Seamus Heaney: a jobber among shadows.

The development of his poetic idiom

Hushed and lulled

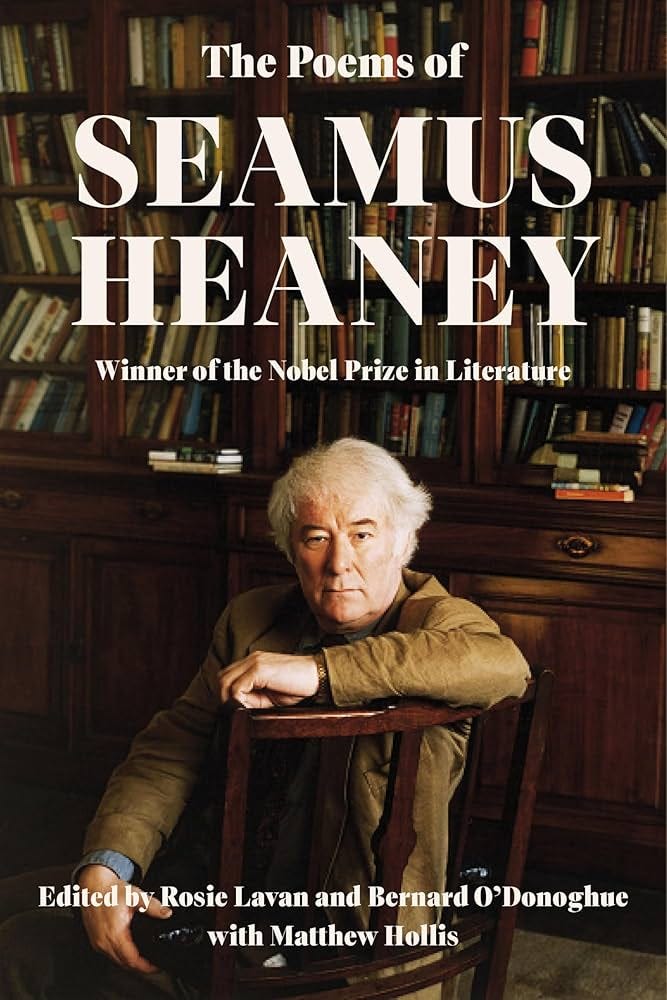

From the first word of the comprehensive new Poems of Seamus Heaney, Heaney writes in a familiar voice.

Hushed

And lulled

Lay the field, under a high-sky sun.

Hushed and lulled could have been the title of this volume. Heaney’s voice often is hushed and lulled, both his writing and his reading voice. There is much “hushed and lulled” imagery in Death of a Naturalist: “The squat pen rests, snug as a gun”, “Hunched over the railing”, “Snug on our bellies”, “Drifted through the dark of banks and hatches”. This hushed hunching is found in the earliest uncollected poems, but also in some of Heaney’s later work, such as Seeing Things: “Hunkerings, tensings, pressures of the thumb”, “that sniffed-at, bleated-into grassy space”, “Firelit, shuttered, slated, and stone-walled”, “claustrophobic, nest-up-in-the-roof/Effect”, “all hutch and hatch”.

This hutch-hatch snug-nested manner is the heart of Heaney’s forms as well as his tones. Like the poet who had the greatest-but-least-acknowledged influence on his work, Robert Frost, Heaney enjoys tightness—not the neat tightness of form in which Frost specialized, but the sort of tightness we associate with being hushed, slated, lulled, or stone-walled: his poems are packed, slotted, with meanings couching, crouching, bunching.1

In the seventh Glanmore Sonnet, from Field Work (1979), Heaney embodies the “flux” of the sea in repetitions of sounds and cells of rhythm. See how the vowels bob and swirl, and the lines are packed with compoundings, condensings.

Dogger, Rockall, Malin, Irish Sea:

Green, swift upsurges, North Atlantic flux

Conjured by that strong gale-warning voice,

Collapse into a sibilant penumbra.

Midnight and closedown. Sirens of the tundra,

Of eel-road, seal-road, keel-road, whale-road, raise

Their wind-compounded keen behind the baize

And drive the trawlers to the lee of Wicklow.

L’Etoile, Le Guillemot, La Belle Hélène

Nursed their bright names this morning in the bay

That toiled like mortar. It was marvellous

And actual, I said out loud, ‘A haven,’

The word deepening, clearing, like the sky

Elsewhere on Minches, Cromarty, The Faroes.

Half guessing, half expression

That poem leads us to the next of Heaney’s central qualities: “It was marvellous/ And actual.” In the early uncollected ‘Lines to Myself’, Heaney instructs: “You should attempt concrete pression/ Half guessing, half expression.”

This is notable: Heaney wants the persuasive pressure (“pression”) he puts on his concrete images to slip into something vaguer—half-guessing.

In this half-guessing pression, he follows Frost, who often leaves something implied for us to follow. “Glimmerings are what the soul’s composed of”, he wrote later—a Frostian line.

But while Frost’s meanings tantalize, they are discoverable, visibly submerged; Heaney is often more a poet of mood, sometimes somewhat inscrutable after all the compounding word-play. He repeats to himself, again in Seeing Things, “Be literal a moment”. But his literality is always in service to his aim, clearer and clearer as the years went by, to get close “to the music of what happens.”

Sometimes, for better and for worse, his verse seems to be all music. It would be too punning to say he was a poet of mood music, but there’s some truth snuggled in that phrase.

At his worst, Heaney is a pun artist. In 2011, reading at the 92nd Street Y, Heaney mistakenly said epitaph instead of epigraph (having begun by saying epilogue). This triple, unintentional word play, with its commingling of life, literature, and death, delivered with dry unintentional humour, is representative of the word-play that often characterises Heaney’s weaker work. His word-play is, playfully enough, not always a means of punning and double-meaning, but merely of playing with words, moving, swapping, and substituting them.

From ‘Aubade’, part of uncollected poems 1966-69.

From Cork to Malin the rummaging tide

Sluices, spends itself round the promontory,

Lighthouse, harbour and swallowing haven,

A bag of waters at whose centre I

Stay wide-eyed as an early wakened bride.

Heaney is reaching for idiomatic-poetic language, of the sort that characterizes his best work, which often sounds both poetic and like it was written by a local boy. But while “sluices” and “spends” achieve that, it can’t mean very much for a tide to rummage, and the image of the bay as a bag of waters is merely substitutive. It is an image without a purpose. If poetry makes language fresh it must do so with some intent or some end. The rest is dictionary fun.

But at his best, Heaney’s half-guessing pression creates huge emotional intensity. See the similarity of method in these two very different messages.

Roof it again. Batten down. Dig in.

Drink out of tin. Know the scullery cold,

A latch, a door bar, forked tongs and a grate.

And

O land of password, handgrip, wink and nod,

Of open minds as open as a trap,Where tongues lie coiled, as under flames lie wicks,

Where half of us, as in a wooden horse

Were cabin’d and confined like wily Greeks,

Besieged within the siege, whispering morse.

Early on, Heaney wrote: “Still, one does not lament, one just observes”, but the “hunched, bunched” method makes observation a lamentation. When he dug in to the poetry of North, this became clear. He aimed “to tell small truths instead of lies”.

Heavy with lightness: Heaney’s compound nouns

The noun compounds that animate the Glanmore Sonnet are a small but distinctive part of the voice of the early uncollected work: “blue-scooped sky”, “cloud-cream lick”, “jagged-edge noise”. In Naturalist we find a “flower-tender voice” and “time-turned words” (echoing the turned sod of his father’s farming) but mostly the compounds are more down-to-earth, like the “rat-grey fungus” of the blackberries. This matter-of-fact-compounding prevails until half-way into Door into the Dark (1969), in ‘Cana Revisited’.

No round-shouldered pitchers here, no stewards

To supervise consumption or supplies

And water locked behind the taps implies

No expectation of miraculous words.But in the bone-hooped womb, rising like yeast,

Virtue intact is waiting to be shown,

The consecration wondrous (being their own)

As when the water reddened at the feast.

Heaney has found something in that “bone-hooped womb” which he uses in the next poem, ‘Elegy for a Still-born Child’.

Your mother walks light as an empty creel

Unlearning the intimate nudge and pullYour trussed-up weight of seed-flesh and bone-curd

Had insisted on.

Unbearable, that “bone-curd”, with the almost paradoxical state of being that Heaney follows up, once the baby’s “collapsed sphere/Extinguished itself” and the mother is “heavy with the lightness in her.”

Heaney does little with this technique (“big-voiced ancestors”) in his uncollected poems after Door into the Dark, but in two poems from Wintering Out, Heaney finds a new breadth for the compound noun, and integrates it as part of the overall pression and compression of his aesthetic.

‘Anahorish’

My ‘place of clear water’,

the first hill in the world

where springs washed into

the shiny grassand darkened cobbles

in the bed of the lane.

Anahorish, soft gradient

of consonant, vowel-meadow,after-images of lamps

swung through the yards

on winter evenings.

With pails and barrowsthose mound-dwellers

go waist-deep in mist

to break the light ice

at wells and dunghills.

There is something essentially Heaneyish about “vowel-meadow, after-images”, as if his whole art was a vowel-meadow that created after-images, — as if what we were receiving from him were not poetic images, but his own after-images, the remnants of his memory, which he can only capture, or attempt to capture, in the hutch and hatch of his vowel-meadow mood-music.

The swinging lamp (which recurs, memorably in his poem about Diogenes, and in Seeing Things) becomes a metaphor of the brief, partial, snug illuminations of poetry. In the next poem in the collection, there is a perfect line to describe this sort of after-image art: a jobber among shadows.

‘Servant Boy’

He is wintering out

the back-end of a bad year,

swinging a hurricane-lamp

through some outhouse;a jobber among shadows.

Old work-whore, slave-

blood, who stepped fair-hills

under each bidder’s eyeand kept your patience

and your counsel, how

you draw me into

your trail. Your trailbroken from haggard to stable,

a straggle of fodder

stiffened on snow,

comes first-footingthe back doors of the little

barons: resentful

and impenitent,

carrying the warm eggs.

Here, as in the famous poem in Death of a Naturalist where Heaney stumbles around behind his father in the farm, the after-images of the poem’s vowel-meadow come from Heaney tracking, in his imagination, a figure from the past.

Lie down

in the word-hoard

The compound-pression-aesthetic came to a new brilliance in North (1975). In Naturalist “The sod rolled over without breaking” as Heaney’s father ploughed; now, as the Neolithic men preserved in ancient Irish bog are discovered, in ‘Belderg’:

The soft-piled centuries

Fell open like a glib:

They were the first plough-marks,

The stone-age fields

A glib was an old Irish hairstyle, in which the hair was worn in a long fringe that hung over the face, perhaps open at the eye. It was a thick, matted manner of hair, disdained by English colonists. Heaney’s soft-piled centuries thus sounds like both the bog and the hair, both distinctively Irish. History compounds with the present. At the end of the poem Heaney talks of Mossbawn, his childhood home

I’d told how its foundation

Was mutable as sound

And how I could derive

A forked root from that ground,

Make bawn an English fort,

A planter’s walled-in mound.Or else find sanctuary

And think of it as Irish,

Persistent if outworn.

‘But the Norse ring on your tree?’

I passed through the eye of the quern,Grist to an ancient mill,

And in my mind’s eye saw,

A world-tree of balanced stones,

Querns piled like vertebrae,

The marrow crushed to grounds.

The querns are stone discs used to grind wheat, and the eye Heaney passes through in his mind’s eye is the hole at the centre of the stone: the grist mill becomes a portal, mutable as sound, to take him to the world-tree of the past, the piled-up remains of history, which compounds into Irish identity now, beyond simple politics, persistent if outworn.

North has more compound noun phrases than previous collections: “river-veins”, “dough-white hands”, “dulse-brown shroud”, “ocean-deafened voices”, “thick-witted couplings”, “dark-bowered queen”. The poem ‘North’ gives something like an aesthetic statement of Heaney’s methods, when he hears the “ocean-deafened voices” from the past.

It said, ‘Lie down

in the word-hoard, burrow

the coil and gleam

of your furrowed brain.Compose in darkness.

Expect aurora borealis

in the long foray

but no cascade of light.Keep your eye clear

as the bleb of the icicle,

trust the feel of what nubbed treasure

your hands have known.

The bleb is an air bubble, caught in the ice, and thus entirely clear. Heaney is that sort of writer: accused of not being political enough, because he preserved himself as the bleb in the icicle of his time, in order that he could keep his eye clear by burrowing in the word-hoard.

This ancient history allows Heaney to move on from the compounding methods of Keats into the Saxon, the Irish, the distinctively Heaney. This is a turning point. These lines, like the poem at the start of the collection ‘Sunlight’, move us into a distinct voice and manner: the cool hard feel of the potatoes in Naturalist has become the nubbed treasure of North.

Like his father and grandfather he kept digging, going down and down for the good turf. ‘Strange Fruit’ shows this development in stark, tragic terms.

Here is the girl’s head like an exhumed gourd.

Oval-faced, prune-skinned, prune-stones for teeth.

They unswaddled the wet fern of her hair

And made an exhibition of its coil,

Let the air at her leathery beauty.

Pash of tallow, perishable treasure:

Her broken nose is dark as a turf clod,

Her eyeholes blank as pools in the old workings.

Diodorus Siculus confessed

His gradual ease with the likes of this:

Murdered, forgotten, nameless, terrible

Beheaded girl, outstaring axe

And beatification, outstaring

What had begun to feel like reverence.

In Naturalist, the flax-dam festered, “rotted there, weighed down by huge sods”. The flax “sweltered” and bubbled. But underneath was clotted frogspawn, terrifying life. It is the “slap and plop” of the frogs “cocked on sods” that make an obscene threat to the young Heaney. There is an early uncollected poem that tells the story of how the flax came to fester.

The flax was pulled by hand once it had ripened,

Bound into tall green pillars with rush bands

And buried underwater, roots upwards.

When the dam was full they loaded stones and sods

On top, then left the whole thing for three weeks

To rot, to stink…

Heaney describes how men “stood waist deep/ In the fouled water” to dig out the festered flax, so it could dry in the sun and be spun into fabric. Heaney was obsessed early with the “putrid” nature of this “slime and smut”.

Now, in ‘Strange Fruit’, Heaney has found a more tragic, ancient sort of putrid festering: “Murdered, forgotten, nameless, terrible.” This is a strong line, like something out of Donne. The opening “here” echoes the loving domesticity of ‘Sunlight’ at the start of the collection.

here is a space

again, the scone rising

to the tick of two clocks.And here is love

like a tinsmith’s scoop

sunk past its gleam

in the meal-bin.

Where is the “here” of ‘Strange Fruit’? The title is an obvious reference to a Billie Holiday song about a lynching, which is a setting of a poem by Abel Meeropol.2 Heaney’s image of the gourd echoes Meeropol’s “the bulging eyes” of the hanged victims. Meeropol’s “fruit for the crows to pluck” becomes Heaney’s tragic “perishable treasure”, a deliberate echo of the “nubbed treasure” from ‘North’. So the here could be the Neolithic times, the Ireland of Heaney’s times, the USA of the civil rights era and the Jim Crow South.

What Heaney finds hushed and lulled in the turf of history is just as disturbing as what he is not writing about directly when he is hatched and hutched in the bleb of his icicle, away from the partisan calls to write poetry for one side or another, rather than a poetry of humanity. In the second part of North, Heaney defended his burrow in the word-hoard.

The times are out of joint

But I incline as much to rosary beadsAs to the jottings and analyses

of politicians and newspapermen

Who’ve scribbled down the long campaign from gas

And protest to gelignite and sten,Who proved upon their pulses ‘escalate’,

‘Backlash’ and ‘crackdown’, ‘the provisional wing’,

‘Polarization’ and ‘long-standing hate’.

Yet I live here, I live here too, I sing,

Can poetry be an answer to humanity’s perpetual violence? (Helen Vendler said that in North Heaney proposed that rather than Catholic and Protestant, loyalist and nationalist, what was happening was “a generalized cultural approval of violence, dating back many centuries.”) “Now as news comes in/ of each neighbourly murder/ we pine for ceremony,/ customary rhythms.” Can Heaney’s customary rhythms “draw the line through bigotry and sham”?

At the end of ‘Whatever You Say Say Nothing’, Heaney is more pessimistic: “We hug our little destinies again.” This is a low point for Heaney’s pessimism expressed in the hutch and hatch of his compressed style, “unhappy and at home.”

Opened ground

In Field Work (1979), these themes recur and Heaney gives some freedom to method in ‘After a Killing’.

There they were, as if our memory hatched them,

As if the unquiet founders walked again:

Two young men with rifles on the hill,

Profane and bracing as their instruments.Who’s sorry for our trouble?

Who dreamt that we might dwell among ourselves

In rain and scoured light and wind-dried stones?

Basalt, blood, water, headstones, leeches.

The new range Heaney has discovered becomes declamatory, too, in memorable lines:

The way we are living,

timorous or bold,

will have been our life.

It is in the Glanmore Sonnets that this new life, the opened ground of Heaney’s development, is most revealed. Now new sods roll over without breaking: Heaney was digging deeper still: “Vowels ploughed into other: opened ground.”

The music of Seeing Things is starting to be heard.

Sensings, mountings from the hiding places,

Words entering almost the sense of touch

Ferreting themselves out of their dark hutch—

‘These things are not secrets but mysteries,’

Oisin Kelly told me years ago

In Belfast, hankering after stone

That connived with the chisel, as if the grain

Remembered what the mallet tapped to know.

Then I landed in the hedge-school of Glanmore

And from the backs of ditches hoped to raise

A voice caught back off slug-horn and slow chanter

That might continue, hold, dispel, appease:

Vowels ploughed into other, opened ground,

Each verse returning like the plough turned round.

So much of what Heaney has been attempting and experimenting so far is here, and done with so much grace and density. He once said, of politics, “The desire was to get through the thicket, not to represent it”, but that is only possible with the thicket of language, what is here called “the hedge-school of Glanmore”, that comprises his essential style.

The constant looking back—to his father, to Ireland’s history, to the Vikings, the Norse—is part of the constant revising of his own poetry: the use and reuse of words and phrases, which makes poetry like digging, “Each verse returning like the plough turned round.” Oisin Kelly was a sculptor, and the idea that “the grain/ Remembered what the mallet tapped to know” is a development of the early poem ‘Personal Helicon’, about Heaney as a child calling down into wells: “Others had echoes, gave back your own call/ With a clean new music in it.”

Here, finally, is the music of what happens, the hutch and hedge-school and thicket of language that helps Heaney capture the world, see it in his bleb—show it to us in a clean new music that will now define Heaney.

The high-point of Field Work is a poem called ‘Song’, justly famous among Heaney’s work, which uses many of the words and images he returns to—wet, alder, bird, music—and in one short perfect poem expresses so much about his whole aesthetic.

A rowan like a lipsticked girl.

Between the by-road and the main road

Alder trees at a wet and dripping distance

Stand off among the rushes.

There are the mud-flowers of dialect

And the immortelles of perfect pitch

And that moment when the bird sings very close

To the music of what happens.

Now the closeness of Heaney’s method, which makes him so elegiacally empathetic to people as people, beyond politics and violence, is expressed as a union of art and nature. In one of the Glanmore Sonnets, he writes: “I fell back to my tree-house and would crouch/ Where small buds shoot and flourish in the hush.” Dialect, perfect pitch, and the music of what happens all meet in such lines.

There is an echo of Keats in the phrase “where small buds shoot”. In La Belle Dame sans Merci, Keats wrote: “The sedge has withered from the lake/ And no birds sing.” Heaney wrote in an early uncollected poem: “no tree rustles/ No sedge whispers”. Heaney has also relied on the density of Hopkins. The influence of a poem like Hopkins’s ‘Spring’ will be immediately apparent.

Nothing is so beautiful as Spring –

When weeds, in wheels, shoot long and lovely and lush;

Thrush’s eggs look little low heavens, and thrush

Through the echoing timber does so rinse and wring

The ear, it strikes like lightnings to hear him sing;

The glassy peartree leaves and blooms, they brush

The descending blue; that blue is all in a rush

With richness; the racing lambs too have fair their fling.

It strikes like lightnings to hear him sing. That is the effect Heaney is constantly reaching for, the strike like lightning that feels like song. In the uncollected ‘Villanelle for Marie’, the first speaker defines love as “the song maintained by singing.” And we can see his poetry as an attempt to maintain the song of a lightning strike, to preserve some of the music of what happens, to discover what he called (writing of Thomas Hardy playing dead in a field of sheep), “the perfect pitch/ Of his dumb being.”

Frost’s presence is apparent on the first page. “The mower was whetting his scythe…” Heaney writes,

Close hills

Shimmered

Liquidly, fascinating the mower,

Lark’s trills

Shimmered

Down the thin burnt air. Lower

And deeper and cooler sinks now

The sycamore’s shade, and naked sheaves

Are whitening on the empty stubble.

This is the poem that begins

Hushed

And lulled

Lay the field

reminding us of Frost’s “my long scythe whispering to the ground”. Heaney’s succession of images—hills, lark, air, shade, sheaves, stubble—echoes Frost: “the earnest love that laid the swale in rows,” coming after “something about the heat of the sun,/ Something, perhaps, about the lack of sound” before he “leaves the hay to make”. When Heaney then instructs himself, a few poems later, to aim for “concrete pression”, we think of ‘The Death of the Hired Man’, ‘Blueberries’, or ‘Out, Out—’, which so strongly influenced Heaney.

Southern trees bear a strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black body swinging in the Southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.Pastoral scene of the gallant South,

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth,

Scent of magnolia sweet and fresh,

And the sudden smell of burning flesh!Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck,

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck,

For the sun to rot, for a tree to drop,

Here is a strange and bitter crop.

I liked this very much indeed. It gave me great pleasure to think again about Heaney (who I wrote on to get my place at Oxford).

I don’t agree entirely over punning. I don’t see it as a dictionary dance. I feel this criticism is the same as that made of Dylan Thomas for aligned verbiage ( and indeed I got it in the neck later when I studied creative writing in Oxford). It’s a habit steeped in the same space as Anglo-Saxon keening. It is finding pattern. Keening finds pattern in the whale road because it implies sea and in its phonetics slaughter. Heaney finds pattern in phonetics which says if it sounds like that it is aligned - we don’t need to know, like a Rothko why in a conscious sense; a guttural sense it’s of a tribe. It’s the authentic, the concrete.

Meaning must be in the sound of the word. That is the only certainty. And so it isn’t a pun. Just as four and death are not puns in mandarin. We don’t know why but there is a reason they sound similiar and it counts.

It is making language physical in sound Tree and branch go together in a wood . Sounds go together in the forest of language and profoundly. What he is saying is that they do so more than meaning. Signifier and signified are arbitrary. Onomatopoeia is not. And so if sounds club together, it matters.

Hope that makes sense. I loved your analysis very much. Heard him speak as a professor in Oxford. What a poet and thinker.

One of my favorite pieces of yours, Henry! I’m so glad you didn’t rush through it. I fell in love with Heaney’s translation of Beowulf and since then have been allowing myself to ever so slowly collect his works, to savor them.