How English prose made progress

my piece in the new edition of Works in Progress

In the first print edition of Works in Progress, I have a long piece about the history of English prose. It is now free to read online. (You can also buy a print subscription. They have beautiful design work done by Atalanta Arden-Miller.)

There have recently been many claims that modern prose is better because it is simpler, and that simpler means shorter. (Such as here.) Short sentences are widely believed to be better sentences.

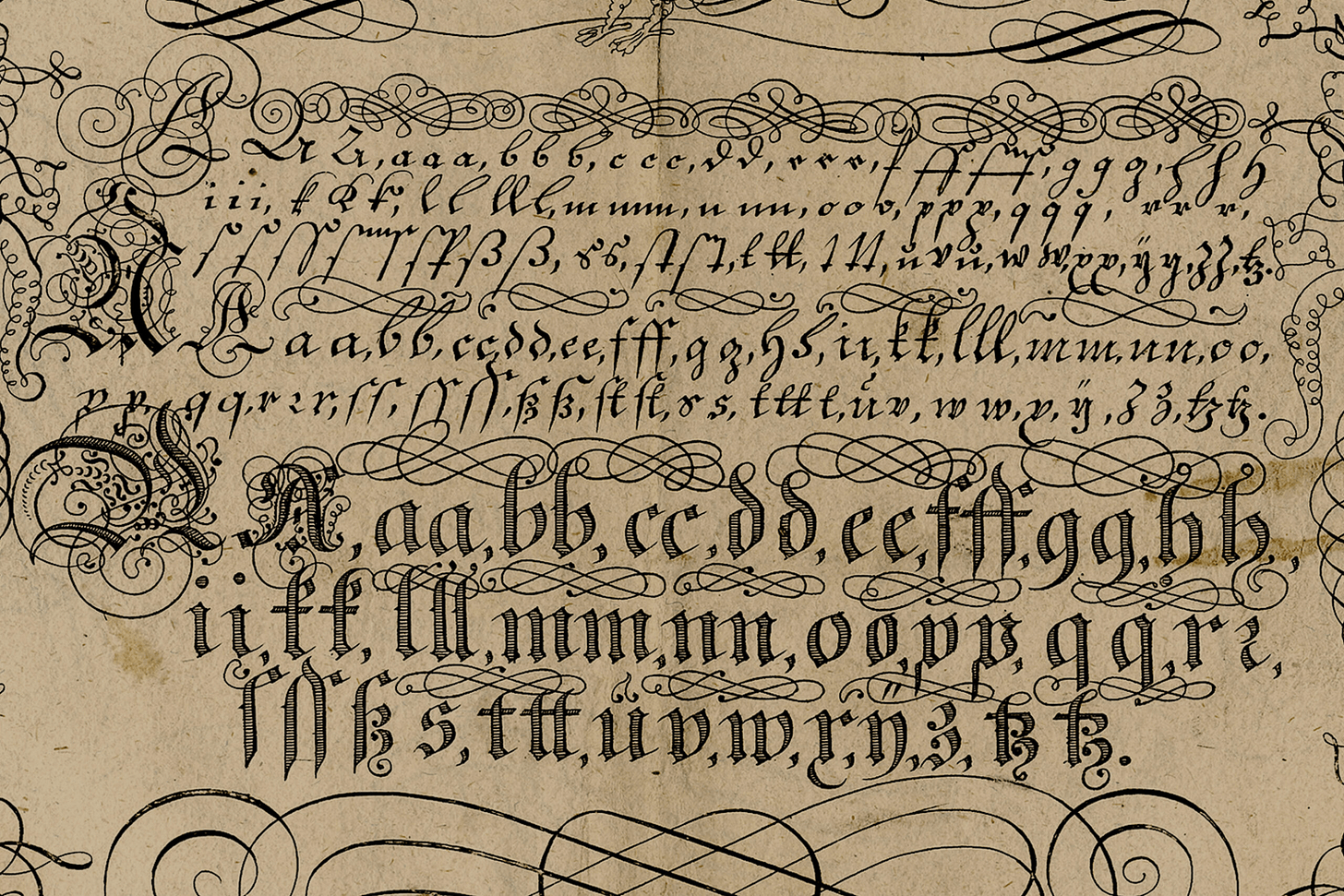

I offer a more complicated story of the history of English prose, to do with style and syntax. (Simplicity is about more than sentence length!) It’s a story that begins in the sixteenth century, rather than in modern times.

‘A sentence should not have more than ten or twelve words.’ VS Naipaul’s first rule for good writing is a popular one. From Hemingway’s legion of admirers, to Grammarly, to countless books and internet memes about writing well, the idea that shorter sentences are better is dominant. Many people go further, arguing that one of the most important changes in English over time is its sentences getting shorter.

This has been a standard modern academic account of English prose, from Edwin H Lewis’s 1894 book The History of the English Paragraph to recent dataset analyses. Arjun Panickssery recently argued that English sentences got shorter over time and that ‘shorter sentences reflect better writing’.

The Elizabethans and Victorians wrote long tangled sentences that resembled the briars growing underneath Sleeping Beauty’s tower. Today we write like Hemingway. Short. Sharp. Readable. Pick up an old book and the sentences roll on. Go to the office, read the paper, or scroll Twitter and they do not. So it is said. I would like to suggest that this account is incomplete.

I propose a different story. The great shift in English prose took place in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, probably driven by the increasing use of writing in commercial contexts, and by the style of English in post-Reformation Christianity. It consisted in two things: a ‘plain style’ and logical syntax. A second, smaller shift has taken place in modern times, in which written English came to be modelled more closely on spoken English.

What this should demonstrate is that shortness is the wrong dimension to investigate. We think we are looking at a language that got simpler; in fact we are looking at one that has created huge variation in what it can express and how, by adding new ways of writing. Lots of English writing has got simpler through use of the plain style, sticking to a logical shared syntax, especially the syntax of speech. But all the other ways of writing are still there, often showing up when we don’t expect them.

The rest of the piece looks at data-sets of sentence length (I’m skeptical!) and has examples of English’s changing prose from Cranmer to Substack. As well as Tyndale and Coverdale, Badgeot and Joyce, Smith and Mill, Dickens and Fordyce, I quote a range of writers like kyla scanlon, Rebecca Yaros, Astral Codex, The Villager, Alicia Kennedy, Matthew Yglesias.

In the Collects from the same prayer book, Cranmer starts writing complex sentences.

Lord, we beseech thee, assoil [excuse] thy people from their offences; that through thy bountiful goodness we may be delivered from the bands of all those sins, which by our frailty we have committed: Grant this, &c.

He had to write complex sentences to be able to translate the Latin faithfully. Cranmer punctuates logically, not for breaths or periods, but for the sense of the whole. This is the emergence of the fully syntactic sentence.

His sentences are clauses structured around finite verbs (i.e., a conjugated verb in a tense, not an infinitive: ‘we beseech’, not ‘to beseech’). In the example above, ‘we beseech thee’ is the main clause and ‘Lord assoil thy people’ is part of the object (the object complement). The rest are subordinate clauses. Notice that this is right branching, the subordinate material coming after the main verb. It’s the same sort of structure we might still find in the New York Times today.

My thanks to the excellent Julianne Werlin for her guidance (her Substack is Life and Letters), and to the remarkable book The Establishment of Modern English Prose by Ian Robinson, which I cannot recommend highly enough. My thanks too to all the editors at Works in Progress and everyone else who puts the magazine together. I am delighted to have written for them. I love reading their work, the design by Atalanta Arden-Miller is splendid (see below), and they take so much care over every detail.

I have just taken out a print subscription! Looks like a wonderful publication. I am surprised to see you sceptical with a 'k'.

Looking forward to reading this! It was about this time a few years back that I enjoyed reading another text in that publication about English style and how it's changed over time: “The Elements of Scientific Style” by Étienne Fortier-Dubois. It also addresses Plain English and is worth reading.