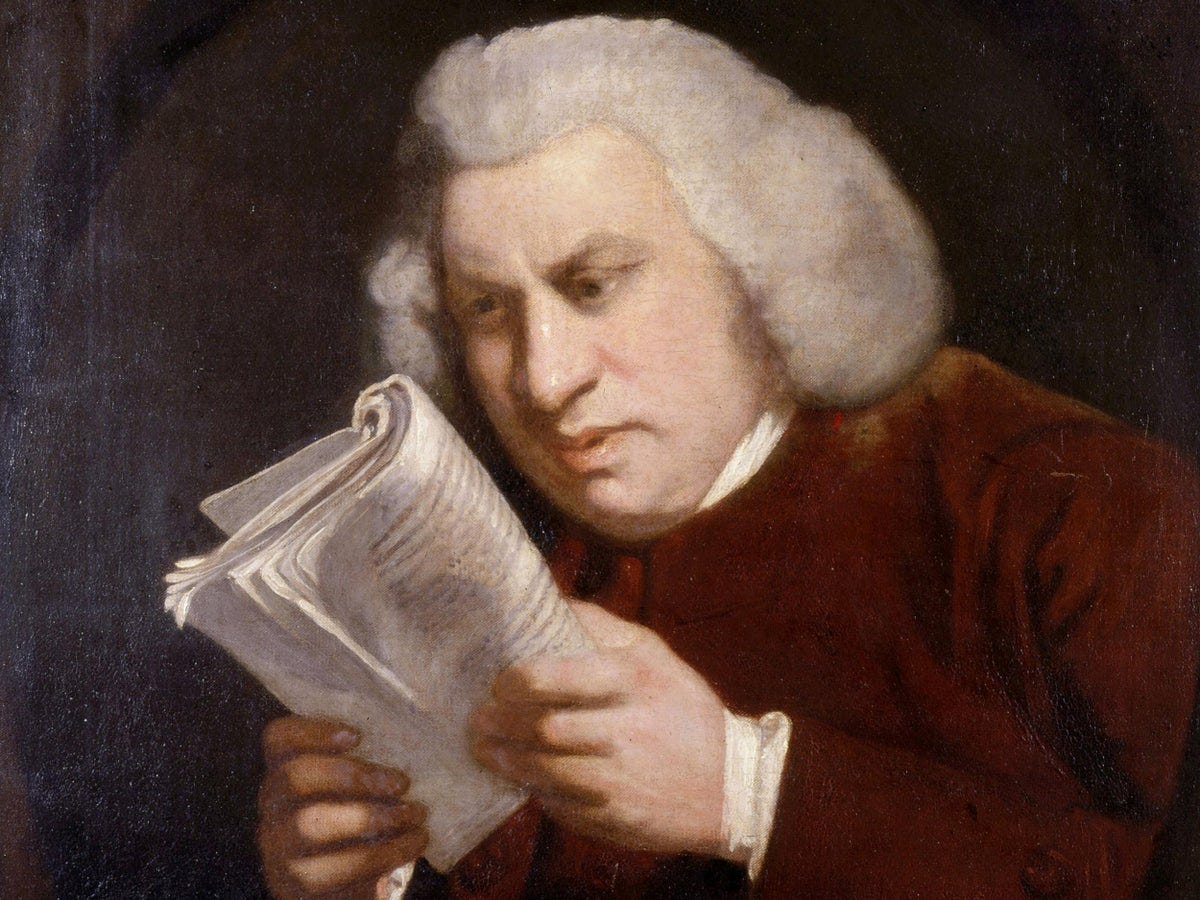

New Year's Resolutions with Samuel Johnson

Every long work is lengthened by a thousand causes.

Samuel Johnson was always terrified of his laziness. Usage of “terrified” has boomed in recent decades and the meaning has expanded — Johnson was not terrified in any exaggerated sense. He wasn’t terrified of idleness the way we might say we are famished when we have a late lunch, or in the way a football commentator might say a player is literally on fire. Johnson really was scared that he had wasted his God-given talents, and, because this was a sin, that he would suffer for it. Before he died, he was sometimes literally terrified of going to hell.

This might be why he accepted the commission from three publishers to write his Lives of the Poets when he was sixty-eight. He was already accomplished. He had produced the Rambler, the Dictionary, Rasselas, and his edition of Shakespeare. This hadn’t brought him quite the fame he had hoped for. Although he was famous enough to make the booksellers want his brand on their project, he seems to have underrated himself. He asked for two hundred guineas, got three hundred, but it was thought he could have got fifteen hundred. He always needed more money, but he had a government pension and enjoyed his leisure. His time was well spent reading, talking, going to supper clubs. Indeed, it was at a monthly dinner that he accepted the commission.

In 1772, five years before he accepted the job to write Lives of the Poets, he wrote a poem about a lexicographer (clearly himself) that included the lines:

He curs'd the industry, inertly strong,

In creeping toil that could persist so long.

So he vacillated between enjoying the release from hard work and feeling the unbearable lightness of being. He also knew he was incredibly talented. Paul Graham wrote about the interaction of talent and work when you are trying to achieve great things: “you need great natural ability and to have practised a lot and to be trying very hard.” Johnson knew he was talented (he says in the poem: “To you were giv’n the large expanded mind, The flame of genius, and the taste refin'd.”) and he had a massive accumulation of experience behind him. But retirement threatened a lack of hard work. One more push might get him closer to his desired reputation.

Graham says hard work often begins in early adolescence, as it did with Johnson. He was an astonishing Latin scholar by the time he went to Oxford. But knowing what you want to work on isn’t always enough. Hard work is a “complicated, dynamic system”; Johnson seems to have understood that. He knew, as Graham says, that hard work relies on you being honest with yourself. Johnson was exhausted from a life of toil, but also diminished from leisure. The impetus that made him write the Lives was psychological, moral, and practical

A mind like Scaliger's, superior still,

No grief could conquer, no misfortune chill.

Though for the maze of words his native skies

He seem’d to quit, ‘twas but again to rise;

Johnson’s 1772 poem is remarkably similar to Graham’s essay. Johnson was an infovore. He was interested in everything. Boswell reports his indefatigable interest in conversation about all subjects, including things like manufacturing processes. In this sense, he wasn’t a literary person, most concerned with writing, style, craft. He was a scholar, an information-hungry nerd.

The 1772 poem is a bit self-involved, but it is self-analytical. And not in that unbearable “let me tell you the story of my early life” way. He was trying to see himself objectively and in the effort wrote an essay about work and psychology. He knew the effects of weak wills on strong minds. And he knew the benefit of hard work.

The listless will succeeds, that worst disease,

The rack of indolence, the sluggish ease.

Johnson’s other worry, alongside his eternal life, was that he was going mad. The year he started Lives he resolved for “more efficacy of resolution” after his “barren waste of time” in the last year. In the poem, idleness leads to “phantoms of the brain” and “vain opinions.” Work would keep him sane.

The poem anticipates Graham: “Working hard means aiming toward the center to the extent you can. Some days you may not be able to; some days you'll only be able to work on the easier, peripheral stuff. But you should always be aiming as close to the center as you can without stalling.” And so Johnson wrote the Lives of the Poets.

He was also a firm believer that getting older didn’t mean getting less intelligent. He understood that some people are opsimaths. His retirement project would show the world that he was still the great Doctor. Writing Lives of the Poets was a way to demonstrate that his powers were not in decline. This was an explicit topic in the Life of Waller: we might read this passage as autobiography, as much as biography.

That natural jealousy which makes every man unwilling to allow much excellence in another, always produces a disposition to believe that the mind grows old with the body; and that he, whom we are now forced to confess superior, is hastening daily to a level with ourselves. By delighting to think this of the living, we learn to think it of the dead; and Fenton, with all his kindness for Waller, has the luck to mark the exact time when his genius passed the zenith, which he places at his fifty-fifth year. This is to allot the mind but a small portion. Intellectual decay is doubtless not uncommon; but it seems not to be universal. Newton was in his eighty-fifth year improving his chronology, a few days before his death; and Waller appears not, in my opinion, to have lost at eighty-two any part of his poetical power.

(Waller is also worth reading for the humour: “Waller was not one of those idolaters of praise who cultivate their minds at the expense of their fortunes.” And it contains one of Johnson’s most underrated lines: “Many qualities contribute to domestic happiness, upon which poetry has no colours to bestow… There are charms made only for distant admiration. No spectacle is nobler than a blaze.”)

Throughout the Lives, Johnson’s judgements are stinging. Gray is denigrated for almost all of his work, other than the Elegy, of which he says, “I rejoice to concur with the common reader”.1 (Milton doesn’t get off lightly, either.) The Lives are a lesson in how to give your opinion without being opinionated. But this is not an essay about the Lives as writing — we are interested in Johnson and his laziness, in how he overcame it; in how the Lives affected his life. The new year approaches, and we are in the season of resolutions. Johnson was, unsurprisingly for a neurotic moralist, a great writer of resolutions.

A typical diary entry from 1738 reads, “Oh Lord, enable me to redeem the time which I have spent in sloth.” So this was a lifelong preoccupation. His resolutions, which you can find in Prayers and Meditations, were not like ours. His resolutions were moral, and theological; they were about his character.2 For the new year in 1777, he wrote:

Grant, O Lord, that as my days are multiplied, my good resolutions may be strengthened, my power of resisting temptations increased, and my struggles with snares and obstructions invigorated… Grant me true repentance of my past life; and as I draw nearer and nearer to the grave, strengthen my faith, enliven my hope, extend my charity, and purify my desires.

For Easter in 1777, just about the time he accepted the commission for the Lives, he wrote:

I was for some time distressed, but at last obtained, I hope from the god of peace, more quiet than I have enjoyed for a long time. I had made no resolution, but as my heart grew lighter, my hopes revived, and my courage increased; and I wrote with my pencil in my common prayer book:

Via ordinanda

Biblia Leganda

Theologiae opera danda

Serviendum et laetandum

That is: to order my life, to read the bible, to study theology, to serve god with gladness.3 His resolutions were often so similar because a good resolution will help us make progress but never be complete. Wisdom is the work of a lifetime. And work, as we see here, was the mechanism that helped him to live up to his resolutions. It was his view that no really good literary life had been written. This was his chance to change that. It was a big project: big enough to be a contribution to his resolutions.

As we approach the new year we can take Johnson’s example — to resolve, again, to improve at what matters, and has mattered, and will matter, most to us; to hold ourselves to as high a standard as possible, so that we will improve through our partial failures; and to be ready, waiting, and asking, for opportunity, so that through our work we can find ways of testing, and proving, our resolution. To help maintain your resolve this year, keep this quote from the Life of Pope somewhere where you will be forced to read it every now and then.

The distance is commonly very great between actual performances and speculative possibility. It is natural to suppose, that as much as has been done to-day may be done to-morrow; but on the morrow some difficulty emerges, or some external impediment obstructs. Indolence, interruption, business, and pleasure, all take their turns of retardation; and every long work is lengthened by a thousand causes that can, and ten thousand that cannot, be recounted. Perhaps no extensive and multifarious performance was ever effected within the term originally fixed in the undertaker's mind. He that runs against Time, has an antagonist not subject to casualties.

Every long work is lengthened by a thousand causes — our lives, if they are well lived, are long works. Take Samuel Johnson’s advice. Resolve, work, fail, and resolve again.

Other Common Reader essays about Johnson

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying The Common Reader, let your interesting friends know what you think. Or leave a comment at the bottom.

If you don’t subscribe to The Common Reader, but you enjoy reading whatever’s interesting, whenever it was written, sign up now.

This is one of Johnson’s most enjoyable put-downs: “There has of late arisen a practice of giving to adjectives, derived from substantives, the termination of participles; such as the cultured plain, the daisied bank; but I was sorry to see, in the lines of a scholar like Gray, the honied Spring. The morality is natural, but too stale; the conclusion is pretty.”

Johnson did make specific, goal-based, resolutions, such as the ones below from April 6, 1777, but they were called his purpose and are more fundamental than the genre of resolutions like “get a new job” or “finish the house”.

My purpose once more is,

To rise at eight.

To keep a journal.

To read the whole Bible, in some language, before Easter.

To gather the arguments for Christianity.

To worship God more frequently in public.

On, or about, the day he accepted the commission, Johnson wrote:

“I ROSE, and again prayed, with reference to my departed wife. I neither read nor went to church, yet can scarcely tell how I have been hindered. I treated with booksellers on a bargain, but the time was not long.”