Horatio Nelson: The Darling Hero of England

Happy Trafalgar Day. It's time to revive the Great Man Theory of History

“The greatest victory ever achieved—but…”

The Admiralty was shrouded in fog. The messenger arrived at one a.m. He had ridden 31 horses and post-carriages over 271 miles since landing in Falmouth two days earlier. Lieutenant Lapenotière saw the First Secretary of the Admiralty just a few minutes after his arrival. He was carrying the dispatch of Admiral Collingwood, which contained the news from the Battle of Trafalgar. It was 6th November, 1805, sixteen days after the battle.

Now lamps were lit, and the news was hurried around London. The Prime Minister, Pitt the Younger, was woken, as was George III. They sat in silence for several minutes, shocked. In 1803/4 there had been an invasion scare and the country mobilised to defend itself against the coming of Napoleon; earlier in 1805 Admiral Nelson had chased the French fleet to the Caribbean and back as they manoeuvred in preparation to take the Channel, an attempt only let down by Napoleon’s ineffective Admiral Villeneuve.

England had been waiting for this dispatch from the seas.

The great naval battle of her history had been anticipated. Victory meant the defeat of tyranny and the defence of freedom; failure meant, quite literally, the breaking of British naval power. All hope held its breath, waiting on the daring genius of Admiral Horatio Nelson, celebrity hero of the fleet, who had, in his great courage, already lost an eye and an arm in the service of his country. News of his victory at the Battle of the Nile in 1798 had set off celebrations. Now Nelson must outdo himself, or Napoleon’s navy will do for him.

Nelson was fond of quoting Shakespeare. Like Shakespeare’s hero king Henry V, Nelson walks among his men the night before battle. He and his captains are truly a band of brothers. Like Henry, too, he is known so much by the legend of his heroics that it might be forgotten what a stern and fierce thing it is for a man—a boy from a Norfolk parsonage—to become a terrible god of war. His career has been one of the utmost daring—leaping in battle from ship to ship, always engaging the enemy more closely, never shying from the rush and cry of combat. He lives for honour.

At Trafalgar, this spirit of amazement must prevail, or England herself will stand in great peril. As he has done before, Nelson takes a sharp, intelligent, startling approach. At first it looks as if England’s fleet will sail up and align alongside the French to fight ship-to-ship, man-to-man. But then, with the warlike flourish for which Nelson has become known, the English tack. No longer heading up to sail beside the French, they are heading suddenly, like a change in the wind, right into the middle of the French line of ships.

Nelson is simply going to cruise through the middle of the French fleet.

Now chaos and disorder reign. The French are scrambling to maintain some coherent position. Nelson has arrived in fierce tempest. The French are scattered. The English crowd around and among them. Support between French ships becomes impossible. Like a hunting pack, the English have stunned the French, disoriented them, and as they are dispersed, England’s navy releases the intemperate thunder for which they are famous, firing three shot of cannon for every one of the French. And so they pick them off, one by one, with great rows of blast and flame.

This is England’s finest hour. Nelson’s too. Trafalgar Day is still commemorated by the Navy every year, with a toast to the immortal memory. It served as inspiration in the Second World War.

The news arrives at the Admiralty. “The most glorious victory ever achieved!” But amidst the lightness of great relief, something darker forebodes in the messenger’s face. There is something more.

“The greatest victory ever achieved—but Nelson is dead!”

England’s darling hero?

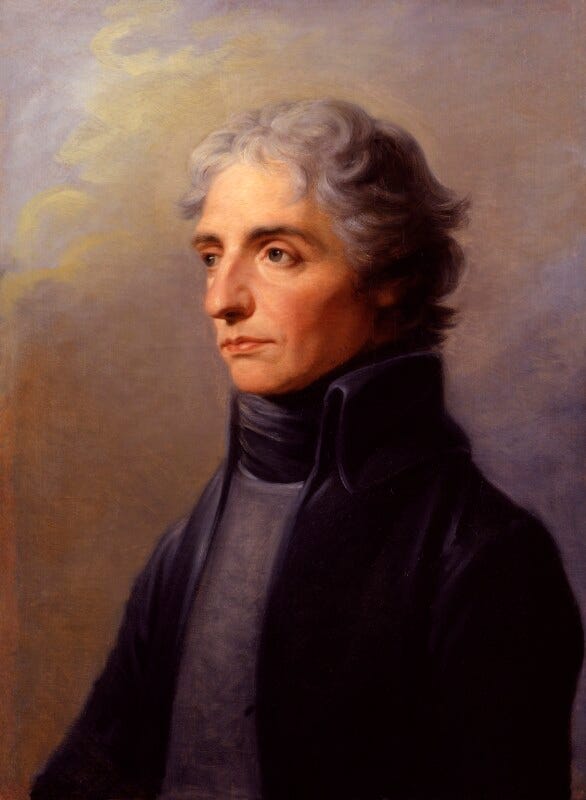

To his contemporaries, and to the Victorians, Horatio Nelson was a hero. Not just any hero. He was the hero of heroes. The Poet Laureate Robert Southey, in his biography of Nelson, called him “England’s darling hero”.1 Byron called him Britannia’s God of War. England would not know another figure of that magnitude (other than the Duke of Wellington) until Churchill. Nelson was truly Homeric in the English mind.

Several times a week, I walk through Trafalgar Square, past Nelson’s Column, still the highest monument Britain has built to anyone. Every day, tourists crowd the base, photographing each other in front of Landseer’s lions and the reliefs that honour the men who fought and died at Trafalgar. But apart from St. George’s Day, when Nelson is occupied by men wrapped in the English flag, I see no British people paying any attention to Nelson.

For a country that was once so proud of its history, we are strangely detached from it. Nor are we so proud anymore.

In 2013, 86% said they were proud of Britain’s history. Now the figure has fallen to 64%. Polling suggests that 37% of British adults don’t know the dates of the Second World War. 40% of them don’t know what the Blitz was. Less than half of us know that William Wilberforce campaigned to abolish the slave trade. Although 90% know that Nelson was the Admiral at Trafalgar, only 35% know where the battle took place.

21st October is Trafalgar Day. Who commemorates it now?

There was a time when Trafalgar Day was a national event. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Trafalgar Day involved parades, dinners, and celebration. In the aftermath of the horrors of the First World War, the celebrations declined. But even until the Second World War era, it was noted on the radio. Twice it has been mooted as a new national holiday (in 1993 and 2011). It should be made into a Bank Holiday.

Still, the immortal memory lives on. Wreaths are laid in Birmingham and the signal “England expects every man to do his duty” is made in Edinburgh. The Navy holds a celebratory dinner every year. And Nelson still stands. Other statues have come and gone. Nelson remains.

But Nelson has become something of a National Trust phenomenon. Again and again I talk to people who want to know about this great hero, who wish they had been told about him at school, but who admit they are ignorant. Instead of being like Churchill, someone we all know the basic facts about, who we can quote, whose accomplishments are widely known, Nelson is more akin to a stately home—many visit, but many more do not.

Historians have been involved in a flurry of Nelsoniana discoveries in recent years. The known quantity of Nelson papers was extended by a remarkable twenty percent—a whole fifth—in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. For the two hundredth anniversary of Trafalgar in 2005 multiple books were published about Nelson. Some were adulatory, some revisionist. In general, there was a trend towards two things.

First, nuance. Battle narratives became a question of what really happened, a comparison of logs and records. The reader’s basic instinct to know who was shot and when is often frustrated by this tendency to bring the footnotes into the narrative. (And without a glossary of nautical terms the ordinary reader will feel numbed by all the rope and sail talk.)

Second, there was the historian’s love of the “vast impersonal forces” of history. From Southey’s darling star, Nelson fell into a man at the head of a remarkable system. The great man theory of history is disliked by historians and Nelson was—amidst much praise—quietly removed from his Victorian pedestal. John Sugden’s exceptional two volume biography resisted some of these tendencies. But at two thousand pages across two volumes, it is not widely read.

And so our ignorance about one of the most important figures in our history carries on untroubled. But without Nelson, Napoleon may well have achieved what Hitler never managed.

It was Horatio Nelson who saved England. He was truly a Great Man of History. He ought to be our darling hero once again.

Trafalgar: battle of temperament

Although he had a logistical challenge in getting his troops across the Channel, between 1803-1805 Napoleon massed up an army of up to 167,000 men on the north French coast. By 1804, some 11-14% of adult British men were enlisted, three times higher than the French proportion. England was under the scare of invasion, of losing her naval power, and of civil disobedience.2 The government had issued instructions for priests to evacuate their parishes and then to go round and destroy the remaining property that could not be transported out.3 Eventually, this scorched earth policy was abandoned, after opposition in Sussex, where invasion seemed likely. Anticipating large numbers of people fleeing the coasts, food was stockpiled in London. Lists were made of all possible landing spots and how they would be used in different weather conditions.4 Floating batteries were established on the mouth of the Thames, using old ships mounted with twenty-four pound guns. The very mention of “Boney” made coastal people so anxious, it was remembered and talked about by their grandchildren and great-grandchildren a century later, having passed into family and village lore.5 Beacons were established all over the country, to spread the news of invasion quickly; church towers were adjusted to hold fires; it became a criminal offence to strike a light too close to the sea at night.

That is why Trafalgar became such a mythic event in British history. Although Napoleon had broken camp and marched to Austria in August 1805, two months before the battle, Martello towers continued to be built along the coast until 1814; military planners were worried about invasions again from 1807-1812.6

Nelson was flocked by a crowd when he left Portsmouth in September because he symbolised the hope of Britain’s resistance, not just of anti-French patriotism, but of all the men and women drilling arms after Sunday service, working to increase agricultural output, and reinforcing national defences. It was an age of blackouts, signals, preparations; a time of muskets, military roads, “Armed Associations”, and pikes. The invasion scare became ordinary life; Napoleon had subjugated Austria, Italy, Switzerland, Elba, and Piedmont, to his rule already. Britain was jealous of its colonies and power, protective of its trade, but also scared for itself.

As Edward Fraser wrote in 1906, the importance of Trafalgar is that “the mad dog was still about the village—Nelson shot it dead.”7

Many explanations are given for Britain’s victory at Trafalgar: the better diet and discipline of her seaman; the ability to fire three shots to every one of the French; the advanced and modernised bureaucracy of the British Navy. This leaves out the important question of temperament. It is a view of history that puts the emphasis, in Professor Sir David Canadine’s words, on the importance of “processes”.8

But Trafalgar cannot be explained by process alone. It was a clash of personality.

According to one French officer, the French admiral Villeneuve, who was leading the Franco-Spanish fleet “was haunted by the spectre of Nelson.” He had been so ever since the Battle of the Nile, seven years earlier.

Villeneuve was right to be afraid. Where Nelson was decisive, Villeneuve vacillated. Where Nelson was strategic, Villeneuve was disorganised. Where Nelson was fierce, Villeneuve was weak. Nelson’s leadership unified the British fleet, even though many of the captains hadn’t sailed with Nelson before. The French fleet lacked all cohesion. Nelson’s plan was known in the bones of each of his captains. Villeneuve anticipated Nelson’s plan of attack, but made no counter-plan of his own.

Imagine if the temperaments of the admirals in the two fleets were swapped, if Villeneuve and his men’s attitude could be replaced with that of Nelson and Collingwood. It is hard to believe that the battle would have turned out the same way. Too much credit can be given to Nelson, but the immense contribution of the example he had set, year after year, battle after battle, cannot be underestimated. He was a product, no doubt, of the processes he had been through, but few people of Nelson’s qualities ever emerge from such processes.

Trafalgar was not won by mere systems, but by Nelson’s flair, his bravery, his beliefs, his emotions. Trafalgar was a victory of temperament.

Mad courage

Most significant of all, perhaps, is that when the battle started, ten of the Spanish ships were cut off from the action. Instead of taking the initiative, they waited. Their admiral asked Villeneuve for orders. He could see his comrades under attack. He could see that the British had brought devastating chaos to the Franco-Spanish fleet and they desperately needed support.

And he waited for orders.

What a contrast that makes to Nelson, who had made his name with act an of initiative so daring it made him an overnight celebrity.

Early morning, 14th February, 1797, twenty-four miles off the Spanish coast. Slowly, Spanish ships are seen emerging from the fog. First eight, then twelve, then twenty, then twenty-five, then twenty-seven. Enough, says the commander, Admiral Jervis. We’re here now. Let fifty of them come. We’ll still go into battle.

The English are outnumbered. But they give chase. The Spanish ships are in a long line. Jervis drives his fleet right towards them. A gap has opened in the Spanish line and the English sail into it, successfully cutting off the front and back halves of the Spanish fleet from each other. But the English ships were getting separated too.

Standing on the deck of the Victory, Admiral Jervis could see that nineteen Spanish ships (including the largest warship in the world, the four-decker Santissima Trinidad), were about to overwhelm the six British ships at the front. Jervis planned to signal to the back of his line for a group of ships to sail over and assist. But the ships were shrouded in gun smoke. To send a signal down the line, ship-by-ship, would take too long. Every minute he delays the nineteen Spanish ships get closer to the six British. And the English ships he wants to turn around are heading the wrong way. They need to turn soon.

Jervis has to win this battle. In recent months the French have retaken Corsica and Spain has joined the war on Napoleon’s side. And without her sea-power, Britain is nothing. Without her sea power, Britain is conquerable.

So Jervis signals for his ships to tack towards the Spanish. Several of them do not see the signal; several ignore it. The Navy at this time is hidebound by rules, over-centralised, too dependent on these signals and, not enough on initiatives; it’s all flag patterns, not enough blood lust. Nothing happens. Until the young Captain Horatio Nelson breaks his ship out of line and makes his way towards the Spanish fleet all alone.

This is a truly remarkable action. Modern historians go to some lengths to show that Jervis signalled Nelson to make this move. The logs of Jervis’ own ship suggest that Nelson broke out six minutes before Jervis signalled. Even if we accept, though, that Nelson wasn’t being disobedient, he still didn’t quite follow the signal. To tack is to turn into the wind. Nelson, though, turned the other way. He did not tack; he wore. He turned away from the wind. He knew that otherwise he would be too late to catch the Spanish fleet.

Amazement rippled through the British ranks. Here was a junior officer breaking out of the line, in the midst of battle, taking his ship into a fight of seven against nineteen. Soon Nelson’s ship, the Captain, was in close battle with three Spanish ships. He later explained that he knew what Jervis was trying to do, to send the rear of the fleet in to cut off the Spanish advance, but he could also see what Jervis could not—that if he tacked into the wind he wouldn’t get there in time. So he cut his ship through the middle of two British ships and went headlong into battle, as he always had and always would.

Soon, Jervis signalled Nelson’s friend and colleague, Cornwallis, who later fought at Trafalgar, to follow Nelson and support him. Cornwallis came up alongside two Spanish ships, San Josef and San Nicolas, so close that when the cannon fired, the shot went straight through both ships at once. The roar and swell of battle was immense. Captain was shot ragged, masts down, sails shredded, the whole ship battered and riddled. In Navy slang, it was a crazy ship. The fighting was intense. One in three died. Nelson had been hit in the abdomen by a block of wood that knocked him sideways.

But Nelson never retreated. Seeing Cornwallis’ ship was cramming the Josef and Nicolas together, Nelson took his opportunity. The Captain smashed into the side of the Nicolas and Nelson called for a party of officers to board the Spanish ships.

Then he did what no flag officer had done in more than two hundred years, an action that deserves every bit of the glory and celebrity it brought him. Nelson drew his sword and boarded the Nicolas. No officer of his level had done this since at least the sixteenth century, possibly ever.

While the cannon roared, one of the British men smashed a galley window of the Nicolas with his musket. Nelson and a band of men armed with cutlasses, pikes, and axes, leaped through the window. The cabin door was locked, so they axed it open. As they hurled themselves out of the cabin, Spanish sailors fired pistols, felling several British men. Nelson and his men fought their way through. A second party of British sailors dropped down from above. The Spanish were overwhelmed. The British fought their way, hand-to-hand, sword-to-sword, along the Spanish deck until the flag was down.

Immediately that the flag was down, the Nicolas became a British ship. And so the second Spanish ship, the Josef, opened fire. Nelson turned. But he did not retreat. He called for the Nicolas to return fire, and he called for more men. And then he took the party who had boarded the Nicolas and led them to board the Josef too.

The commander of the Josef had lost both legs. A fifth of the men were dead. Collingwood’s attack was fierce. Nelson’s party easily overwhelmed this second ship. Nelson personally took the sword of the Spanish captain.

And he did all of this without any vision in one eye. As Edgar Vincent says, boarding these two ships was an act of “mad courage.”

This is the contrast of temperaments that determined Trafalgar. Where Nelson was focussed on executing the plan in order to win, happy to take on personal risk and to act beyond his instructions, the French were focussed on internal process and unwilling to respond to the battle that was flaming, quite literally, in front of them.

Like a terrible Jove

As he rode into battle at Trafalgar, on 21st October 1805, aged forty-seven, Nelson’s hair had been white for five years, he was missing his top teeth, and he was thin. Britannia’s God of War was rattled and frayed.9 With the exception of a few weeks at home, he had been continuously at sea for more than two years. In recent months he had chased the Franco-Spanish fleet across the Atlantic and back. His right arm had been amputated eight years earlier. He had been blind in one eye for eleven years. Walking to the Victory a month before the battle, he had pushed through cheering and adoring crowds at Portsmouth.

The next time he was flocked by crowds, Nelson was lying in state at Greenwich.

No-one knew that as he stepped onto Victory waving to the crowds that Nelson sailed to his greatest triumph and his final hour, but he had long anticipated that he would die in battle. Before every engagement, men wrote home. They remarked that they may not see each other again. Nelson was feeling old and tired. He looked old and tired. But he was none the less terrifying. Admiral Villeneuve tried to avoid battle. He was unlucky that he failed to do so. Nelson, unlike Viellenuve, would never flinch. Flagships were usually in the middle of the line: Nelson’s was at the front. He died alongside nine of his captains. This fearlessness had marked Nelson for years and years. The French well knew that he was coming in thunder like a terrible Jove.

They rightly knew what it was they had to fear. Not the English system, but the English Admiral.

Horatio Nelson: Great Man of History

The Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1793–1815) lasted a generation. They were four times longer than the two world wars of the twentieth century. France invaded Austria, Switzerland, Italy, the Netherlands, Egypt; colonial territory was contested in India; it enabled the United States to purchase the Louisiana Territory. During this conflict, it became essential to Napoleon Bonaparte, French military leader and then Emperor, to subjugate Britain. France was mighty on land; Britain controlled the sea. That control was the essential method of resisting Napoleon. Under Napoleon’s leadership, what had begun as a Revolutionary movement transmogrified into tyranny.

Everything Napoleon did to modernise and liberalise was balanced out with the spill of blood and the cry of war. Had he managed to invade Britain, to take naval control, to break British sea power, history would have taken a different course, not just in Britain but across Europe.

Napoleon’s invasion plans were finally frustrated at the Battle of Trafalgar, in 1805. Trafalgar didn’t win the war, but it did “produce the conditions which made certain the downfall of France.”10 From then on, Napoleon was contained on the continent, economically restricted, and unable to break out of Britain’s blockade. Eventually, it was Britain’s naval lock that caused the economic strain that induced Russia to abandon Napoleon.

However much he increased his naval forces, Napoleon was behind after 1805. Before the allied coalition could beat Napoleon on land, Britain had to defeat him at sea. Had they not done so, Britain may well have been invaded. Before Trafalgar, Napoleon thought that by invading England he could become dominant over all Europre, and through England’s colonies, all the world. It was, as Rene Maine said in 1957, a dream re-lived by Hitler in 1940.11

Britain’s resistance was a whole-country effort, as it later was in the two wars against Germany. Historians are careful not to repeat the enthusiastic celebrations of heroes from the time, and instead emphasise the way that all England’s systems, bureaucracies, institutions, and processes were made efficient and effective.

But the pendulum has swung too far. Victory came from the long, hard work of the entire country; it was the result of superior systems, bureaucracies, and efficiency; it was the victory of both Nelson and his admirers; it took, quite literally, in all senses, generations to win.

But all of this relied on the talents of men like Pitt, Wellington, and Nelson, men who led their organisations tirelessly, with great vision, energy, and determination. Men, in two cases, who died young as a result.

It was thanks to Nelson that Britain became unassailable at sea, thus restricting Napoleon to the continent, and creating the conditions for his defeat, as the military historian J.F.C. Fuller said. His three great victories (St. Vincent, the Nile, Trafalgar) represent a significant moment in the history of Britain as a free, industrial nation, as the country that later used its massive sea power to bring an end to the slave trade (which had been so grossly extended by the British earlier on, of course), and to maintain the system of trade networks that was so essential to the rising prosperity and advancement of the decades of innovation that followed.

Professional horror of the Great Man Theory of History has led historians to under-rate the role of exceptional talent in the course of events. But without men like Pitt the Younger in politics and Horatio Nelson in the Navy, resistance to France would have been much less possible.

Thomas Carlyle’s Great Man Theory of history, which was proposed in the 1840s, has been discredited by generations of historians. In their flight away from this, towards what the poet W.H. Auden called the “vast impersonal forces of history,” historians have lost sight of something important. Carlyle’s original definition is more subtle than saying that history is merely biography.

They were the leaders of men, these great ones; the modellers, patterns, and in a wide sense creators, of whatsoever the general mass of men contrived to do or to attain; all things that we see standing accomplished in the world are properly the outer material result, the practical realisation and embodiment, of Thoughts that dwelt in the Great Men sent into the world: the soul of the whole world’s history, it may justly be considered, were the history of these.

The important element here is that the great man is “in a wide sense creators, of whatsoever the general mass of men contrived to do or to attain.” This is Horatio Nelson exactly.

As his fleet sailed to Egypt, where in 1798 he achieved perhaps the most stunning naval victory up to that point in British history, Nelson would have the captains of each ship rowed over to his own. They dined together, and he talked them through his plans and ideas in great detail. By the time they reached Aboukir Bay, Nelson’s captains were deeply immersed in his battle tactics, but also deeply inspired by his ways of working: his intensity, his thoroughness, his determination, his passion.

Truly, the Battle of the Nile was the “realisation and embodiment, of Thoughts that dwelt” within him, and which he discussed with his captains, day after day. He embodied what he wanted them to be.

We can accept the great importance that Nelson played without believing that history is only made by Great Men. The claim is that people of high accomplishment lead, model, pattern, and create the history of high accomplishment. Some people make far more difference than others.

New research has recently shown that during the Reformation—the period when many parts of Europe were converting from Catholicism to Protestantism, an immense spiritual, political, and cultural upheaval—places that had direct ties to Martin Luther were more than twice as likely to convert.12 That is, those places which received a visit or letters from Luther, or which had one of his disciples, were much more likely to become Protestant. Vast impersonal forces were at work across Europe: the printing press, the newly vernacular Bible available to ordinary people for the first time. But the more direct contact a community had with Luther, the more likely the conversion.

Something similar is true of the abolition movement, which occurred at a similar time to when Nelson was fighting his wars. Many factors are important in the abolition of slavery: evangelical Christianity, the changing economics of trade, imperial Britain distinguishing itself morally from the newly liberated United States—but early abolition movements failed, not because these factors weren’t in place, but because their leader was utterly uncompelling. Granville Sharp was an ineffective leader of his movement; William Wilberforce was quite the opposite.13

Nelson was one of these people: without him, all the other conditions would have been in place for victory, but lacking the crucial difference he made to the hearts and minds, not just of his sailors, but to the many in Britain whose hopes and morale rested on him.

It is all too easy to see just how good Nelson was at self-publicity, how much he drew attention to himself at the cost of praising all the men involved in his campaigns. But that crowd that cheered him off at Portsmouth when he sailed for the last time means something more than ephemeral celebrity. It was a response to his leadership, to his irreplaceable temperament.

Historians often separate the strategic importance of Nelson’s victories (did the victory at Trafalgar actually affect the course of the war very much?) from the morale boost he gave to people (Britain was twelve years in to what would be a twenty-four year conflict). But those two things are much less separable than that. History does not happen in neat segregations: life cannot be philosophically divided and taxonomised while it is being lived.

To win the war, Britain needed Nelson. Even the most cynical historians have noted that after Trafalgar, Napoleon built up his fleet but was hampered by his lack of capable sailors and officers.

Temperament, the mixture of qualities that distinguishes a person, is what biography is all about. The word “temper” used to mean “attitude; frame of mind; humour”. A biography should show us someone’s temperament and how it affected their work and the people around them. Novels are often much better at this, as in Zola’s famous study of temperament Therese Raquin.

Great Man Theory is properly the idea that the temperament of a small number of people is just as essential to the course of history as the vast impersonal forces of material conditions and ideas. This is well-noted in the modern world, where we are obsessed with the temperament of entrepreneurs like Steve Jobs and politicians like Donald Trump. Temperament is everywhere acknowledged to be essential to the way events unfold.

Sometimes, there are people like Horatio Nelson, who enable a very great sense of progress in their people. We should not be scared of revering such people. They really are great.

The soul of history

Of course, the busy assiduity of the hundreds and thousands of men involved at all stages of building, financing, and taking to sea a great fleet is paramount. But so are a few crucial decisions: that of Pitt the Younger to restore the Navy to greatness when he became prime minister in 1783, which was inspired by his father’s victories in the Seven Years War, and that of Nelson who not only determined to beat the French, but to beat them on a scale unseen before.

Nelson won three remarkable victories—Cape St. Vincent (1797), the Nile (1798), and Trafalgar (1805)—by acting unlike any other admiral before him.

He gave far fewer signals than other admirals (only three to all ships at Trafalgar). He had far more faith in his men. Where others professed their faith in the superiority of the British sailor, Nelson acted on it. He knew that the French and Spanish fleets suffered from inferior training and a lack of fighting spirit. He knew that once his men could get up close for battle they could be trusted to win. Unlike the others, though, Nelson let them get up close and act without a constant stream of orders. Knowing they could be trusted, Nelson let his men act with initiative. Other admirals had over burdened the Navy with a complex system of signals and orders. It was rational and orderly, and it stifled initiative. Which is why the Great British Navy took so long to secure any major victories at sea over the French. Without Nelson, everything was pyrrhic and indecisive. With him, England became the ruler of the waves.

“Something must be left to chance,” Nelson wrote in his Trafalgar memorandum. He knew his men would follow his temperamental lead: to always engage the enemy more closely, to create conditions of chaos (a “pell-mell” battle), and to fight with the brave determination he himself had shown time and again, under fire, while injured, right in the heat of battle. “No captain can do very wrong if he places his ship alongside that of an enemy,” was a large inspiration to give to his men, and he knew it.

Nelson created a culture, a mood, a belief among his captains. He inspired them. By the time the battles began, Nelson’s work was already done: he had created an ethos and an invigorating spirit among the men. They had Nelson in their hearts and minds. What he called “the Nelson touch” was his ineffable capacity to imbue his men with the fierce sense of duty and the courage to fight not according to signals and instructions but pell-mell, rampant amidst the fog of war. Like Churchill in 1940, Nelson had the ability to bring the men sitting with him to tears as he inspired them into dogged action.

This meant Nelson didn’t win the narrow victories of his predecessors. Instead, he claimed total control of his enemy. Nothing held him back: not the nervous obedience of naval rules nor the greedy forethought of captured gold. Nelson fought for duty, for glory, for king, country, and annihilation. He could have been much richer. He could have won the wider esteem of his superiors and colleagues. He wanted something else. When England stood alone, with Napoleon massing up a great army to invade, having conquered many other countries, Nelson knew that only one thing stood between England and defeat. The sea. Without that, none of the rest could follow. And so, like Churchill, he fought for victory and nothing else.

That is why, like Churchill, Nelson continues to sail in the British imagination. That’s why he was invoked by the Navy before the First World War, and why a film of his life was thought by Churchill to be one of the most effective morale boosts in the Second World War. Nelson is a symbol of Britain at her best. Nelson commands the highest Column in England because his greatest victory at Trafalgar put an end to major sea battles.

But, also like Churchill, Nelson had many weaknesses and failures of character. The hugeness of his intrepid ego that saw him sail at the front of the line at Trafalgar (which other admirals never did) was what led him to bloody defeat at Tenerife, where he quite needlessly lost an arm only a few months after the triumph of Cape St. Vincent. He was pushy, arrogant, self-assured, careerist, and had one major episode in his career where he was seriously out of favour with the men who ran the Admiralty. Not everyone loved his celebrity. Not everyone agreed with his self-promotion. Circumstances provided Nelson with his opportunities for glory. Had war not come again in 1793, Nelson would be forgotten to us now; had he not found the French fleet in 1798, after weeks of searching in vain, he would not have gotten such a fearful reputation—so fearful that it was said before Trafalgar that the French Admiral Villeneuve was “haunted by the spectre of Nelson” before Trafalgar.

Yet, as Stephen Roskill said, “hardly had the body of the nation’s hero been lowered into its grave than the lessons he had taught were forgotten.” The navy became more “rigid” and “formalist”. Roskill says the effects were still felt in 1916, when Britain could only manage a stalemate in the Battle of Jutland, along with the loss of two ships. History is more than systems: systems rely on people. It was Nelson who inspired his men—with his presence, his writing, his example, his talk—to fight like they fought at Trafalgar. Once he was gone, so was his system.

Nelson was the soul of history in 1805.

The whole passage from Southey is splendid. “Early on the following morning he reached Portsmouth; and having despatched his business on shore, endeavoured to elude the populace by taking a by-way to the beach; but a crowd collected in his train, pressing forward to obtain a sight of his face: many were in tears, and many knelt down before him and blessed him as he passed. England has had many heroes; but never one who so entirely possessed the love of his fellow-countrymen as Nelson. All men knew that his heart was as humane as it was fearless; that there was not in his nature the slightest alloy of selfishness or cupidity; but that with perfect and entire devotion he served his country with all his heart, and with all his soul, and with all his strength; and, therefore, they loved him as truly and as fervently as he loved England. They pressed upon the parapet to gaze after him when his barge pushed off, and he was returning their cheers by waving his hat. The sentinels, who endeavoured to prevent them from trespassing upon this ground, were wedged among the crowd; and an officer who, not very prudently upon such an occasion, ordered them to drive the people down with their bayonets, was compelled speedily to retreat; for the people would not be debarred from gazing till the last moment upon the hero—the darling hero of England!”

Knight, Britain Against Napoleon, pp. 251-52, 260, 253

The Enemy at Trafalgar, p. 10

Knight, Britain Against Napoleon, pp. 253, 254, 255

The Enemy at Trafalgar, p. 8, 10

Knight, Britain Against Napoleon, pp. 278, 283

The Enemy at Trafalgar, p. 3

Victorious Century, p. 1

Terry Coleman, Nelson: The Man and the Legend, p. 6

Stephen Roskill, The Strategy of Sea Power (Collins, 1963), pp. 80-81

Rene Maine, Trafalgar. Napoleon’s Naval Waterloo (Thames and Hudson, 1957), p. vii

Becker, S. O., Hsiao, Y., Pfaff, S., & Rubin, J. (2020). Multiplex Network Ties and the Spatial Diffusion of Radical Innovations: Martin Luther’s Leadership in the Early Reformation. American Sociological Review, 85(5), 857-894. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122420948059.

Christopher Leslie Brown, Moral Capital: Foundations of British Abolitionism (University of North Carolina Press, 2006), pp. 197–200.

I recently subscribed to the Common Reader. Your Trafalgar Day post alone is worth the price. Thank you.

Great piece. Maybe your best!