Children need more reading time, education needs less politics

This is just common sense

We all need to care more about this!

…it turns out that a lot of school districts now use reading curriculum packages that don’t feature whole books, just passages. Some people say this is pressure to “teach to the test.” But kids taught this way don’t do better on reading comprehension tests — they do worse. The best explanation, according to Vaites, is that the passages method is cheaper. Of course, if you’re accountable for results, you’re much less likely to just go with the cheapest option. If you’re accountable for results, you go with an option that works.

Matt Yglesias explains how changes in US education policy over the last few years have resulted in the lower 12th grade reading scores that were published recently. In an age where everyone likes to make everything a political discussion—and indeed when the government is heavily involved in education—it is so easy to get away from what we know that works. I am not commenting on anyone’s political ideas, merely saying that the fact of making this a political argument is part of the fundamental problem. Why subject the fate of children’s literacy to such a volatile and polarized culture? Especially when there is no great mystery at the heart of teaching children to read…

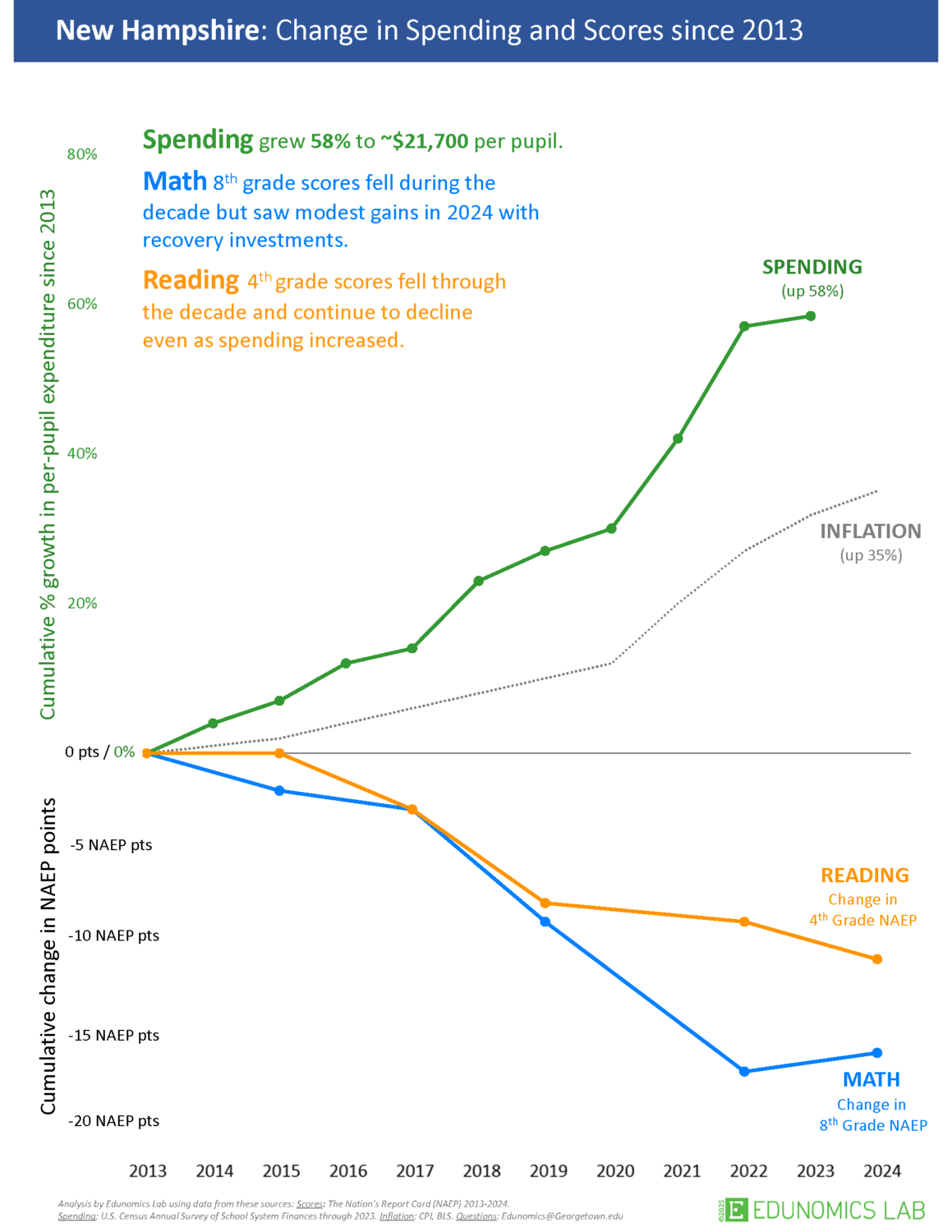

A lot of education doesn’t come down to funding, even though all political debates do. Obviously, sometimes spending levels do matter. But this graph shows that New Hampshire increased education spending significantly above inflation without seeing any educational attainment as a result. More money isn’t always the answer.

Education is really about successful policy decisions, like those made in England.1 Fundamentally, that is about attitudes. There is more than enough money to teach children to read; the question is how people are choosing to spend that money. As Matt says,

Of course there are extrinsic factors at work — digital distractions, a pandemic, often troubled home lives, etc. — but on some level we’re suffering mostly from a big national failure to take the educational goals of the school system seriously. As I wrote in the inaugural issue of States Forum over the summer, this is particularly egregious in the bluer states, where the levels of spending on K-12 education are much higher but nobody wants to ask the basic questions about whether appropriate curriculums are in use or whether schools are doing a good job.

When my own children were younger, I made them an offer. You can stay up for a later bed time, I told them, if you use that extra time to read in bed. This was a win-win. They already did quite a lot of reading, but this guarantees something like an hour or ninety minutes of reading a day. Not everything they read is The Hobbit or Peter Pan. They get through piles of Skandar. But the basic question of getting children reading comes down to the task of organizing their time and implementing incentives. A lot of children are suffering educational malaise because of possibly intractable social problems, but what is needed are simple incentive structures that prioitize reading time, not political debates.

Education is a good thing in itself. It is an end as well as a means. Children ought to be able to read well for their own sake, not just because it will improve their lives, though it will that. The freedom of their minds matters a lot more than whatever debate is taking up air time this week.

Some people cannot read sentences like that without feeling very strong political feelings about Michael Gove. Well, look at the PISA data: England continued to do well while the OECD average declined. PIRLS confirms this: English children continue to read well while other countries saw a decline. PIRLS found that the Year 1 phonics test which the Gove program introduced was associated with higher reading scores later on. Phonics screening also lead to the “Mississippi miracle”. We mostly don’t need to debate the politics of education: we need to follow the data.

Thank you for continuing to be a voice of reason around this subject. As a former English teacher who was forced to implement some rather silly reading intervention strategies, my administration never could quite grasp the simple idea that giving children time and space to read—without the pressure of a test or a quiz looming over them at every turn—really is a better use of their time.

The best success I had was with a class of 9-12 grade students who were lumped together as "poor readers" and handed to me for a semester to do whatever I could with them, with the expectation that the school would not offer me any resources (nor, conveniently for us, any real oversight). These kids were "reluctant," so-called, because they had been conditioned to dislike reading by their environment and their experiences in the classroom from an early age.

To make a long story short, the students and I worked together to incrementally build healthy reading habits, including plenty of time to think, write, and talk about what they were reading. They primarily read what they chose to read, with some works selected by myself from news clippings, criticism, and short classic texts. By the end of the semester, most of these students would be entirely focused for a full 30 minutes of in-class reading time, and some would become upset with me when I told them that they needed to pause and get ready for their next class!

It really is quite simple.

There is a saying in US public schools, “Don't value what we measure; measure what we value.” Unfortunately, with standardized testing being the most important aspect of all things in public schools, we communicate that is the only thing we value because we place so much importance on these measures. If we want kids to read more, and for leisure, we must realign our values away from testing and more toward literature. It’s easy. Reward reading great literature.