Stop ignoring Harriet Taylor. She's the reason liberalism exists.

Together John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor were the poetry and logic of liberal philosophy. It's time to tell their story properly.

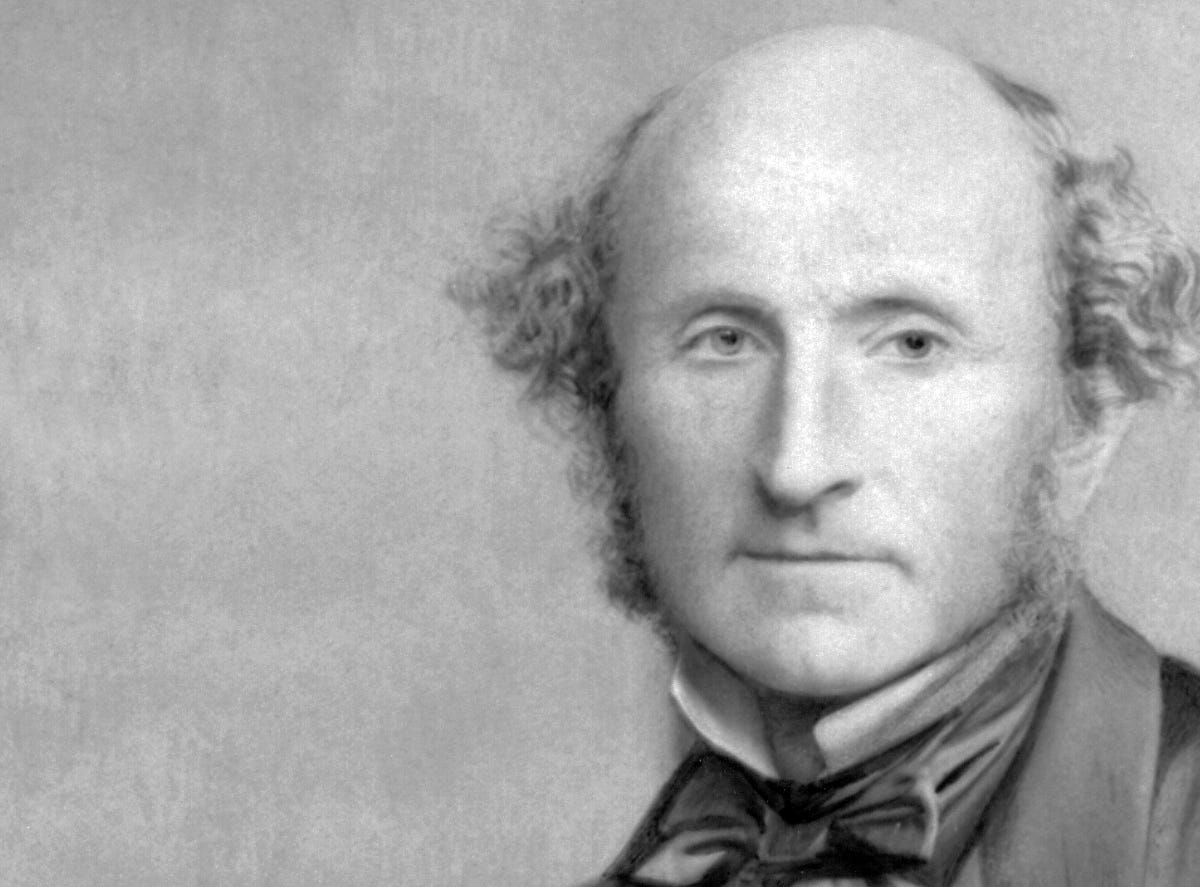

When John Stuart Mill sat down at the dinner where he met Harriet Taylor, he was a young man recently recovered from severe depression, renowned among friends for his genius, who hoped to produce influential economic and philosophical writings which would transform society. Harriet was a young mother, bored in her marriage and looking for intellectual stimulation, who held radical ideas of her own. They were well-matched dinner companions. No-one could have known what would follow. The friendship they began that night changed the world, and continues to do so today.

Within three years of that dinner, Harriet was separated from her husband, spending her time with John, and writing articles with him. Thus began an intense, platonic, twenty-year affair. Everything about their emotional life was tied up with their ideas. Radicals to their core, they wanted sexual equality, women’s votes, marriage reform, universal education, free speech, and liberty for all to conduct “experiments in living.” Their joint work raised many eyebrows. Their friendship got them shunned, mocked and denigrated. Slowly, they removed themselves from society, to avoid the crushing pressure of Victorian conformity.

They met in 1830. In 1851, when Harriet’s husband had been dead for two years, they married. There followed a series of writings—The Enfranchisement of Women, On Liberty, Mill’s Autobiography, and, most importantly, The Subjection of Women—that became the rallying cry of liberalism. The Mills were nineteenth century radicals who today look like prophets of common sense. Few writers have achieved more.

No-one before or since has made the case for freedom with such passion and precision, such relentless logic and such deep emotion. That’s why thousands of women all over the world took The Subjection as their bible in the fifty-year fight for women’s suffrage. (Some of them kept it under their pillow.) It’s why On Liberty is still quoted today by the young and the old, in every debate on free speech from the Oxford Union to the corners of Twitter. And it’s why On Liberty is still listed as one of the first works studied by new philosophy undergraduates.

So essential are these works to the way we live now that Mill is claimed as an inspiration on both sides of the political divide. The recent anniversary of his death drew a series of conflicting articles. There was an admiring profile of his balance and relevance in UnHerd and an assessment that he would be “fighting wokery” in the Telegraph. Academics write about what makes Mill relevant today, why he ought to be reclaimed for the left, and why he is the leading light for misguided conservatives. When Joe Rogan invited Dr. Peter Hotez to debate RFK Jr, National Review invoked Mill’s On Liberty. Andrew Tate has been called “J.S. Mill’s monster”. Mill has been cited in discussions about human rights in Iraq. On Liberty was carried by protestors there in 2019. He is cited globally in free speech debates. People quote him on Twitter every day. Robert McCrum listed On Liberty among the hundred best non-fiction books. David Brooks profiled Mill as a hero of democracy in the New York Times.

Mill is important on both sides of modern politics because his work is rooted in a very modern idea—that we should use our freedom to discover ourselves, develop our characters, become the best people we can become. Underneath his ideas about the public sphere was the intense belief that social reform starts with the individual. As we would say, we must be the change we want to see.

John said Harriet was his equal, an essential intellectual partner. All of his works, he said, were deep collaborations with her. But when people write about John, Harriet rarely makes the headline, sometimes not even the article.

Mill once wrote that logic and poetry together make the true philosophy. That’s what gives his and Harriet’s work its enormous, enduring power. They argued with great rationalism, but their words strike with the force of poetry. That marriage of poetry and logic comes directly out of their life together. Their relationship is inseparable from their work.

Despite this, Harriet is rarely given her share of the credit. That’s why it’s time for a new biography of John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor and their marriage of true minds.

All of this matters because the works we think of as John Stuart Mill’s are so essentially biographical it’s hard to see them as anything other than the joint production of John and Harriet’s life.

When the Mills got married, they sent blisteringly unkind letters to their relatives. Their families could not accept the marriage. And so, the Mills could not accept them. Writing to his sister, John said there was no such thing as insulting Harriet without insulting him. “My wife and I are one,” he wrote. And after twenty years of gossip, laughter, admonishment, and contemptuous disapproval—of being cut and shunned—the Mills were done. If the world cannot accept us, they seemed to say, we cannot accept the world.

Those letters, which must have cut their families deeply, were an act of devotion. Everyone else wanted them to remain apart for the sake of convention, for the sake of good manners. Be damned, said the Mills, in some of the most romantic writings of the nineteenth century, a mid-Victorian Romeo and Juliet for middle-aged radically-minded philosophers.

John and Harriet had spent years talking, writing, and thinking together. Now their ideas were being forged in the heat of experience. All the force and defiance of those letters comes back in On Liberty, six years later. What is so raw and tremulous in their letters—full of crossings out and emotional overstatement—becomes in On Liberty a procession of fierce arguments. All the anguish is recast in their trademark remorseless style, so intense one reader compared it to being looked at by a Basilisk.

Out of the fire of their lives they forged the gold of their work.

In 1865, John Stuart Mill became an MP. The most significant thing he did was to propose an amendment to the Second Great Reform Act. Had it passed, this amendment would have given women the same voting rights as men. Mill obviously lost, but he got more support than anyone expected, and the women’s suffrage movement began its sixty year journey to success.

Taking advantage of his success, Mill published The Subjection of Women in 1869, a much more radical call, not just for women’s votes, but the equality of the sexes. The Subjection was the global bible of the suffrage movement, from the USA to New Zealand. As Richard J. Evans said, it had “an incalculable influence on feminism almost everywhere.” One of the first students at Girton college called Mill her saint and hero because of that book.

After that, bills in Parliament in 1870, 1871, and 1872 gained up to 184 votes (330 were needed to pass a bill, so this was huge progress for such a radical issue) buoyed by Mill’s enormous influence. Had Mill lived, his biographer Michael St. John Packe said, it might not have taken sixty years of anguish and violence to give women the vote.

Harriet’s essay The Enfranchisement of Women sits at the core of John’s feminism. Written eighteen years before the Subjection, Harriet’s essay contains the seeds of the later work. One of Mill’s most fundamental ideas—that patriarchal marriage is similar to the legal status of the master-slave relationship—was amplified by Harriet. While she was writing the Enfranchisement, John wrote to Harriet about a Conference of Women held in Massachusetts. “Its tone is almost like ourselves speaking — outspoken like America, not frightened and servile like England.” Like ourselves speaking.

From specific ideas to the depth of feeling and the strength of tone, it is impossible to separate John and Harriet’s work on feminism. She and her work are a major reason why so many women called the Subjection their prized possession. It is thanks to her, as much as Mill, that we have modern liberalism.

John and Harriet did try to tell their story, but it was hijacked by a group of grumpy, Victorian patriarchs. Most of them didn’t know Harriet well enough to comment. But their misogynistic speculations dominated the story for decades. In some ways, they still do. It was only in 1951, when the economist Friedrich Hayek published a book of Harriet and John’s letters, that the true picture started to emerge. If they had told the whole truth to begin with, things might have been different.

The problem started with the Autobiography, published the year after Mill died. Mill wrote that what he owed Harriet intellectually, “though it is the smallest part of what you are to me, is the most important to commemorate.” That’s true, but by assuming people were “willing to suppose all the rest” the Mills left space for gross speculation.

This was a mistake. No philosopher’s sex life can have been more speculated upon. And what John owed Harriet intellectually has been remarkably contentious. Telling half the story left them open to generations of criticism and misunderstanding.

Within days of Mill’s death, old frenemies were writing articles denigrating Harriet, who was said to have “bewitched” John. Thomas Carlyle, who had started as an admirer, turned on Harriet when she was revealed not to be his disciple, calling her a “charmer” who snared Mill with “a dangerous passion”. The best Mill’s first biographer could do was to say Mill was “charmed” by Harriet. Again and again, the male explanation for Harriet was simple: blind infatuation. How scared they sound of the magical potential for a pretty woman to bewitch a rational man.

Mill thought Harriet was a genius, but this has been pooh-poohed by a succession of biographers, following in Carlyle’s footsteps. We think of a genius as someone who makes original discoveries. Not so, said Mill. Everything is original to someone, even the oldest knowledge. The true genius is someone who doesn’t accept what they are told but instead has “an intellect fitted to seek truth for itself.”

That’s exactly what Harriet had. Mill lived in a state of enquiry and development, investing in three areas of life: morality (what is right), prudence (what is expedient), and aesthetic (what is noble or beautiful). Harriet was his equal in all of this.

The lack of a smoking gun, showing that Harriet drafted this page or contributed that paragraph, has distracted biographers from what can be felt overwhelmingly in all the work Mill produced after they were married. Mill’s work is fundamentally different after Harriet. As he said in the Autobiography, before Harriet his feminism was “little more than an abstract principle.” After her, it became a crusade.

It is only with Harriet that Mill produced the white heat of On Liberty and The Subjection. A generation of Oxford undergraduates cherished his earlier book A System of Logic, but two generations of global women made the Subjection their guiding star. With Harriet, Mill harnessed a new energy and wrote books that changed the world.

In many ways, Mill’s most important contribution was the way in which he and Harriet lived. They were, as people used to say, a living sermon. They knew that many people would be more persuaded by example than by argument—that’s why they wrote Mill’s autobiography, an unusual choice for a philosopher. Look, they say, you can live differently. Here, see how I have lived. So can you. ’Tis not too late to seek a newer world.

It’s time we saw that living sermon in all of Mill’s most important works. Until we understand that, we have no true biography of the Mills. There isn’t even one that accounts for the marriage properly.1 (Even Phyllis Rose, who wrote a portrait of five unconventional Victorian marriages, called Harriet a “shrew”.) The only two books that do somewhat comprehend Mill and Taylor are intellectual biographies, written by academics. They are excellent, but not for a general audience.2

Just think what Mill, the most effective advocate for feminism in his generation, would make of this…

Because of Mill’s role in public debate today, biographers neglect their core task, which is, as Samuel Johnson said, “to lead the thoughts into domestick privacies, and display the minute details of daily life.” The enormity of Mill’s work and life and mind makes it hard to write anything other than a largely public chronicle. That’s what Richard Reeves, Mill’s most recent biographer (2007), does over five hundred pages, as Michael St. John Packe did before him (1954). Reeves covers the historical record—but he lacks imagination about Harriet, who he patronises.

Packe notes that Harriet’s ideas became “the most evangelical of Mill’s convictions”. He understands that she defined his ideas, even if she didn’t write them, though he is acute enough to see the many passages in Mill’s books that are, of course, passages by Harriet. Packe accepts that the ideas of On Liberty were mostly Harriet’s. But he didn’t write a joint biography. He didn’t properly trace the life in the work.

At least Packe is sympathetic. Reeves says Mill “lost his fabled powers of intellectual judgement” over Harriet. In one chapter, he gives more space to disagreeing with Packe and others than to allotting Harriet her share of the praise. In Reeves’ chapter about On Liberty, the Kingsley Amis novel Jake’s Thing is discussed for a whole page, while Harriet is only mentioned in passing. Remember, Mill said that most of the ideas in that book were Harriet’s. And Reeves gives Harriet a mere two paragraphs in his chapter on the Subjection. He correctly says her presence can be felt on every page. Odd, then, that she features so little in his account.

Samuel Johnson complained that eighteenth century biographers didn’t provide details of their subject’s life, but obscured everything in the mist of panegyric. Today we often have the opposite—biographies with so much careful detail, character gets lost in the crush of narrative, context, and side-taking. Johnson said biography should “enchain the heart by irresistible interest”. We are more often concerned to enchain the mind with thoroughness. Good biography needs both.

The side-lining of Harriet is why Mill’s biographers never quite enchain the heart. The love story is too much separated from the work.Until we restore Harriet and John’s life together to the heart of the story, we will never see Mill’s ideas for what they really are—not just a call to live differently, not just an argument to protect freedom, but a demonstration that it is possible to live differently and to flourish, spiritually, emotionally, as individuals.

I said earlier that John and Harriet’s story resembles Romeo and Juliet in its intensity. It resembles it, too, in the tragic ending. The Mills were only married for seven years before Harriet died, quite suddenly, and without warning, from a hemorrhage. For years they had both been ill, worried John would die prematurely from consumption. Then, when he finally retired, and they both seemed to be in good health, it was Harriet who died. All of a sudden, Mill was sitting alone in a hotel room, his wife’s body beside him. He was devastated. “The spring of my life is broken”, he said.

But this was not the end of their work. Mill vowed to further their joint causes. “The only consolation possible is the determination to live always as in her sight.” That was the animating spirit that ignited the movement for women’s suffrage. That was the fire that burned within while he wrote The Subjection.

The spring of my life is broken. Years earlier, as a young man trying to work out what he believed, Mill wrote a long essay evaluating his mentor, Jeremy Bentham. Reading Bentham transformed had Mill’s view of the world. He “formed a sovereign contempt for all previous moralists.” And yet, as he matured, Mill realised Bentham was too narrow. He was all logic, no poetry. Bentham was ignorant, said Mill, “of the deeper springs of human character.”

Harriet was that deeper spring for John. Sometimes the springs were so deep they escaped the paper record. That doesn’t mean we cannot see and credit her influence everywhere in his work. As Mill said,

When two persons have their thoughts and speculations completely in common; when all subjects of intellectual or moral interest are discussed between them in daily life… when they set out from the same principles, and arrive at their conclusions by processes pursued jointly, it is of little consequence in respect to the question of originality, which of them holds the pen.

Susan Okin puts it like this: “Until the 1960s, twentieth-century biographers of Mill, such as Ruth Borchard, Hayek, and Packe, had tended to accept Mill’s estimate of the great extent of Harriet Taylor's intellectual influence on him, especially Packe, p. 317, who talks as if she all but wrote all of Mill's major works except the Logic. In recent years, however, there has been considerable reaction against this view, from Jack Stillinger, who edited the earlier draft of Mill's Autobiography, H. O. Pappe, in a short work entitled John Stuart Mill and the Harriet Taylor Myth, Melbourne, 1960 and John M. Robson, in his study of Mill's thought, The Improvement of Mankind, Toronto, 1968. None of these writers disputes that Harriet Taylor was a very important part of Mill’s life, and that she provided him with the emotional well-being without which he may well not have been nearly so productive: what they are disagreeing about with the earlier critics, and with Mill himself, is that the principal ideas of his works were hers, not his.”

I like this piece, Henry. And I like the honorable exchange between Ontiveros and yourself in this comment section. Even if your argument is overcorrection, I'm okay with that as it seems to be pushing in the right direction.

If we take Mill seriously, "in history, as in travelling, men usually see only what they already had in their own minds; and few learn much from history, who do not bring much with them to its study", then our attempts at understanding the past will always miss the mark in one direction or the other.

Mill/Taylor are in a tough spot when in comes to Bentham and Utilitarianism. They have to carve a pathway between the structuralism of the 'innate principles' school and the Empiricism/Associationist worldview. In hindsight we have Darwin and Popper and others to give us a slightly more complete picture of the ideas in play. So there are moments where Mill/Taylor are almost utopian in the way they think about the future...they are living in a disagreeable modernity but hoping for a correction towards a more agreeable stasis in the future.

But their willingness to argue from both sides of the coin for each and every problem usually brings them back to the more palatable, real world situation. And the deep work they put into their ideas led them to little gems like this one from On Liberty, "...in the human mind, one sidedness has always been the rule, and many sidedness has always been the exception. Hence, even in revolutions of opinion, one part of the truth usually sets while another rises."

It's like an Escher in word form. But does it miss the mark?

I have not ignored Harriet Taylor, but I am wholly ignorant of her. Almost every post you send me scuttling off to add to the TBR pile. So much interesting stuff, so little time.