imaginative culture does not make as much progress as Murphy thinks and it is less essential than McWhorter believes. Culture follows progress. It changes as technology and audiences change. It is easy to over rate (and under rate) it. Read, watch, listen, and look at what you enjoy and benefit from. Don’t take it too seriously, but treat it as more than just something to pass the time. It won’t make you a better person, but it will, as Johnson said, help you better to enjoy life or endure it.

In short, be a common reader.

Other relevant articles from The Common Reader

Do real artists write schlock?

The Anthologist, Nicholson Baker

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying The Common Reader, let your interesting friends know what you think. Or leave a comment at the bottom.

If you don’t subscribe to The Common Reader, but you enjoy reading whatever’s interesting, whenever it was written, sign up now.

The crash of 1825 was a major turning point, politically and economically. It also opened up the book trade. Alexander J. Dick explains that one result of the crash was the emergence of mass market books.

Taking advantage of the misfortunes of their former competitors, smaller publishers like Thomas Tegg began to buy up their stock at a fraction of the original costs and reissue them in cheap editions (Sutherland 157). Other publishing entrepreneurs such as Charles Knight and Henry Coburn soon followed Tegg’s lead and the market was soon awash in affordable editions. The equation, assumed by Murray and others, between literary reputation and expensive, limited editions was superseded in the market by the idea that financial reward came from mass sales. Indeed, establishment publishers responded in kind. Murray began issuing his Family Library and Longman the Cabinet Encyclopedia (Hilton, Mad, Bad 20). The vogue for these series reached its apex in the early 1830s with Scott’s Magnum Opus and Bentley’s Standard Novels. The demand for cheaper fiction after 1826 also inspired one of the most crucial literary trends of the nineteenth century: serialization.

From here on out, Victorian novels would straddle “the divide between academic and popular markets that the 1825 crisis had opened up.” https://www.branchcollective.org/?ps_articles=alexander-j-dick-on-the-financial-crisis-1825-26

Johnson’s Life of Waller contains the famous line: “The essence of poetry is invention.” Because of this, Johnson was sceptical about religious poetry. Religion is a known quantity according to Johnson; versifying it is pointless.

Of sentiments purely religious, it will be found that the most simple expression is the most sublime. Poetry loses its lustre and its power, because it is applied to the decoration of something more excellent than itself. All that pious verse can do is to help the memory and delight the ear, and for these purposes it may be very useful; but it supplies nothing to the mind.

We might be surprised to hear one of the all time great apologists for literature dismissing poetry’s ability to do anything useful or meaningful in what was, at the time, a huge and important area of life. It is easy to see how this applies to much scientific and social scientific thought and its place in literature today.