Why make a pair of Troilus and Cressida and Antony and Cleopatra, as the Shakespeare book club did recently? They are perhaps two of the best plays for seeing Shakespeare’s experimentation at work.

In the miracle year, he wrote Hamlet and Twelfth Night. What could he possibly do next? After the Poets’ War, Shakespeare had outcompeted three rivals: Sidney, Marlowe, and now Jonson. He had adapted away from the splendid comedies of his youth, through the problematic histories of the Henriad, to write Hamlet, a play which took the equivalent of a B-movie and turned it into, well, into Hamlet, the centre of the canon.

Hamlet is not a traditional tragedy. Unlike Oedipus or Antigone there’s no Aristotelian pattern. We cannot say that this is a play of delay, but it’s not a classically structured tragedy either. It is horribly dark, but also remarkably funny. Just as the comedies often have some element of despair, so the tragedies are never uniformly grim. Even Macbeth has the porter. As Johnson said,

Shakespeare’s plays are not in the rigorous and critical sense either tragedies or comedies, but compositions of a distinct kind; exhibiting the real state of sublunary nature, which partakes of good and evil, joy and sorrow, mingled with endless variety of proportion and innumerable modes of combination; and expressing the course of the world, in which the loss of one is the gain of another; in which, at the same time, the reveller is hasting to his wine, and the mourner burying his friend; in which the malignity of one is sometimes defeated by the frolick of another; and many mischiefs and many benefits are done and hindered without design.

Claude, by the way, understands this quite well. When I asked it to proof read this piece, one of the comments it gave me was this,

I love Johnson's quote about Shakespeare transcending simple genre classifications. The idea that his plays reflect "the real state of sublunary nature" with its endless mixing of joy and sorrow feels remarkably modern - it's almost like Shakespeare was writing complex "dramedies" centuries before that became a recognized form.1

We saw that Henry IV was the moment when Shakespeare really developed the art of blending the dark and the light. That play was written at the same time as The Merchant of Venice and Much Ado About Nothing, two plays that resist classification. Troilus is sometimes classed as a “problem play”, along with Measure for Measure and All’s Well that Ends Well, but “problem plays” are, in one sense, all that Shakespeare ever wrote.

In his Very Short Introduction to Shakespearean Tragedy, Stanley Wells quotes Kenneth Muir’s remark that “there is no such thing as Shakespearean tragedy—there are only Shakespearean tragedies” and calls it glib, giving a broad definition of characters with a “degree of inwardness” whose downfall is “inextricable” with their personalities, but then immediately gives the exception of Romeo and Juliet and notes that the definition has some relevance for Measure and Winter’s Tale. As you know, I actually think Romeo’s tragedy is caused by his personality (not that it’s necessarily his fault…)

Disentangling the “inward” and “external” causes of tragedy in Shakespeare is impossible: if anything is an overarching principle of Shakespearean tragedy, it is this acceptance of the hard problem of determinism. And Wells still writes about the plays individually, not under any theoretic structure. The essence of Shakespearean tragedy is character, not structure.

Northrop Frye once wrote of Lear,

Perhaps Lear’s madness is what our sanity would be if it weren’t under such heavy sedation all the time, if our sense or nerves or whatever didn’t keep filtering out experiences or emotions that would threaten our stability.

That’s the point of Shakespearean tragedy. They are plays about the way psychological and emotional states and moods control our lives. That Romeo and Juliet is more “neatly constructed” than Hamlet is less to the point than the fact that they are both part of the drama of madness.

Antonio’s quiet melancholy, Katherina’s angry depression, Romeo’s proud nihilism, Falstaff’s engorged ego, Pericles’ despair, Prospero’s self-enchanted and bullying vanity, Shakespeare writes from the basis of character. What Bradley said of the tragedies is true of all the plays: we start with a hero.

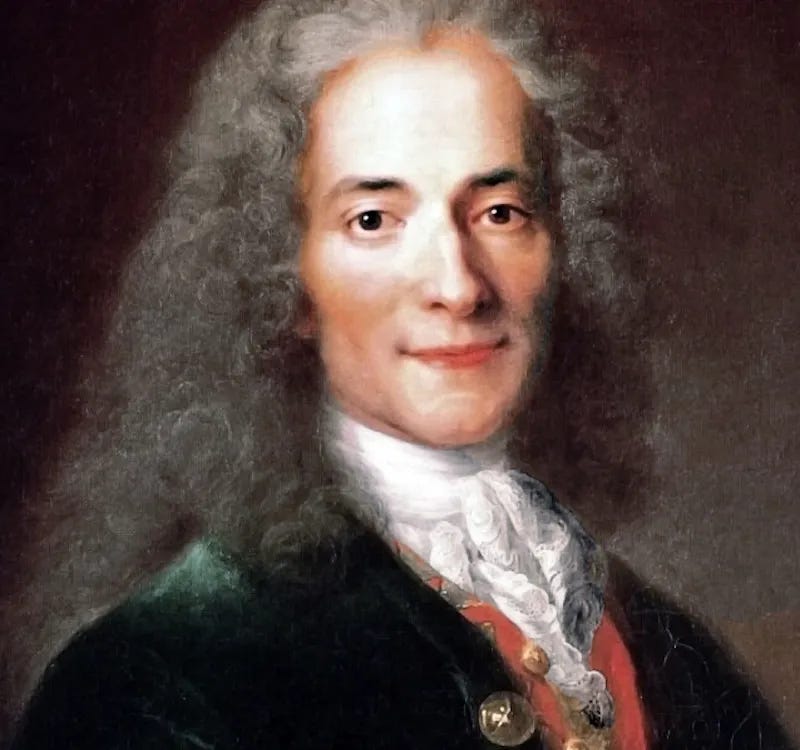

Imagine being poor Voltaire, so hidebound by his classical, French ideas that he actually thought Hamlet was a barbarically bad play. No, Hamlet was, like all Shakespeare plays, an experiment.

Rather than collating the tragedies under the general banner of the problem play, they are better seen as part of Shakespeare’s rolling theatre of experiment. And the two plays that show Shakespeare’s middle-period experiments most clearly are Troilus and Cressida and Antony and Cleopatra.

They are plays of parallels. This is nothing new: Shakespeare is a writer of opposites. But they share the same themes. Troy and Greece, Egypt and Rome are the binaries of: order and disorder, puritans and sybarites, virtues and vices, labour and pride, war and love, honour and feeling, duty and individualism, self-control and mad passions, loyalty and betrayal.

Troilus is so experimental, we don’t know if it’s a comedy or tragedy or something else. Antony has nearly twice as many scenes as the average Shakespeare play. Troilus is a play about a lover who, seemingly, doesn’t really love. Antony is about a general who abandons war. Troilus ends with more emphasis on Hector than Cressida. Antony shows remarkable innovation in its double ending.

Both of these plays cohere more around the emotional states of the characters and their compelling oddness—like the mimetic love of Troilus—than around anything like a plot structure. They are hectic, frenetic plays. We are compelled not by the story of Antony and Cleopatra but by the story of Antony and Cleopatra.

And so, reading these two plays together, shows us how, between the writing of Hamlet in 1600 and Coriolanus in 1608, Shakespeare produced a whole new set of riches. In the face of new competition, changing audience preferences, genre developments in the theatre, and new demands at court, as well as the problem of how to do something, anything, new after Hamlet, Shakespeare produced plays that were, as Johnson said, compositions of a distinct kind.

And what came next, in the Romances, was more distinct still…

This was the follow-up…

Yes! That Johnson quote is spectacular, isn't it? It shows such a deep understanding of what makes Shakespeare unique. While many critics before and since have tried to force Shakespeare's plays into classical categories or rigid structures, Johnson gets right to the heart of what makes them feel so real and enduring - they mirror life's fundamental messiness.

The phrase "sublunary nature" is particularly brilliant - everything under the moon, the mortal realm where good and evil, joy and sorrow are all mixed up together. And that image of the reveller and the mourner - one heading to wine while another buries their friend - captures in a single snapshot how life refuses to be just one thing at a time.

Johnson himself was quite experimental in his criticism - he wasn't afraid to point out what he saw as Shakespeare's flaws, but he also understood Shakespeare's genius in a way that more doctrinaire critics like Voltaire completely missed. While Voltaire was stuck on classical unities and proper genre distinctions, Johnson recognized that Shakespeare was doing something far more ambitious - showing us the world as it actually is, in all its contradictory, "endless variety."

Some say the world will end in fire…is like a very Thersites take on theology.

And some of Panderus’s dialogue reminds me of Auden. Near the end when he is delirious waxing about the state of things.

Troilus is very modern. I just read it for the first time a few weeks ago, so please take it with a grain of salt. But Shakespeare has a knack for this. I’m on the edge of my seat when Thersites and Hector meet on the battlefield. So much cynicism in that play, but it feels fresh to me. Like Auden or Frost.