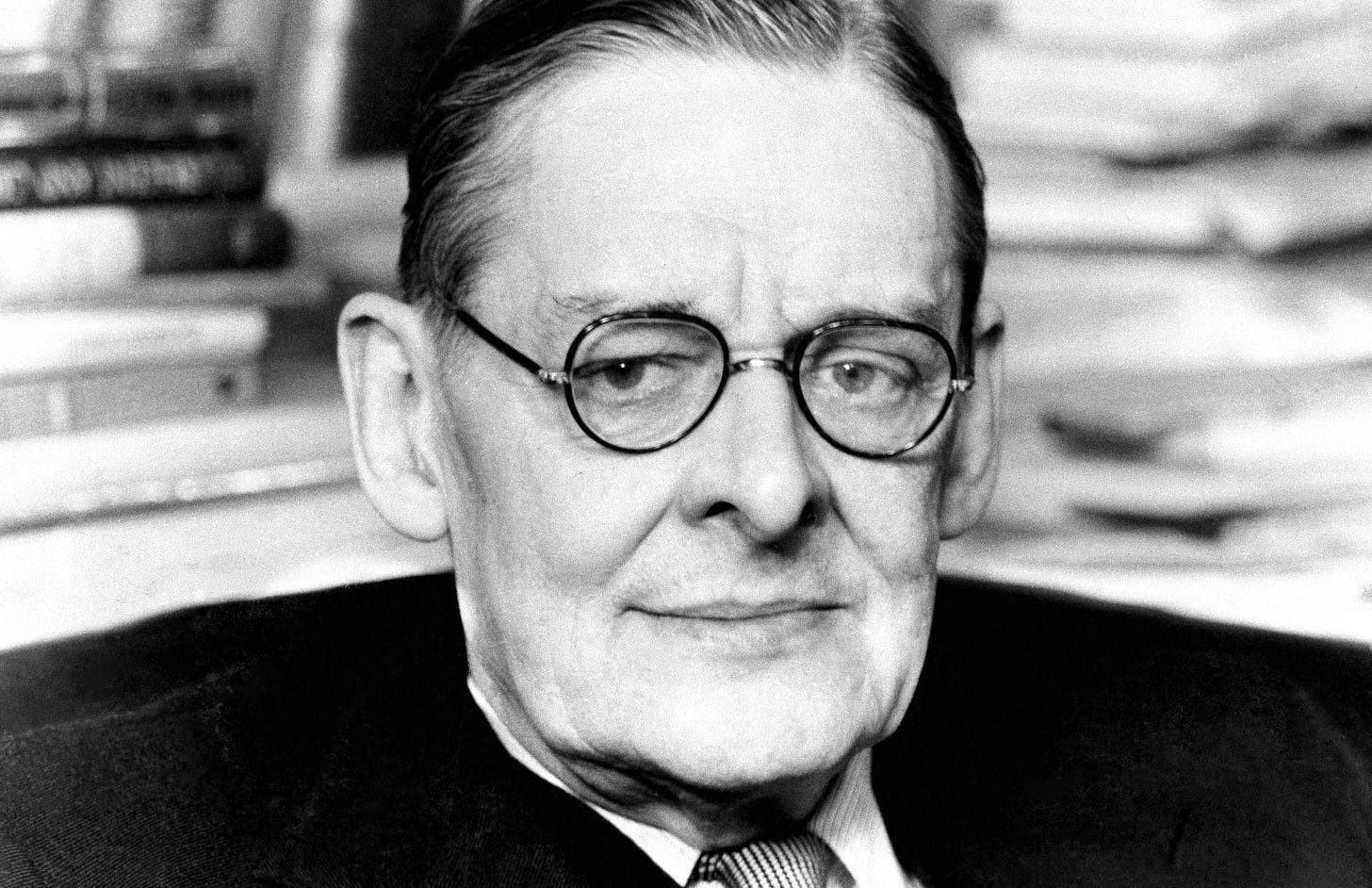

T.S. Eliot and the Whitsun fire

To be redeemed from fire by fire.

And they were all filled with the Holy Ghost

This day’s bread, preached John Donne on WhitSunday in 1625, is to meditate upon the holy Ghost. Whitsun, or Pentecost, which falls today, is the fiftieth day after Easter. It marks the day when the Holy Spirit descended upon Jesus’ disciples, narrated in Acts 2:1-4.

And when the day of Pentecost was fully come, they were all with one accord in one place. And suddenly there came a sound from heaven as of a rushing mighty wind, and it filled all the house where they were sitting. And there appeared unto them cloven tongues like as of fire, and it sat upon each of them. And they were all filled with the Holy Ghost, and began to speak with other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance.

The locals think the apostles are drunk, but Peter stands up to remind them of the prophet Joel’s prediction—

And it shall come to pass in the last days, saith God, I will pour out of my Spirit upon all flesh: and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy, and your young men shall see visions, and your old men shall dream dreams…And I will shew wonders in heaven above, and signs in the earth beneath; blood, and fire, and vapour of smoke: The sun shall be turned into darkness, and the moon into blood…

In his Four Quartets, T.S. Eliot showed us his visions and dreams. These splendid late poems made a symbolism by combining Dante’s lights and the Pentecostal fires. What he exhorts is that we can be comforted by the reproof of our sins: that we must be redeemed from fire by fire. In this way, judgment becomes consolation, and suffering becomes redemption.

With flame of incandescent terror

In the Gospels (Matthew, 3:16; John, 1:32) the Holy Ghost is depicted as a dove (“he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove”). This is the image with which Eliot begins the fourth section of ‘Little Gidding’, which is a Pentecostal poem.

The dove descending breaks the air

With flame of incandescent terror

Of which the tongues declare

The one discharge from sin and error.

The only hope, or else despair

Lies in the choice of pyre or pyre—

To be redeemed from fire by fire.Who then devised the torment? Love.

Love is the unfamiliar Name

Behind the hands that wove

The intolerable shirt of flame

Which human power cannot remove.

We only live, only suspire

Consumed by either fire or fire.

Eliot thought this was the best part of ‘Little Gidding’, although he had worried about the attempt to make it sound like seventeenth century verse. He will have been thinking of George Herbert, too.

Listen sweet Dove unto my song,

And spread thy golden wings in me;

Hatching my tender heart so long,

Till it get wing, and flie away with thee.

Where is that fire which once descended

On thy Apostles? thou didst then

Keep open house, richly attended,

Feasting all comers by twelve chosen men.

“I steeped myself in Dante’s poetry”

The other great poetic spirit that sits behind this work, of course, is Dante, whom TSE read in the Temple Classics edition, with Italian on one page and English prose on another. When he puzzled out specially important passages to himself, he memorised them. Here’s what he said in his essay about Dante.

for some years, I was able to recite a large part of one canto or another to myself, lying in bed or on a railway journey. Heaven knows what it would have sounded like, had I recited it aloud; but it was by this means that I steeped myself in Dante’s poetry.

Dante’s influence shows up right at the start of ‘Little Gidding’ when the “primavera sempiterna” (eternal spring), becomes,

Midwinter spring is its own season

Sempiternal though sodden towards sundown,

Suspended in time, between pole and tropic.

Standing outside the chapel of Little Gidding, where Charles I once prayed, and which was destroyed by the Cromwellians, Eliot invokes the renewing spring wind of Whitsun in the dead of winter.

When the short day is brightest, with frost and fire,

The brief sun flames the ice, on pond and ditches,

In windless cold that is the heart’s heat,

Reflecting in a watery mirror

A glare that is blindness in the early afternoon.

And glow more intense than blaze of branch, or brazier,

Stirs the dumb spirit: no wind, but pentecostal fire

In the dark time of the year.

All of this fire and ice echoes Dante, as well as the Bible. These are core themes of Four Quartets: the renewal of death, in my beginning is my end, “And all is always now”—, ideas that Eliot has been preoccupied with since he wrote “April is the cruelest month.”

In the dark cold time we look forward to the renewal of the Holy Spirit, knowing midwinter is the time of Jesus’ birth. Herrick expresses the same thing in his “Christmas Carol”, which Eliot quoted in a Christmas card. Christopher Ricks notes, in his footnotes to this section of the poem, (you simply have to read the Ricks edition), that it is a common conceit of C17th verse to make a spring of deep winter, as this is the time of Christ’s birth. (Poem at the footnote.)1

The dark dove with the flickering tongue

In the next section of the poem, the Dantean fire becomes the Blitz bombs. Here Eliot is matching the hell fire of the Blitz to the flaming tongues of Acts 2.

In the uncertain hour before the morning

Near the ending of interminable night

At the recurrent end of the unending

After the dark dove with the flickering tongue

Had passed below the horizon of his homing

While the dead leaves still rattled on like tin

Over the asphalt where no other sound was

Between three districts whence the smoke arose

I met one walking

Now Eliot meets his Virgil, his poetic guide, who tells Eliot he will “disclose the gifts reserved for age/ To set a crown upon your lifetime’s effort.”

The gifts of age are: the cold friction of expiring sense; the conscious impotence of rage; and, finally, “the rending pain of re-enactment/ Of all that you have done, and been.”

This last point is the start of wisdom.

From wrong to wrong the exasperated spirit

Proceeds, unless restored by that refining fire

Where you must move in measure, like a dancer.

The refining fire is pentecostal, of course. In possession of this wisdom, Eliot begins the next section of the poem, saying,

There are three conditions which often look alike

Yet differ completely, flourish in the same hedgerow:

Attachment to self and to things and to persons, detachment

From self and from things and from persons; and, growing between them, indifference

Which resembles the others as death resembles life,

Being between two lives — unflowering, between

The live and the dead nettle.

To make sense of this—especially that awkward word, indifference—let’s turn back to that Whitsun sermon, preached by John Donne in 1625, which I quoted at the start.

Consolation from the Holy Ghost

Acts 2.21 (“And it shall come to pass, that whosoever shall call on the name of the Lord shall be saved”) is echoed in Donne’s sermon. To day if ye will heare his voice today ye are with him in Paradise; For, wheresoever the holy Ghost is, he creates a Paradise. The day is not yet over, Donne says; you can still be with him in Paradise. God carries back the shadow of your sun dial if you will take knowledge that when he comes he Reproves the world of sin.

But, according to Donne, the Holy Ghost is sent as the Comforter. Reprove and comfort together? Can we be comforted by a reprimand? Yes, says Donne. So long as the reproof does not lack charity.

Christ came to us as the mediator between man and God. And there is our first comfort, says Donne, in knowing that Christ is God. As such he must be a Judge, he must Redeem us, which is a reproof; but it is the presence of the Holy Ghost which makes it a comfort. When we become our own judge, we can be redeemed, and so judgement is a comfort.2 So it becomes a state of transformation to suffer. (This is the sort of passage that makes Donne’s sermons a kind of poetry.)

This Consolation from the Holy Ghost makes my mid-night noone, mine Executioner a Physitian, a stake and pile of Fagots, a Bone-fire of triumph; this consolation makes a Satyr, and Slander, and Libell against me, a Panegyrique, and an Elogy in my praise; It makes a Tolle an Ave, a Væ an Euge, a Crucifige an Hosanna; It makes my death-bed, a mariage-bed, And my Passing-Bell, an Epithalamion. In this notion therefore we receive this Person, and in this notion we consider his proceeding, Ille, He, He the Comforter, shall reprove.

The reproof is not a chiding, it is not a sharp increpation, a bitter proceeding, but instead happens by inlightning and informing, and convincing the understanding. The reproof is literally that: re-proof, re-proving, re-arguing, placing truth against opinion. Hence: the reproofe must lie in argument, not in force. This resembles Donne’s notion of truth and opinion. Opinion lies in between knowledge and ignorance, he says. Knowledge excludes doubting; ignorance excludes indifference.3

Now, remember Eliot, who said that growing between attachment and detachment was “indifference/ Which resembles the others as death resembles life.”

For Eliot and Donne, receptivity to reproof is the beginning of allowing the Spirit to purify you with the comforting fire, whereas indifference is a spiritual death: the purifying death of the Whitsun fire, of the Dantean suffering, can be the start of a new life.

The fire and the rose are one

At the end of ‘Little Gidding’, Eliot invokes eternal time.

What we call the beginning is often the end

And to make an end is to make a beginning.

Redemption comes from sacrifice, life from death and death in life. Suffering, relived through religious life (as happened at the secluded religious community at Little Gidding in the seventeenth century) is how we ascend, Dante-like, to spiritual purity.

any action

Is a step to the block, to the fire, down the sea's throat

Or to an illegible stone: and that is where we start.

We die with the dying:

See, they depart, and we go with them.

We are born with the dead:

See, they return, and bring us with them.

“Any action is a step to the fire”—, to what Donne would call the comfort of reproof through the Holy Ghost. Reliving this through the Church every year “we are born with the dead”. In ‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’, Eliot says it is a sense of the timeless and the temporal together that makes a writer.

This poem is a quest. A quest through time, through religion, a spiritual journey, to pass through the midwinter and the purifying fire, through the comforting reproof of the Pentecost and the Blitz, and to arrive out of eternity in history.

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

The spiritual quest must involve a “dark night of the soul”. Echoing St. John of the Cross, Eliot wrote in ‘East Coker’,

In order to arrive there,

To arrive where you are, to get from where you are not,

You must go by a way wherein there is no ecstasy.

In order to arrive at what you do not know

You must go by a way which is the way of ignorance.

In order to possess what you do not possess

You must go by the way of dispossession.4

Eliot has quested as a poet, as a Christian, as a simple man. He has quested through the dark night of the soul, the emptiness of dispossession, and he ends his journey after suffering with purification and light.

Eliot’s final lines unite the pentecostal, the Dantean, and the poetic. (In East Coker, he says the purgatorial fires are roses, just as in the Blitz section he called the bomb fire burnt roses, uniting the reproof and comfort of the Holy Ghost.)5

All manner of thing shall be well

When the tongues of flames are in-folded

Into the crowned knot of fire

And the fire and the rose are one.

As Ricks notes, Dante is the final echo.

Oh grace abounding, wherein I presumed to fix

my look on the eternal light so long that I

consumed my sight thereon!

Within its depth I saw ingathered, bound by

love in one volume, the scattered leaves of all

the universe;

substance and accidents and their relations, as

though together fused, after such fashion that

what I tell of is one simple flame.

The universal form of this complex I think that I

beheld, because more largely, as I say this,

I feel that I rejoice.

Dark and dull night, fly hence away,

And give the honor to this Day,

That sees December turn'd to May.

If we may ask the reason, say:

The why, and wherefore all things here

Seem like the Spring-time of the year?

Why does the chilling Winter's morn

Smile, like a field beset with corn?

Or smell, like to a mead new-shorn,

Thus, on the sudden?

Come and see

The cause, why things thus fragrant be:

'Tis He is born, whose quick'ning Birth

Gives life and luster, public mirth,

To Heaven and the under-Earth.

“…so there is Spiritus in Spiritu, a Holy Ghost in all the holy offices of Christ, which offices, being, in a great part, directed upon the whole world, are made comfortable to me, by being, by this holy Spirit, turned upon me, and appropriated to me; for so, even that name of Christ, which might most make me afraid, the name of Judge, becomes a comfort to me.”

Of the three ways of knowing the divine—reason, faith, opinion—Donne dislikes opinion, which is a fancy, like waking dreames, and which receives too much honour if it is reproved. Disputing an opinion is like blowing on embers.

And so, that which was but straw at first, by being thus blown by vehement disputation, sets fire upon timber, and drawes men of more learning and authority, to side, and mingle themselves in these impertinencies.

As fancies grow into opinions, men think they have reasons for their opinions, but they do not, and this is the route to division. Holding an opinion long enough to believe it is like coming to believe your own lies.

Slightly earlier are these lines

I said to my soul, be still, and wait without hope

For hope would be hope for the wrong thing; wait without love,

For love would be love of the wrong thing; there is yet faith

But the faith and the love and the hope are all in the waiting.

Wait without thought, for you are not ready for thought:

So the darkness shall be the light, and the stillness the dancing.

Whisper of running streams, and winter lightning.

The wild thyme unseen and the wild strawberry,

The laughter in the garden, echoed ecstasy

Not lost, but requiring, pointing to the agony

Of death and birth.

In East Coker, TSE wrote:

The whole earth is our hospital

Endowed by the ruined millionaire,

Wherein, if we do well, we shall

Die of the absolute paternal care

That will not leave us, but prevents us everywhere.The chill ascends from feet to knees,

The fever sings in mental wires.

If to be warmed, then I must freeze

And quake in frigid purgatorial fires

Of which the flame is roses, and the smoke is briars.

I used to awaken, and read from the Four Quartets every morning. I love the words.

Thank you. Comes after my partner went to a reading of two of the quartets last night, & we discussed their relation to Acts this morning. I can't get enough of reading his lines.