The rise and fall (and rise again) of Shakespeare's First Folio

The story of how people have respected and disrespected Shakespeare's First Folio, published four hundred years ago this week.

Housekeeping

In case you missed it—some recent articles on the Common Reader

Writing elsewhere

On The Books That Made Us I wrote about my abiding love of Samuel Johnson.

Book Club

There has been a suggestion for a meet-up in London to discuss Mill’s Autobiography. Let me know if you are interested.

The next bookclub is on 26th November, 19.00 UK time. We are reading Darwin. Selected Letters and The Origin of Species. For letters, any edition will do, and it’s less essential than Origin.

The rise and fall (and rise again) of Shakespeare's First Folio

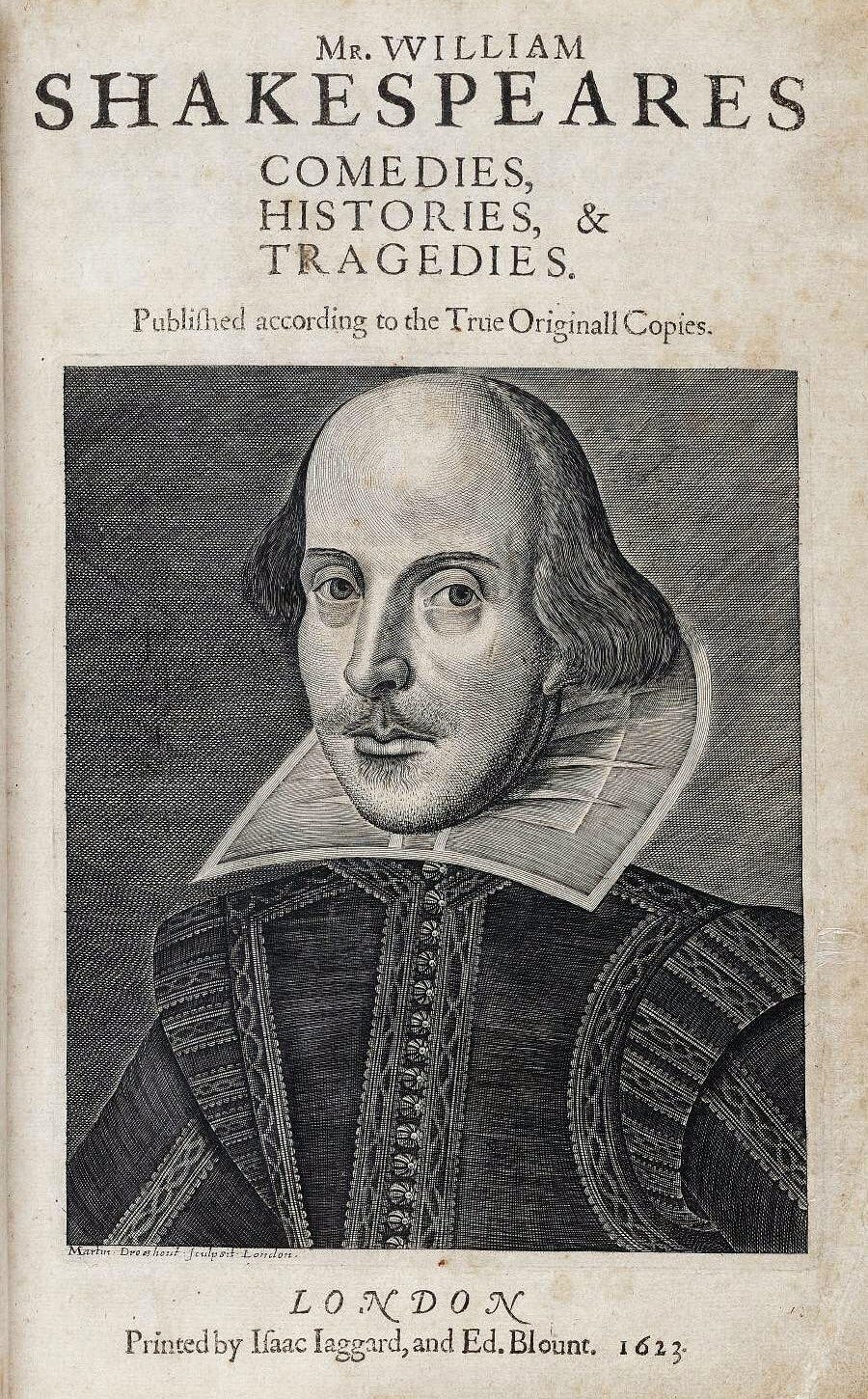

Shakespeare was the bestselling poet-playwright of the early seventeenth century, with nearly twice as many published quartos as the next most popular author. When the First Folio was published four hundred years ago on 8th November 1623 (the first collection of all his plays), the printer’s costs were £250—at the time, a shoemaker could make £4 a year, a goldsmith £5. Inevitably, at fifteen shillings, this was the most expensive playbook ever published, and the previous thirty years had seen many literary folios, including those of Ben Jonson and Montaigne. So, Shakespeare’s greatness was recognised early, by his sales, the large investment of his publishers, and the premium his works commanded. The First Folio was a publishing sensation. Shakespeare’s words were fixed in print.

But over the next century, the primacy of the First Folio went into decline. Theatre was banned in the Commonwealth (1649-1660), after the Civil War, and the restoration of the theatres in 1660 came with some obvious changes: moveable scenery, courtly acting styles, and women. Hamlet, Othello, Julius Caesar, and Henry IV part I were performed relatively uncorrupted. The actor Thomas Betterton was taught by someone who had seen original performances forty years earlier at the Blackfriars Theatre, so the tradition wasn’t entirely broken.

But the most significant changes were the edits made to the established text of the First Folio. William Davenant blended Measure for Measure and Much Ado About Nothing into a new play The Laws Against Love. Romeo and Juliet became a tragi-comedy. To Macbeth and The Tempest, he added music. Worst of all, Shakespeare’s language was simplified. As the scholar Russell Jackson says, in Davenant’s Macbeth “there is no crowding of image upon image, no jostling of the commonplace by the lofty.” It is a common mistake to think that neatness, balance, and structure are what makes art great. That’s why Dryden praised this execrable interference, because he thought Shakespeare was often “ungrammatical”, “coarse”, “affected”, and “obscure”.

Such simplifications (including cutting and adding characters and altering endings) made Shakespeare more populist: these poetasters blundered into great art and refigured it into the Restoration equivalent of Hollywood’s redemptive story arcs. And so we find Prospero no longer asking to be forgiven for his sins, but saying, “Henceforth this isle to the afflicted be/A place of refuge as it was to me.” Shakespeare had exposed the full depth and breadth of human experience; Davenant trashed all that for crowd-pleasing platitudes. In similar vein, Colley Cibber turned Richard III into a melodrama.

Chief of these dunces was Naham Tate, who took the vast, unbearable greatness of Lear and made it sentimental, moralising, and dull. Shakespeare’s play is one of the greatest tragedies in the Western canon, climaxing at the loss of Cordelia’s life to Lear’s selfish madness. Tate dumbed this down into a happy ending and made it relevant to contemporary themes of love and empire: “Divine Cordelia all the gods can witness/How much thy love to empire I prefer.” These witless pleasantries were assumed to be an improvement on the original and the now anonymous cant merchants were proud of their work.

At the same time, though, the early eighteenth century saw the start of a long, slow revival. Rowe and Warburton produced somewhat more original texts. Samuel Johnson continued this work with his customary vigour—his annotations are full of complaints about previous editors who “molested” the original text based on spurious knowledge or even ignorance of Shakespeare’s language. Having read Shakespeare obsessively since his childhood, and in careful, deliberate detail for his work on the Dictionary, Johnson had an unmatched expertise.

Johnson’s friend Garrick made his acting debut in Richard III and began the long restoration of Shakespeare to something more like his original state on the stage. The high praises Johnson gave to Shakespeare, and the efforts of Garrick in the theatre, meant that the canonisation his contemporaries had clearly assumed was finally underway. From now on, there really would be something sacrosanct about the original text. Still, Garrick made a farce out of The Taming of The Shrew and his Hamlet had the fight between Hamlet and Laertes before Ophelia’s death. There was work to do.

Romantic actors like Sarah Siddons and Charles Kean were more formal and mannered, trying to bring classical dignity to the now apotheosized author. They performed with statue-like poses, in “images of beauty and feeling.” These actors would seem stilted to us, like a procession of grand historical paintings, but they brought what Hazlitt called the “conflict of passions” back to Shakespeare.

The end of the nineteenth century saw a new sort of naturalism, as with Beerbohm Tree’s famous production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream where real rabbits hopped about the stage. This was the culmination of the long journey back to originalism. Henry Irving and Ellen Terry returned to the Shakespeare text of Richard III (ditching Cibber), restored the final act of The Merchant of Venice (long neglected), and produced less popular plays like Cymbeline.

This revival reached its head after the First World War with Frank Benson’s company at Stratford. Benson had acted with Irving and Terry and continued this originalism with Shakespeare tours and a Stratford festival, first established in 1879. In the 1920s, with the first permanent company at Stratford, the forerunner of the RSC, William Bridge-Adams produced Shakespeare uncut, including the first full-text Hamlet, in a move away from star-led productions.

Everything changed again after the Second World War when, in 1946, Barry Jackson (who staged modern-dress Shakespeare productions) took over and refused to employ the old guard. The classical style was out. But although it has subsequently been acceptable to stage Shakespeare with any interpretation, what has long been secure is the idea that while you might make cuts for the sake of performance, there is only one text, one true version of the plays, which comes from those early bestselling quartos and the First Folio. Editors still have to choose how to resolve differences between quarto and folio editions, but they choose between the different ways in which Shakespeare wrote, without interloping their own mundane ideas.

The reason for this reverence is simple, and best expressed by Samuel Johnson: Shakespeare’s “chief skill was in human actions, passions, habits… his works may be considered a map of life.” Without the crowding passions and the jostling language, without the mess so many generations tried to smooth out, we lose what makes Shakespeare great—the conflict of passions and the map of life.

is there a good source to explore this story further...? great piece, thank you

Thoughts on Harold Bloom's The Invention of the Human?