Life on a Leash

The chilling spirit of the petty bureaucrat is everywhere and waiting for its chance.

A special post this weekend, written jointly with Rohit Krishnan whose Substack Strange Loop Canon I highly recommend to you all. Rohit’s essay about the East India Company is one of the best articles I have read on the topic of autonomy in corporate life. This is something I know about from my day job—and it’s relevant to the topic of talent more generally, which is what my late bloomers book is about—and it’s something Rohit knows a lot about from his work, so we decided to collaborate on an essay.

Our main thesis is this. Productivity relies on the proper flow of information in a business, but that can also restrict autonomy and reduce initiative. In our experience, and based on some external evidence, there’s reason to think autonomy might be on the wane in corporate life. We live in bureaucratic, sludgy times. This essay looks at the history of org. charts, the East India Company, Bloom and van Reenen, and financial markets to argue that we need to encourage more autonomy in corporate life.

Enjoy…

Not that long ago, to take a job up overseas was a grand adventure. You’d have to jump on a ship and travel for months to a new land, with new peoples, often a new language, and you’d survive on your smarts and wit. When the US was considered the land of opportunity it was so that someone could reinvent themselves in the New World.

This isn’t how things work today. When Rohit worked at McKinsey, more than half his work was done on the move, in airports and hotels. Distance didn’t matter, and autonomy existed only in half-day long increments. The fact that you could speak to someone so easily (even in the days before video calls) meant that you did talk to your team often.

Henry consulted about marketing for global corporations. For a decade he interviewed or ran focus groups with people all over the world, in businesses ranging from small start-ups to Fortune 500 companies. People often talked about the benefits of global teams, extended networks, and new opportunities. But when asked what that meant for them in their jobs, the answer often came back—not much. Being at the periphery of a global business is often just that: peripheral.

In the past, the fact that you could course correct mistakes and iterate fast also meant that you did correct courses all the time. Corporate life today is often the death of autonomy as was practised for much of human history.

The idea of sending people ahead to do what’s in the best interest of the home-base was how things were done. The rulers appointed by Alexander and Genghis Khan had to do what they thought right. The Mandarins in China, armed with the knowledge from passing their imperial exams, were often posted in remote areas. The Indian Civil Service, even till recently, posted some of its young graduates in far-off villages where often as not they had to contend with local situations and deal in their own fashion. Same for banks. In the olden days of blood and Empire, the East India Company did the same, sending its employees to far away lands to do what’s best for the Company.

For instance the Company, once it started owning land, getting state appointments and engaging with the Nawabs in India, decided they needed court representation. But they of course couldn’t be full fledged ambassadors. And so they decided on a role called a Resident.

A Resident was effectively the cultural intermediary between the Company and the various Indian Raj’s they were with. They were knowledge conduits in both direction, had diplomatic duties both implicit and explicit, helped build bridges between the two people.

This level of responsibility is of course easily described in large, handwavy sentences, and impossible to describe in any meaningful detail. But the impact is extremely clear, whether that’s in identification and building of new ports, identifying new trade cargo and routes, or currying favour by lending their army to expand their empire.

A manager today is not just responsible for doing the job she was hired to do. She’s also responsible for continual enforcement of rules from above, ensuring a steady stream of information moves through her in all directions—down, up and across. She is less an autonomous entity than a node in a vast information network.

In 1957, the American sociologist William H. Whyte published a book called The Organisation Man, arguing that American corporations had given up hiring creative individuals, stopped prioritising new ideas, and were intent only to manage rather than lead. The Organisation Man was a smash success, selling two million copies. Whyte was worried that the Protestant work ethic was giving way to corporate conformity. As C. Wright Mills said in his review, the premise was that “the entrepreneurial scramble to success has been largely replaced by the organisational crawl.” The new generation in corporate life lacked a sense of mission or purpose, they prioritised work life balance, and they thought that “human understanding” should take priority over brilliance. Something of this mood is haunting corporate life again today.

In his essay What Should I Work On? David Perell describes the dilemma of the millennial generation—desperate for purpose while pursuing conformity. This quote sums up the experience of so many people currently entering middle age.

Too many of our smartest minds are working on trivial tasks and spending their time in corporations where they feel invisible. The vast majority of my friends who work for big companies say they’re bored, unchallenged, and under-employed. They don’t see the tangible benefits of their hard work.

Looking like you’re being productive is often a better strategy for career advancement than actually being productive. That’s why extroverts without conviction, many of whom spend more time networking than executing, rise to the top of the corporate hierarchy.

Dissatisfaction is everywhere and talent is left to fester. Deloitte’s most recent Gen Z and Millennial Survey found large numbers who would consider leaving their job without another one lined up. Between two fifths and a half of them have rejected a job or assignment for ethical or “purpose” reasons. Only half of them feel empowered to enact change within their organisations but 89% feel a sense of belonging. The dissatisfactions of communitarian corporate life are evident in these numbers, even if they might seem whiny or entitled on the surface. It’s no wonder the interest in hybrid work and work life balance has been so high in a culture where people are disconnected from the ability to do meaningful work.

Everywhere you look bureaucracy is rising. In the nursing and teaching professions paperwork has ballooned. The legal sector has grown on a swell of new laws. Publishers are acquiring sensitivity readers. Tax codes are expanding. Even taking the train comes with a flurry of announcements about safety and reporting suspicious behaviour.

Plenty of consumer experiences have become easier in recent years, but so many are more complicated. In academia, the process for writing and submitting journal articles is fit for the Kremlin or the Vatican in its arcane delays. In Europe cookie consent boxes cumulatively waste hours of your life. Government forms are onerous. Corporate life is bureaucratic. The chilling spirit of the petty bureaucrat is everywhere and waiting for its chance. The legal scholar Cass Sunstein has proposed “sludge audits” as a way of simplifying this tide of time-wasting conformity.

Young people with high ambitions and bright dreams are entering professions bound up in red tape. You dream of awakening young minds or pursuing justice—you wake up to the burdens of lesson planning and pedantic procedure. Major corporations talk endlessly about autonomy and innovation but subject employees to long, boring, mandatory training about all manner of legal risks to cover their backs. HR departments are designed to find uniform methods of managing people rather than to empower managers to release potential. Look at the ridiculous reaction to Dominic Cummings’s attempt to hire “weirdos” to Downing Street. Why are we so upset by the idea of the unusual and the autonomous?

People feel that weirdos process information in a way that’s antithetical to existing social norms, even fragile norms. The weirdos’ value has increased because “normal” methods of processing information have led us to inevitable roadblocks and gridlock. Saying no is a superpower, and it’s always easier to just ask for more data or options than to make a decision. Even the idea that we want to see more “weirdos” is a reaction to the fact that “normal” methods of doing things inside organisations have been gummed up through the replacement of personal autonomy with impersonal bureaucracy and an incredible number of rules.

Many philosophers have had the famous dictum of treating people as ends, not means. There’s plenty of argument about what this might actually mean, like with most things philosophy, but one thought is that it means to treat people as if they’re full fledged beings, not mere automatons. You shouldn’t treat an organ donor as if she’s just an organ donor, but should think of her as an individual with their own life, which is sacrosanct.

There’s a countervailing force, which is prevalent in business and politics and generally areas of life that deal with working with other people, which is to use them to complete specific tasks. Like Henry Ford’s famously excellent idea of the assembly line, which removed individual agency in creating items with the efficiency and scale that comes with intense specialisation, this has had tremendous benefits for our society.

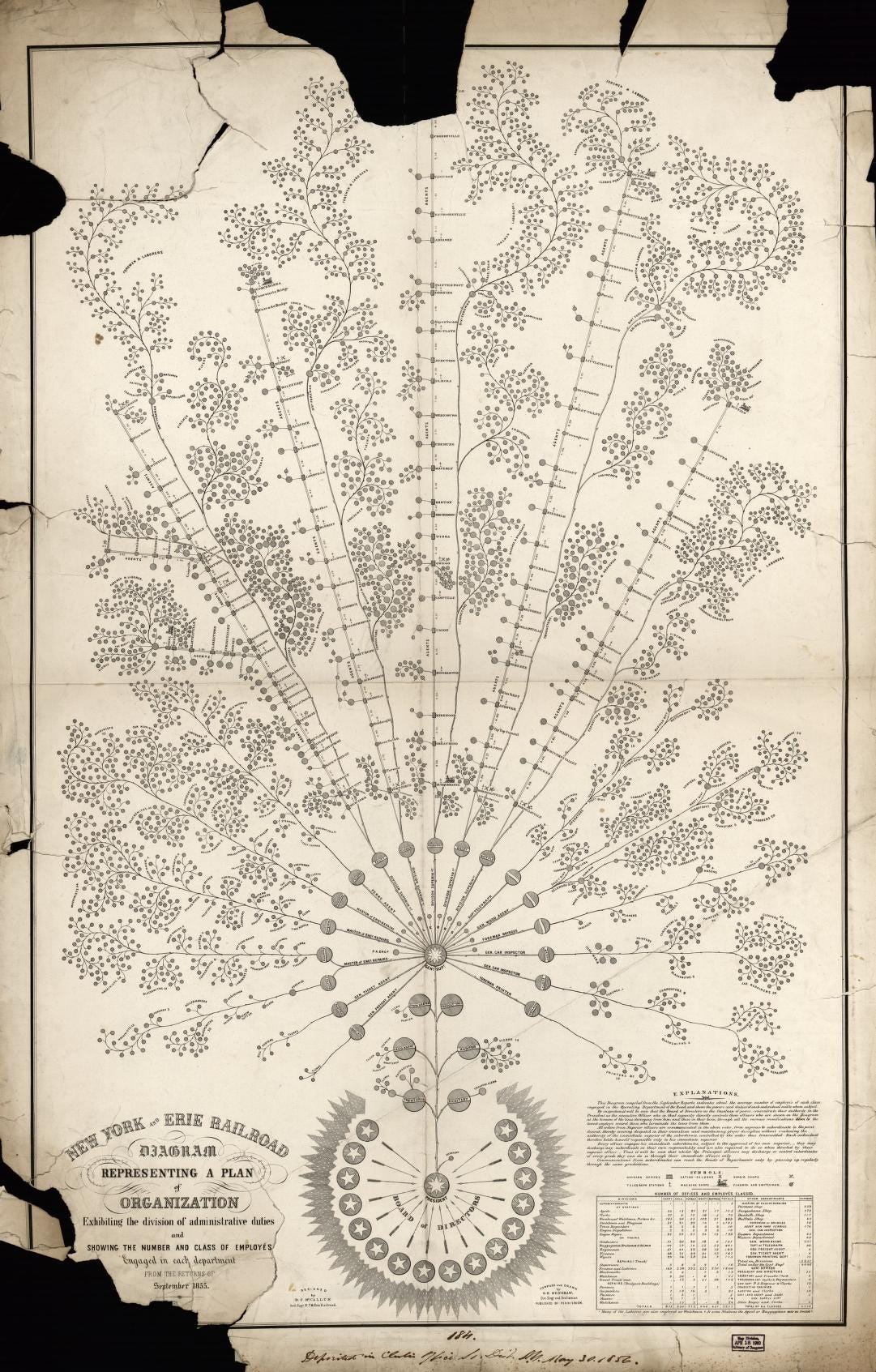

A clear sign of lower agency in corporations is the org chart, a hierarchy of boxes more suited to feudal life than the modern, autonomous, innovation corporation. One of the earliest org charts was designed for the New York and Erie Railway. It wasn’t easy to manage such a sprawling entity, and control is critical for safety and reliability on trains. The Railway’s chart was the opposite of the modern box hierarchy. We are used to putting everyone neatly below someone else, often with confusing dotted lines. The New York and Erie Railroad put the people in the highest authority at the bottom, in a circle, like the roots of a tree. Spread outwards from them like the trunk and branches were the individual railway lines. In this way, the autonomy of the person at the point of the track, signal, or carriage was preserved and made central to the way the business thought about itself. The chart was fluid and organic: it respected the individual and expected decisions to be made. No-one feels autonomous like that looking at the modern clutch of boxes, which merely reports who manages who.

The New York and Erie Railroad chart is a response to Hayek’s knowledge problem. Only the superintendent on the line or at the station actually has the “tacit knowledge of time and place” that is needed to make critical decisions. The chart recognised this and identified the right people to manage inefficiencies. The C-suite was there to support the operation, not direct it. We hear a lot of corporate rhetoric of that sort today, but modern org. charts reflect a top-down hierarchy with little room for the tacit local knowledge that actually runs a business. In the Railroad’s system, decisions were made locally and information flowed to the centre. Too often today, decisions are made centrally and information flows downwards. The cascade is the enemy of autonomy and perhaps innovation. Is it any surprise that businesses run with box charts produce innovations no more exciting than flavoured water or cereal with banana chunks in?

The economists Nicholas Bloom and John van Reenan have shown that technology makes a difference here. They predict that the local head of a multinational will lose autonomy as these technologies roll out while nurses and technicians will gain autonomy. Information technology that gives employees access to data increases autonomy. Communication technology increases centralisation. Unfortunately the technology that provides data and technology that increases surveillance or distraction are often the same.

Slack started being more frictionless than email, data at your fingertips, and it's sucking the enterprise spirit out of corporate life now, with people overwhelmed by the soothing ping. Empowering your employees is useful. Give your paralegals LexisNexis and you empower them. But add multiple communications layers, give them Teams, and you are making them a cog in an information machine. One where by definition you're the decision maker and they're disenfranchised.

We have to choose—do we want to make it cheaper for employees to produce something or just to talk to each other?

A very strong comparison perhaps is the information diet analogy from financial markets. There are investors who specialise in millisecond intervals, intra-day intervals, week/month intervals, couple-year intervals and decade-plus intervals as their ideal trading period. Warren Buffett famously says, repeating Ben Graham, that you shouldn’t listen to Mr. Market just because he can provide you with a price every day. You should see it as noise. Even if the long arc of history points you in a favourable direction you don’t need to take stage directions every minute. He has a favourite holding period of forever.

Renaissance Technologies, the behemoth hedge fund whose Millennium fund has had the best public market performance of any fund ever, has a favourite holding period of milliseconds. It finds roughly 50.1% of its trades are profitable, holds thousands of simultaneous positions, and tries not to interfere with the computer’s predictions. The information edge they need, and the frequency they need, is tick by tick granularity.

But while financial services—arguably the closest humanity has made a system to analyse complex information across multiple timescales and make decisions to maximise an outcome—has sub-specialised in choosing the information diet that’s best suited to individual actors, filling all possible niches of information diet, the rest of society and management have gone the other way.

Most companies want to use ever more information in ever more granular fashion without asking if they have any way of using this information to create anything but chaos. The org. chart of hierarchical boxes has given us a mental model that prioritises the flow of information, not its use. In our modern organisational life asking for more information has become easier than making a decision, monitoring has become easier than analysing, and asking questions easier than trying to get to an answer.

As the master Robert Heinlein said:

A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyse a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.

We should aspire to no less from those who work with us.

Subscriptions

Some of you have very kindly pledged that you would pay to read The Common Reader if I turn on subscriptions. And so I have. Generosity is not to be shunned. If you would like to support my writing, you are now able to.

But—there is no obligation to pay and everything that is free to read now will will still be free to read. This is a question of accepting donations, not soliciting them. Depending on how many people decide they want to pay, I will think about what I can add, such as a bookclub. And of course, I remain open to requests, suggestions, and questions from all of you. Many thanks to all of you for reading, sharing, and paying.

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying The Common Reader, let your interesting friends know what you think. Or leave a comment.

If you don’t subscribe to The Common Reader, but you enjoy reading whatever’s interesting, whenever it was written, sign up now.

Great piece which I will save and reread. I am one of those benighted academics that occasionaly struggles with submitting research papers. It is getting better: all in one pdfs are becoming the norm. What is really difficult are the sheer numbers of papers you are asked to review now, given the torrent of submissions.

On top of this are constant demands for information on x, y, or from all sorts of places.

Your piece conspicuously avoids mention of ChatGPT. I can imagine it being trained on academic and corporate intranets. Suddenly the bing of emails, slack etc. will give way to the chatbots providing answers and reporting layers will be disintermediated. How do you see this developing?

Thanks for this piece. So much of this resonates with my experience. A bit depressing though - much focus on the diagnostic. A follow-up piece on potential solutions please!!!