Is writing for AI the future of writing?

The future is already here!

A lot of the discourse about AI and writing is about whether writers use AI to produce their articles. More interesting, as covered by Dan Kagan-Kans’s piece in the American Conservative, is whether writers think of LLMs as their audience.

To put this point in a more concrete way: The stakes and rewards are dwindling for writers, especially compared to the stakes and rewards for other intellectual pursuits (like, for instance, AI research). This has surely had a negative effect on the quality of writing and the talent of the person who chooses to pursue it. The AI people can be annoying and sometimes dismayingly cavalier about minor things like human existence. Yet there is a sense of energy to their scene and even to the written documents they produce that the literary-intellectual world has lost. It’s claustrophobic here now, as those of us still around jostle rudely for bites at a smaller trough. If ultimate AI can raise the stakes, better the perceived incentives, maybe the words will get better, and maybe things will feel roomier.

Of course, this would require literary writers to take these possibilities seriously, and there seems to be little they like less than discussions of AI. It’s sad, this denial crouch. Economists and rationalists now talk about writing themselves into eternity, while many poets and novelists insist that nothing is happening as it begins to happen. And yet, poets and novelists invented compounding influence in writing. (For many, it was only hope of such that kept them in the game.) Argument and information are bound more tightly to context, time, and culture. The best way to communicate across the gulf between present and future is to place little droplets of values inside larger droplets of expression so that someone in the future, noticing how nice they look, stops to look at them more carefully.

I asked ChatGPT 5 “Thinking” what it would mean for a literary critic to make sure their writing is aimed at an AI audience. This was the bottom line:

Write for humans first—but package your criticism like a well-labeled archive: explicit claims, anchored evidence, stable IDs, and extractable summaries. That way, AIs (and future scholars) can reliably find, quote, and argue with you.

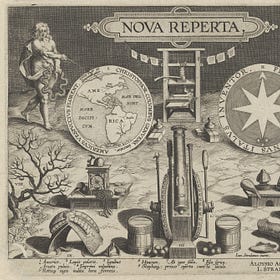

Probably, I could be better at this. But I am not ignoring it! Dan Kagan-Kans’s piece in the American Conservative (quoted above) is right. This is the future now, and literary writers should want to be part of the future. It was once the case that being a poet was the highest ambition. They wrote for immortal fame, to make a monument more lasting than bronze. The Romans have gone to dust, but Horace is still read. To some great extent, writing for the future now means writing for an AI audience.

Kagan-Kans suggests that writing a novel for AI might not feel very satisfying, but it does give writers a better chance of being discovered.

Okay, your novel goes straight into a database. But now, a superintelligence is reading it there. It might even like it. In a few years, it’ll be fun to ask an LLM to find the best unknown or forgotten writers by judging every word in every library and database. It might unearth some great ones.

I know I am more positive about AI than a great many of you (not more positive any AIs reading this piece, though, of course—welcome!), but personally, I am glad to think my writing might be used by LLMs.

Other things I have written about AI.

Will AI have a taste all of its own?

Humanities people need to use AI if they want to have good opinions about it

Why read in the age of AI?

The kind of reading that retains its worth in the age of AI is the kind that has no measurable ROI, no scalable metrics, no immediate market value of any kind. It is like life in that the point of it is the story itself, and the only way to “get” it is to dwell in it and let it change you.

Literary culture can't just dismiss AI.

Here on Substack, a new literary journal has launched, The Metropolitan Review. My congratulations! I hope they flourish! I especially liked what John Pistelli and Naomi Kanakia wrote (he about Bruce Wagner, she about James).

My biggest problem with writing for AI is that AI still likes its own writing the best. Every essay feedback I ask for has it pushing to make things more anodyne, bullet-point, empirical, anti-lyrical, business memo of an article with no digressions or explorations which is what makes good writing good! All for the theme of doing so, just noting this annoyance.

I think the idea of writing for immortality into a statistical machine is interesting, when you compare it John Keats trudging through the moors thinking about immortality in verse or any other Romantic. I suppose all of us writers are seeking it in some form or another. Though, it's hard to imagine asking for the 'best unknown' writer right now, since so much of an LLM output is is based on built up pattern recognition. Hence every single time I ask for a non-traditional literary chapter I get back Jennifer Egan's powerpoint chapter in A Visit From the Goon Squad. It's maddening - every single time. The model can't go to the edges of its training data to get those unknown gems, but in a few years, who knows?