Robed as Destinies: Magna Carta, Thomas Jefferson, and bobblehead Nixon.

I saw the Declaration of Independence

We spent the morning at the National Gallery of Art, a treasure-house if ever there was one, and while we drank coffee in the sculpture garden, we realised the National Archives were over the road. The children were grouchy, but the prospect of seeing the Declaration of Independence made the little detour persuasive.

The government shutdown only ended two days ago, so there was no queue. There was, indeed, a great absence of people. We were through security in seconds. I chanced to overhear that a Magna Carta was on display, from 1297. I have not seen one since I was a boy, on a trip to Lincoln Castle, where they have the original 1215 document. I stood in happy awe, now as then.

How seriously the Americans take their history. Magna Carta was displayed at the start of an exhibition about slavery, democracy, and suffrage. They make a direct link between the Barons holding bad King John to account in the thirteenth century and the later marches for freedom in the New World. From a marshy field in medieval England to the twentieth-century streets of Selma.

Call that link a myth if you like, plenty have, or whittle it down to size with pedantic accounts of Magna Carta as a bill of barons’ rights, nothing more. But here is the beginning of the idea that changed the world. No king can breach the rule of written words.1 And America knows it, knows it in the blood, knows it in the imagination.

Upstairs in the rotunda, we saw just how seriously the Americans take their history. I am constantly told by regretful Yanks that their country doesn’t have real history like England. Pish! In the rotunda of the National Archives, behind the sort of huge metal gates once reserved for the holy ends of great cathedrals, we stood in line to see the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights.

To my children’s relief, the queues were short, so I only had time to recite one or two phrases. What rolling periods, what balanced syntax, what rousing swells of phrase! O, you can hear that the young Jefferson had been an obsessive reader, a man immersed in Milton, Shakespeare, Addison, Pope. This is how you make the world take note!

Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed.

Read it aloud. It stirs the blood, every time. Alas, while Jefferson’s words will live for as long as we are sensible enough to remember them, the writing on the document itself is faded. Cruel irony for such strong lines as “We hold these truths to be self-evident” and “let Facts be submitted to a candid world.” Still, the paper holds a mystical charm. We saw John Adams’s signature on the Bill of Rights, as clear as clear could could be. I felt, as I had done in the National Gallery, in the presence of something sublime.

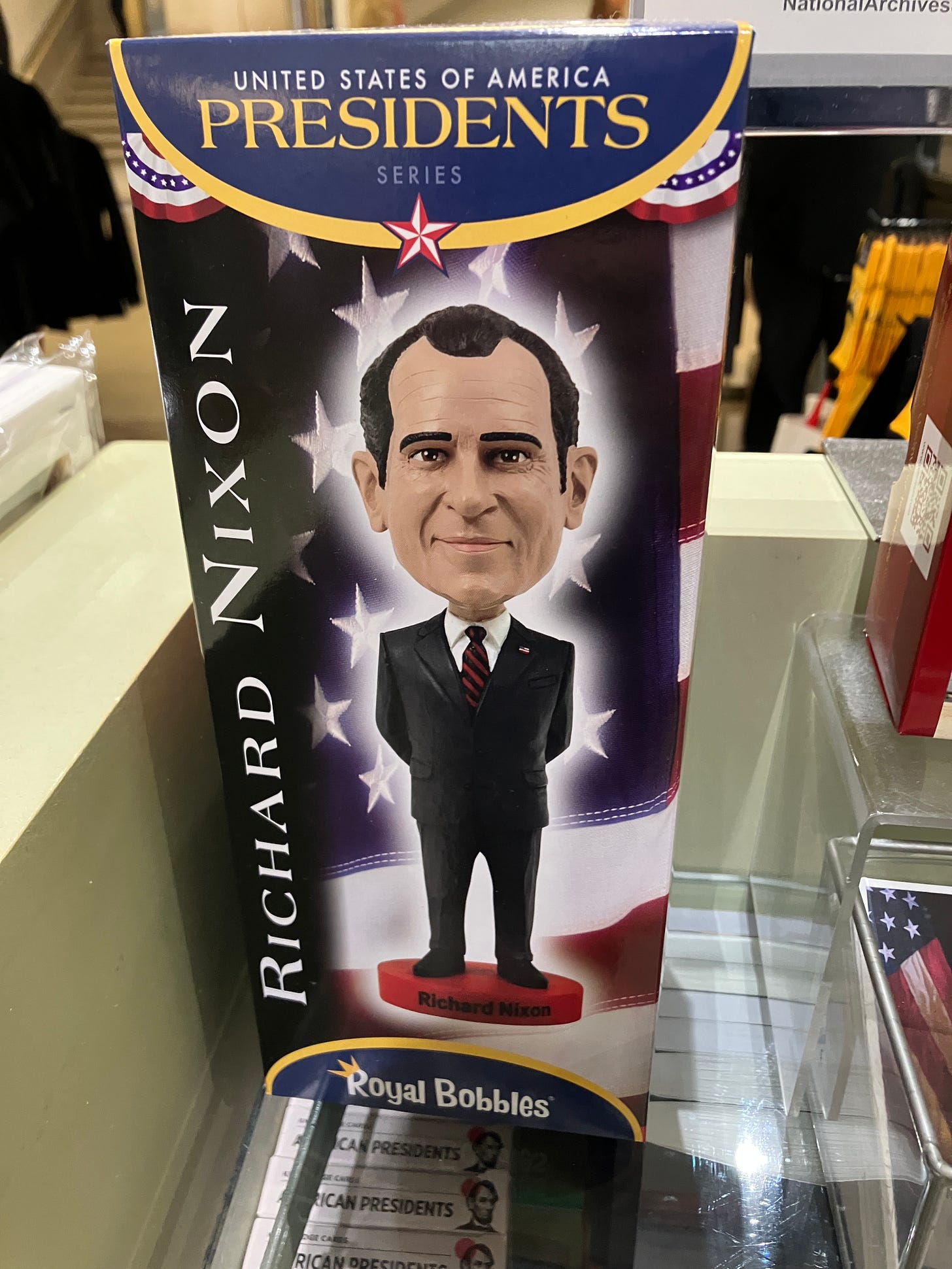

It exemplifies the American spirit that such dramatic respect is paid to these documents, in such semi-religious architecture, and that once you have paid reverence you visit the gift shop, where the Declaration of Independence is printed on a t-shirt and bobblehead dolls of President Nixon are for sale. One does not need to be high-brow to appreciate the miracles of political history.2

One little word in the Declaration captures that spirit more than any other. Candid. “Let Facts be submitted to a candid world.” Candid didn’t mean then what it means now. Johnson defined it as: “Free from malice; not desirous to find faults; fair; open; ingenuous.” Jefferson was asking for a fair hearing: he wanted to be received in the democratic (or, more properly, republican) spirit in which he pleaded.

“Ingenuous” is the most intriguing part of Johnson’s definition of candid. It’s a word we forgot along the way, only talking now of the disingenuous. Johnson tells me it means “Open; fair; candid; generous; noble.” but also “Freeborn; not of servile extraction.”

And that captures the evil dilemma at the heart of the founding, which is discussed in the room where I saw the Magna Carta.

By talking to a candid world, Jefferson was talking to a free world—he was not talking to the enslaved men, women, and children in his own country, on his own estate, in his own bloodline, who would never know the great freedom for which he called. He wrote in poetry, but his Declaration sought to govern in partial prose, to appropriate an old cliché. Jefferson had no intention to invoke this meaning: it is an echo of history, a dictionary coincidence that reminds us of a deeper truth.

The founding documents lie in their rotunda—robed as destinies, in Larkin’s phrase—more and more argued over, more and more disputed. Many of their mighty lines are more and more ignored. But Jefferson is American gospel, as Gore Vidal once said. His words still move the world, just as the Magna Carta still does. The idea lives.

It’s sometimes hard to see it this way, but dispute is what matters. Men more often require to be reminded than informed, said Johnson elsewhere. America is forever reminding itself of the great failures to live up to the dream that Jefferson set forth.

Those reminders still serve as the last best hope for freedom’s greatest country.

Or if he does, a Barons’ War ensues, as it did in England when John refused to obey Magna Carta.

In the restaurant of the National Gallery, I had seen the same principle in action. The man ahead of me was dressed very traditionally: tweed jacket, buff waistcoat, a wide-brimmed, blue-felt trilby hat. And just like the other gentleman wearing sneakers and baseball cap, he had the cheeseburger. In England, such attire often suggests a social profile averse to eating cheeseburgers in museums. In America, you stand in glory in front of Rothko and then head down for a Diet Coke, just as you pay homage to Jefferson before purchasing a souvenir bobblehead Nixon.

I'm glad you and your family are enjoying our great museums! Thanks for bringing the historical meaning of "candid" to my attention.

What a fascinating piece!! I can't imagine how surreal it was to look at those documents and what they stood for and then think about how things are going today.