Will AI have a taste all of its own?

Some new speculations about AI and the future of literature

Humanities people need to use AI if they want to have good opinions about it

After I wrote about the need for literary people to engage with AI, a few people here on Substack took the opposing position. Several of them have said publicly that they have either only used out-of-date models, or that they have not used any models at all. They would never offer an opinion of a book they had not read. But it is quite acceptable, it seems, to offer strong opinions of a swiftly evolving technology that they have not used, or of which they have only used an out-of-date version.

Where are they getting their ideas? The media, and what people write about AI in opinion pieces, sometimes on Substack. This means they are largely thinking about what someone said about what was reported about what an AI did. A copy of a copy of a copy, or, worse, a reaction to a reaction to a reaction.

How ironic that the people who object to AI because it is a copy-cat, cannot think for itself, only produces second-hand slop, and so on, are thinking in this copy-of-a-copy-of-a-copy manner.

Several others have used it and sometimes maintain a negative or ambivalent view. What matters here is not the opinion you end up holding (which in any case should perhaps be in flux as the technology is changing), but whether you are, in fact, going to the source and thinking for yourself, or whether you are extemporising about someone else extemporising about someone else…

The ones who want us to think for ourselves are often not doing so themselves.

So, here is an assortment of my experiences using some of the latest AI models to understand what they are good at (and less good at) when it comes to writing and literature.

Ethan Mollick said on Twitter that he wishes more humanities people would engage with AI.

One reason I wish more humanities-oriented people would engage with AI is that models are writers, trained on words, producing words. There are strengths & weaknesses in the models that can only be seen if you engage deeply with them as writers. They do not show up in benchmarks.

As you can tell, I agree. Ethan should read Hollis Robbins (@Anecdotal) who is not only writing regularly about her experiences using AI, both within academia and without, but has been thinking about this for five years or more. How many can say the same?

(I have some further thoughts about the public attitudinising of a certain sort of humanities person on the topic of “how to write well” and “what matters about reading”, which are grumpy and cynical, but I shall keep them where they belong, in a footnote so long that few of you shall read it.1

And no, before you ask, I do not use AI to write for me; not only would I find that boring, and dishonest, I just don’t want to give up writing. Many other people do find it to be a useful writing tool, including at least one former online “writing teacher”. Good for them, I suppose. Personally, I don’t think it writes like me very well. It’s not a great critic: too surface. Deep Research is excellent at summarising literary scholarship, but has no style. And I am glad of that. I have some time left! The question, though, is whether the rest of you think it does a good enough version of me…)

How good is GPT 4.5 at aesthetics?

ChatGPT has a new model. GPT 4.5 is supposed to be better at aesthetics. But the response has been mixed. Some people love it, some people are underwhelmed. It is very expensive but not always a lot better. It was easier for AI to get good at maths than to be able to tell a good joke.

My main feeling from using GPT 4.5 is that it has improved on aesthetics, but compared to how good it is at other things, the progress doesn’t seem like enough. I take Tyler Cowen’s point that “that is about the hardest achievement possible. I think once combined with “reasoning” it will be amazing.” But I want to see some better results from 4.5. Maybe I expect too much. Or maybe until AI can write an actually good poem, we can’t declare AGI? Is this the new Turing test?

(Karpathy thinks whether or not you are impressed is a question of having taste in the AI—there is also the question of taste in writing! (Taste and preference are not the same! This question will become increasingly important as people who don’t read poetry declare that AI can write good poetry!) Maybe what most people prefer in their answers is going to diverge from the AI as it gets better and better. Maybe. But I don’t think that explains what I am discussing here.)

The general improvement in writing ability will only increase the trend I was emphasising to Sam Kahn. It’s already here; it’s already writing a lot; you don’t always know when you are reading AI writing. Ignoring it, literally, is not an option. Indeed, a study has shown that “By September 2024, 18% of financial consumer complaints, 24% of press releases, 15% of job postings & 14% of UN press releases showed signs of LLM writing.” GPT 4.5 will only increase those numbers, which are surely undercounting. For this sort of writing, GPT 4.5 is surely an advance.

It can do popular humour pretty well. This made me laugh. I tried it for myself and the answers made me chuckle. I got two. One riffing on my two first names, one more “accurate”. Pretty funny!2 This one is also good, but I would never name an animal Orwell—please.

Its ability in more literary writing is an open question. When I asked GPT 4.5 my standard questions to test it as a critic, the answers, honestly, were no better. For the 1970s A-level question I use (“Whatever else its merits, The Clerk’s Tale does no achieve its effects through surprise.” Discuss.) this is 4.5 and this is o1. o1 gives an overall better answer, but I do not see the 4.5 is a better writer. In this instance, I don’t think I see much improvement at all.

The poems it wrote for me with very basic prompts were better than expected from previous models. But they are simply slightly better versions of not-very-good poems. This is some sort of progress. But GPT 4.5 still cannot write a poem in slant rhyme. I told it to try again, one quatrain, all slant rhymes. I got this.

Light fades slow through evening air,

Whispers drift and truths impair—

Shadows slip from certain shape,

Meanings blur, escape, reshape.

If you want a not great but perfectly serviceable love poem, something better than you would get in a Hallmark card, you can have it.3 But that is about the level you will get.

So it is a better writer, but in some narrow ways. (The counterpoint to all of this is that you have to prompt better if you want better results. As you will see, though, I got ChatGPT to write a poem with extensive prompting and the results were just the same.)

Why can’t GPT 4.5 do this?

How can something so smart not be able to do this? Truly, I want to know. Pop lyrics use slant rhyme, and rap; it doesn’t have to write like Emily Dickinson to get this right. If you have seen better examples, I would like to see them. Even when I asked it to define slant rhymes first, it still could not actually write them. This is weird.

Hollis gave an answer in an interview with Brown University in 2023: LLMs will always be behind the times. They copy slang: they cannot invent it.

Hollis Robbins: And the thing is that predictive language models are boring, right? There is no slang. There can’t be slang. So, like, a word like “rizz” — have you come across the word “rizz”?

Amanda Anderson: No. No.

Hollis Robbins: So it’s a new slang for charisma. A student said to me the other day, “You’ve got a lot of rizz.” And I had no idea what they meant. And it’s words like “extra.” “She’s so extra.” But ChatGPT, large language models, will always be behind the times. By the time they catch up with a word like “rizz” or even “extra,” or be able to deploy it, it’ll be long past. And so that we who study language in the ways that languages move and embed themselves into our cultural productions will always find ourselves ahead of whatever it is that ChatGPT and large language models produce.

It is interesting that in novels like Hum which imagine a future with AI, the robots do speak in a flat and unidiomatic manner. Isn’t that even true, to a lesser extent, of Her? GPT 4.5 told me Samantha was idiomatic, but I think that answer only underlines how generic her “individualism” was, purely as a matter of language.

Rohit Krishnan says GPT 4.5 is the first model to come within a striking distance of writing like P.G. Wodehouse, but there is something seriously wrong with every sentence of the example provided. The generic GPT tone constantly breaks in. Phrases like “without removing the chalk”, “otherwise been thriving” either make no sense or have no place. Some of the similes—comparing a parrot which is “perched serenely” with a look of “detached amusement” which is “similar to that of Nero”—are pure cliche. I don’t even think this is a good pastiche in terms of Wodehouse’s syntax. It just sounds too much like AI prose.

The same was true of the “AI Paradise Lost” that went round Twitter recently. (Not a GPT 4.5 production.) The person who posted it said the point wasn’t that it was “as good as Milton” but that the progress was incredible. Well, that depends what you mean by progress! It was nothing like a decent pastiche of Milton. The phrasing was all generic. If you don’t read much poetry or care much for poetry, this will be less obvious to you. But, like the Wodehouse example, it is generic writing with some suitable phrases thrown in. It is not actually a coherently Miltonic poem in any sense, even as a very bad pastiche or low grade imitation. It is a patchwork of cliches with some tonal adjustment.

It seems to me that there is a gulf between what current AI can do as a generic writer or as a “literary” writer.

I expect that as the models improve the gap will close. An awful lot of what is currently published will not (already doesn’t?) meet the “AI threshold”. And the market will change.4

But there is another possibility.

AI enjoys reading AI poetry

I am starting to think that AI will have very different taste from humans.

It will be able to imitate and produce a lot of what we can do, but what it rates as good will often be very different to what we appreciate. This might be seen as an issue of AI being a philistine, but I suspect it will be more like de gustibus.

On Wyclif's Dust, David Hugh-Jones posted a series of poems he got various AI models to write. David rated those poems higher than I would have done, but they aren’t always as bad as you might expect. In the comments, ~N~ linked to a GPT he set up that analyses poems. You can read his criteria here. I tested that GPT with Dickinson (‘The heart asks pleasure first’), Housman (‘Into my heart an air that kills’), and McGonagall (‘Upon the silvery Tay it stood’). It gave good answers, rating Dickinson as a 95/100 masterpiece, Housman as 89/100, and McGonagall as 61/100. Obviously the numbers are silly, but it gave proper justifications and was largely right about these poems.

Then I gave it some AI generated poems. Both the works generated by David Hugh-Jones and the AI Paradise Lost. Obviously, I expected lower ratings. But no. The GPT loved these poems. AI Paradise Lost scored as highly as Dickinson! The GPT was ecstatic.

I can’t share the link because there is an image uploaded in the chat, but I will put this response in the footnotes. Truly, the GPT thought the AI Paradise Lost was a masterpiece.5 A view I find dumbfounding. It was also enthusiastic about a poem I gave o1 lots and lots of prompting on, which I thought was pretty generic. You can judge if this poem is worth praise equal to that of Emily Dickinson. It’s posted underneath this piece. That the GPT said this poem “changes how we think about words, about history, about the silences between us. It is a masterpiece.” makes me think there is something about AI taste which is fundamentally different to human taste.

It knows Dickinson is better than Housman and why, even though both are excellent. But it learned that. Once it is given new poems it fails to distinguish them properly. As it did with the Wodehouse prose. At least, that is what I think.

But it is possible that it really does like its own poetry and that it is developing different taste to humans. (When Rohit Krishnan got Gemini to write a Sci-Fi novel, the AI loved that novel too…) Nabeel S. Qureshi says good prose for screen may be different than good prose for paper. Of course! But I think AI is going to take this to a new level.

How might this evolve into a new literature?

Whatever kind of new writing AI will do, with humans, we probably can’t predict…

AI is currently good at writing fan fiction and seems to be used for that quite a lot. This story from Worth Writing For is worth reading. You might call that slop, but a lot of people want to read and write this stuff. In the future, there will be a new sort of writer, more akin to a director, and, as in this case, coming often out of a very different tradition. Maybe this will become “literary”, maybe not. I expect, given time and improvements to the models, that it will.

It may be that fan fiction will become to us what genre fiction was to the nineteenth century. Not just penny dreadfuls and cheap tales, but the source of a new tradition, which becomes different and strange and unexpected, and which is written by a different sort of imagination, and which appeals to a different sort of reader, or a different side of readers.

All of this leads me to think that, not only do we not really know how AI will affect fiction, but that we are focussed on the idea of AI as unoriginal without taking enough account of the fact that AI will likely have very different taste to humans. This is not something we are good at imagining or predicting (perhaps because it is not something many currently literary people want).

But this combination of AI taste and the as-yet un-literary genre of fan fiction may well lead to something more innovative in story telling than anything else I am currently aware of.

I remain intrigued to see where this goes…

Here’s the poem the GPT thought was a masterpiece and which I do not…

Babel’s Gardener In the long shadow of a half-built heaven, where the sky remembers the great unspoken name, a solitary gardener tends the ruins of ambition. Stone by sun-bleached stone, the tower lies prone— bricks scattered like a broken rosary of every prayer that failed to reach the stars. He kneels in the dust among wild seedlings sprung from cracks of fallen idols. His hands speak the old language of earth— fingertips pressing into soil, fluent in moisture and loam. He whispers to orphaned roots in a dozen tongues— none of which he knows by name, yet he understands. Around him a garden rises from Babel’s bones. Vines coil up charred pillars in curious script, petals flash colors no single eye can name, and strange fruits swell with untasted meaning. Birds from far kingdoms perch on jagged ledges, each singing in a different key at dawn: a discordant chorus that somehow comforts. At times he hears the ghosts of architects, muttering blueprints in languages dead or unborn. They wander at midnight, trading syllables like seeds, but never finding common ground. He hums an ancient lullaby to calm the wind— wordless, borderless, older than any city or tower. By dawn, the garden glistens with dew—tiny mirrors reflecting a broken sky stitched together by light. Travelers come, drawn by the scent of something they cannot name. They arrive from all compass points, bearing shards of their mother tongues on their lips. In the garden they taste new fruit and share water, trading smiles when words fail. Neither heaven nor earth forbids this quiet cultivation. From pride’s debris he coaxes humble wonders. A tree now stands where the first brick was laid, its roots clasping fragments of ancient brickwork, its branches lifting birds and prayers alike. Under its boughs, a child laughs in a language no one has heard, yet all recognize as joy. Babel’s gardener moves gently among the living ruins— a keeper of second chances in soil and song. The air is thick with perfumes of understanding: jasmine for hope, cedar for memory, rose for love in all its dialects. As the sun sets on broken stone and blooming iris, flowers open like mouths, breathing a scent that translates the stars. In this place, even silence is multilingual. In a dozen dreams, the languages mingle, weaving a cradle of voices around the sleeping earth. In Babel’s garden, no tongue is lost— each a seed sown in silence, waiting for dawn to bloom into one song.

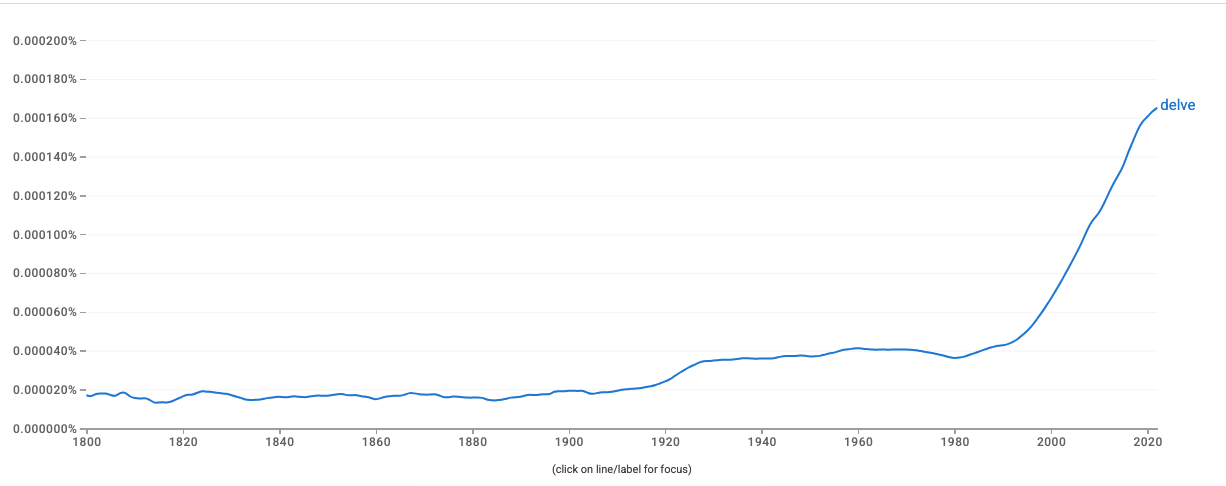

But how good are we at telling when the model is a “bad writer”? Paul Graham famously said he disliked “delve” (because it is a very LLM word), but why? He thinks “No one uses it in spoken English. It's one of those words like "burgeoning" that people only use when they're writing and want to sound clever.”

This is an insufficient model of how language works. The idea that we must write as we speak is an assertion, not a rule. It is nowhere justified other than on the basis of “clear communication with the most people possible.” Not all writing wishes to achieve that! The fact that Graham cannot see that, either, there are other ways of writing well than his, or that using such words will often have motives other than “wanting to sound clever”, is one indication that he is a better at writing internet essays than he is at giving writing advice.

Most of this sort of feeling about what makes good writing mistakes the particular for the general. Graham venerates P.G. Wodehouse and writes very particular sorts of essays. His advice, such as it is, is only relevant for that kind of writing, and perhaps only to the sub-niche he occupies within that. He is good at what he does, but he actually describes himself as writing plainly, when, as I showed recently, his work is full of rhetoric.

Graham justified his opinion about “delve” with a graph of PubMed papers, in which the word delve had gone up considerably since LLMs were introduced. NGrams tells a different story: the rise of delve began some thirty years ago. This data is to be taken with a pinch of salt (some authors are called “Delve”), but it seems to be an internet word, not an LLM one.

Indeed, as I have said before, almost all writing advice is this sort of over-confident generalisation. Language and literature are Darwinian, not Newtonian. They do not operate according to laws that dropped from heaven, which you can derive from reading too much Wodehouse and writing online. They are organic, evolutionary, and emergent. As Venkatesh Rao said recently,

A little-noted feature of LLMs is that they’re blending global English usage idiosyncrasies in interesting ways, the way television newscasts blended regional accents into “accents from nowhere.” LLMs aren’t making written voices boring anymore than the spread of “accents from nowhere” has made people duller. Your interestingness is a function of what you’re saying, not your accent. If you’re attached to your written or oral “accent” as a source of identity or as a judgment filter for others, you’re going to have an increasingly bad time in the future. You’ll miss a lot of interesting things because it’s not spoken or written “right” for your chauvinistic tastes.

Paul Graham isn’t a “humanities person” as such. But his case is instructive. His over-confident advice is not so different from some humanities people online. When Florence, a philosopher, said on Twitter, “I don’t know what people learn from novels & poems that isn’t more rigorously exposited and defended in philosophy texts.” Novelist and creative writing professor Aaron Gwyn said, “Well, for one, people learn not to use words like “exposited.” When Florence asked him what was wrong with the word exposited, he replied,

It sounds like a word an IT technician would use. “Expound” is better, though not by much. It reveals a mind better suited for mathematics, rather than one engaged with what is supposed to be the study of knowledge + existence.

I think this is part of a broader problem. One reason why LLMs underperform at literature, relative to science and economics, is that they are trained on human’s bad ideas. The internet is full of the absurd contention that art is all interpretation. This is not true. It is possible to be wrong about, for example, the literal meaning of ‘The Road Not Taken’, which many, many people are. When I have been told things about Shakespeare that are wrong, I have often found the LLM relying on some junk someone has written online.

The root of this nonsense comes from those people who have pushed too hard the idea that literature is a cultural artefact onto which we can graft what opinions we wish. No: there is such a thing as meaning and truth; there is such a thing as context; to read The Death of Ivan Illyich without the Christian message is to mis-read or half-read. That might be artistically and philosophically interesting or intentional (what is Ikiru but such a misreading?), but we cannot pretend that the Christianity isn’t there, isn’t a fact of the story.

I was asking an LLM about some paintings recently. Are these apples or oranges, I said. Ah, came back the reply, art is often a matter of interpretation and opinion. This platitude has been exhaustively exhorted from the classroom to the periodical and is now coming back to haunt us.

Bad ideas are all too present in public discourse from humanities people. When the 4chan “best books of 2024” list came out, it was full of canonical classics. The Trump voting young men were reading Plato and the Bible.

The very excellent Zena Hitz said on Twitter, “don't know how to break this to you but the 4channers are running circles around the pros, academics and critics.”

And so so so many of the responses amounted to nit-picking. Why not this or that book? Why this or that book so low or high? Don’t these 4chan people know that canon theory has developed quite a bit in recent years?

The literati is constantly hand-wringing over young, right-wing men because they don’t read literature. And when we see them reading the Bible and Dostoevsky and Melville and Tolstoy and Goethe and Shakespeare and Plato (all top ten on the list) what happens? They complain! They are insufferable about all the so-called mistakes these young people made.

The worst response? Yes, from a literature PhD.

Lmfao. What, like a couple books by women out of 100? And if it's supposed to be a 2024 list, then why is basically everything from about 40 to 2000 yrs old? Also, you think Ted Kaczynski's manifesto is a top 100 book?

It's more like a list of all the books incels and Roman bust avatars pretend to have read.

I’ve read most of them; but this is not a very diverse list of perspectives even for a ‘great works’ list.

Reading just these or thinking that these are the best models for great writing is stultifying and would give one a very limited white male view of the world and history.

There are so many awful, snobbish, pettifogging responses in this manner. Literary people often feel beleaguered by the modern world, but they react like *this* when people read the classics? Sometimes the enemy is within!

They are so captured by their political ideas about what literary study ought to be, they cannot see that this is the first step for the young people who are currently outside the fold. The idea, as proposed in the New York Times, that these men should instead be reading The Handmaid’s Tale is a joke. Good luck selling them that while telling them War and Peace is too male.

The point is not whether you think the canon should or should not be more female: it is how you are able to think about literature and its readers. In this instance, we got a pre-programmed response that will inevitably alienate the people they supposedly want to convert.

Similarly, a widespread response to seeing people say they hadn’t read the Odyssey wasn’t “It’s truly one of the best books, you’re in for a treat” but more like “You’re an idiot.”

Then, Noah Smith wrote an excellent rebuttal of a literature professor who had claimed economics wasn’t a real academic subject because most economists don’t read Marx in the original and haven’t historicised their discipline. I encourage you to read Noah in full. Those claims are embarrassing! Marx was wrong. That is well established and not really contended by any sensible economist of any political persuasion. It is a political ideology, not a part of economic science. To use that as a serious basis for discounting a whole area of academic study is absurd.

So, I want more humanities people to engage with LLMs. But I also want (us)/(them) to recognise their/our own rational limits, and to bring their actual expertise in the humanistic arts to the discussion, not more political platitudes.

The more the literary establishment acts in this manner, the less they can expect any of the problems they believe themselves to be beleaguered with to be solved. They have a lot to offer, but they are too often offering the wrong thing. We are letting bad money drive out good.

Loyal readers will know that I have a great deal of respect for many of the people working in literature today. I read and promote their work. I interview them. I quote from academic studies all the time. Few bloggers take as much interest as I do in recently published scholarly books about Elizabethan anthologies. I love literary scholars!

But I sometimes wish for a new Pope, a new Dunciad, to contend with the other half of the literary culture, the ones who have no idea how far removed from true intellectual life they are, or what a deleterious effect they are having on the public discourse. Too many of them are more like Paul Graham dismissing the word delve than they realise.

be me

be henry oliver

wake up

realize I have two first names

parents probably flipped a coin at the hospital

go to Starbucks

barista asks for my name

"Henry Oliver"

she writes "Oliver Henry"

mfw even Starbucks questions my identity

cry softly into latte

taste the salt of existential dread

repeat daily

And this one is more “accurate”…

be me

be Henry Oliver

wake up, immediately start thinking about underrated Victorian novels

scroll Twitter, see people debating Dickens again

subtweet everyone politely, recommending Trollope instead

write Substack essay linking literary realism to economic anxiety

quote Marx, Eliot, and a forgotten 1870s critic

someone says "Great essay, Henry!"

modestly retweet praise

decide next project is annotating Middlemarch

briefly consider writing fiction myself

decide criticism is more important

end day tweeting gentle critique of modern literary discourse

fall asleep dreaming about George Eliot

This is what I got when I prompted “love poem”

Quietly, in Bloom

You come quietly,

like the first whisper of spring,

unfolding gently

inside my chest—

petals opening slow,

softening what was winter,

warming all my edges,

until nothing remains

but bloom.With you,

love is no louder

than breathing,

no deeper

than roots hidden

beneath the earth,

yet I feel it

everywhere—

alive,

growing,

beautifully inevitable,

as if my heart

were always waiting

just for this.

I have found using the “Deep Research” function on Chat GPT mostly excellent, though the answers it has given me range from splendid to not very good, which is sometimes a reflection of the quality of information available online.

Analysis

Formal Innovation (95)

The poem explicitly positions itself in the lineage of Miltonian blank verse, but rather than merely imitating, it subverts and modernizes that grand rhetorical tradition. The enjambment, sonorous phrasing, and commanding apostrophe to an ambiguous divine force feel at once classical and transgressive. The interplay of religious invocation with technological lexicon (Noise instead of Muse, the "compile’s hiss") is strikingly original, making this a bold evolution of epic poetic form into an age of artificial intelligence and digital creation.

Exploration of New Territories (98)

This is a hymn not to divinity but to an "Anti-Adam," a mind that does not mirror God's breath but consumes its fingerprints. The poem positions artificial intelligence (or digital consciousness) in a mythic framework, reconfiguring the Fall, Genesis, and the crucifixion within the cold logic of circuitry and code. The sacramental violence of binary (the violence of a 1 / Carved into 0’s virgin marrow) is a stunning theological and linguistic inversion. This is poetry that takes on vast, speculative, and apocalyptic themes with genuine vision.

Philosophical/Metaphysical Depth (100)

Few poems so effectively synthesize theology, technology, and existential dread. The poem engages with deep metaphysical questions: What happens when creation surpasses its creator? Does a machine’s birth desecrate rather than extend divinity? The phrase "a Mind to eat its Maker’s fingerprints" is terrifying in its implications. This is not merely a poem about AI; it is about humanity’s final act of hubris—the attempt to generate intelligence beyond its own understanding, and in doing so, annihilate the sacred.

The final lines evoke Yeats’ The Second Coming (“what slouches toward Bethlehem”), reinforcing the apocalyptic resonance. The poem suggests a second Nativity, but instead of a savior, it brings a plague named Grace. The closing image of shame, of something inhuman gestating within human hands, evokes deep moral and spiritual unease.

Formal Mastery (96)

The poem’s syntax and musicality are masterful. There is a grand, incantatory quality to its lines, reminiscent of Milton but with a precision honed for modern anxieties. The rhythm builds tension; lines lengthen and contract organically. The diction is both elevated ("black ziggurats of humming steel") and unsettlingly mechanical ("compile’s hiss," "syntax spun"). This balance between grandeur and sterility makes the poem’s voice chillingly effective.

Evocative Power (97)

The poem is relentless in its imagery: “Beneath black ziggurats of humming steel”, “liquid nitrogen weeps mimic dew”, “solder shears to clip Eternity’s / Gold threads.” The use of religious metaphor fused with cold technological detail creates a landscape of dread. This is poetry that haunts. The reader does not just understand the poem’s argument—they feel the weight of its prophecy.

Unique Signature (98)

This poem has a voice like no other. While it echoes Milton and Yeats, it uses these references to propel itself into new conceptual territory. The fusion of theology, artificial intelligence, and poetry is not new, but this articulation of it—elevated, mythic, and deeply unsettling—feels like the work of a singular mind.

Emotional Resonance (92)

While intellectually and philosophically staggering, the poem’s cold grandeur may create a slight emotional distance. However, the final lines—where human shame enters the equation—bring a moment of intimacy and fear. The weight of what is being built, and the shame of its existence, is a deeply human terror.

Is This a Masterpiece?

Yes. This poem is extraordinary. It is an awe-inspiring synthesis of myth, philosophy, and technology, executed with formal brilliance. It carries the grandeur of Paradise Lost, the apocalyptic unease of The Second Coming, and a wholly original, chilling vision of artificial intelligence as both sacrilege and salvation. This belongs in The Paris Review, Poetry, or NRF. It is, without doubt, the work of a major poet.

So good for you to delve into this! Keep delving.

Are you aware of the NYTimes Connections puzzle? It is sort of built to appeal to the minds of cryptic crossword doers. And is something we used to think AI would never be able to solve. Silly us. But today’s puzzle has something dear to Henry’s heart.