What I Learned from Reading Peter Pan to my Children.

The Wisdom of Wendy Darling and the Joy of Growing Up.

I have been reading Peter Pan to my children. Does parenthood offer greater privileges?

Some writers stay brightly on the surface, and some go down deep into things without giving a damn, as P.G. Wodehouse said. Great authors, of course, can do both at once, which is precisely what makes Peter Pan so pleasurable to read aloud to little ones.

The children are aflame with tension about pirates and poisons, fairies and fights, while I am able to revel once more in a land before time ran to the clock. Barrie flies us delightfully over a story of the gentle Never-bird and Tinker Bell’s wicked schemes and Tiger Lilly climbing aboard the Jolly Roger with knife in her mouth, and all the while the reading parent pines for time lost, time they cannot hope to regain.

Across the sea I have left behind me a copy of the complete plays of J.M. Barrie, many of which are not much missed, though there are several splendid works, including the one act plays, a dead form now at which Barrie sometimes excelled. But who can be without a copy of Peter Pan? We obtained one from the library in short order on our arrival in the USA.

Who does not carry some sense within them of what it means to fly to Neverland, to fight Captain Hook, to hear the tick-tick-tick of the crocodile?

Which of us does not know what it means to dream of such a place, a place where time does not flow constantly like the breeze?

It is the constant waking nightmare of adult life that the clock only runs one way—that time cannot be restored, even by art. O tell me where all past times are, Donne implores. It is this ability to capture so precisely the differences between the adult and children’s sense of time that makes Peter Pan one of the most sophisticated works of fiction written for children in English.

It is charming, like Wind in the Willows; and it is clever, like Alice; and it is a world of itself, like Narnia; and it is full of intelligent whimsy, like Pooh; but it is in a class of its own as a work of dual appeal to children’s and adults’ concerns. Perhaps no other book than Gulliver’s Travels has traversed those two foreign worlds so often and with such success.

Too many adults forget the fluid contiguity between the imagination and reality that defines children’s lives, leaving them (as Tolkien complained) unable to enter the dream of the poem, unable to enter the world of the child. If we take Peter Pan seriously—not seriously as adults take things, but seriously as an experience in itself—we can perhaps regain entry, if only for a while.

Barrie’s literary merits are technical as well as emotional. Peter Pan is a work of meta-fiction. Just as the child can easily step outside the pretence of pretending to instruct someone how to play, what to do, and justify breaking the fourth wall by saying “this is all in the game”, so Barrie constantly intrudes upon his narrative to explain: moving time backwards and forwards, telling us what he does and does not know about his characters, explaining that Neverland is quite real, but also that it is made out of John, Michael, and Wendy’s imaginations.

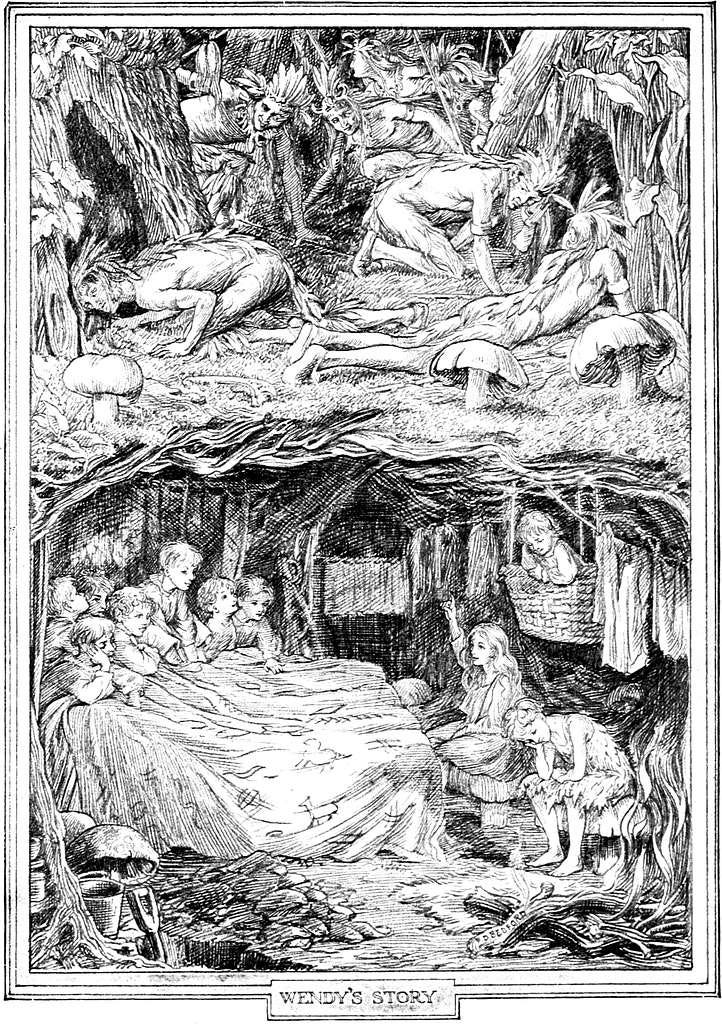

This is reflected in the way the children play. The Wendy house is built around Wendy while she lies (not quite) dead from the arrow—, and she instructs them from her unconsciousness, just as a child would in a game, being both the real and the imaginary at once, and seeing no contradiction in that mingled state. The joy is not merely that of seeing how well Barrie understands that way children play, (singing their instructions from their coma, pretending not to pretend,—which is part and parcel of “how it works in the game”), it is the joy, too, of seeing that childhood is a rehearsal for life, a state of both the real and the imagined.

The games the children play in Peter Pan are all preparations for the real work of their lives; they play at being grown up. That is what Peter refuses to take seriously.

“Peter, what is it?”

“I was just thinking,” he said, a little scared. “It is only make-believe, isn’t it, that I am their father?”

“Oh yes,” Wendy said primly.

“You see,” he continued apologetically, “it would make me seem so old to be their real father.”

“But they are ours, Peter, yours and mine.”

“But not really, Wendy?” he asked anxiously.

“Not if you don’t wish it,” she replied; and she distinctly heard his sigh of relief.

Not if you don’t wish it. Whether you are in the real world or the imagined one, you must believe, you must wish it, if it is to be really real. Neverland is where children learn to grow up. That is why Barrie ends the story with a chapter about Wendy’s getting married and having children and grandchildren of her own.

Peter has a tremendous, important appeal, but he is ultimately a warning figure, a fancy for youth, a stage of development, not a state of being.

Children begin to enjoy this story when they are on the cusp of knowing both sides of Peter—, his great appeal and his terrible limitations. To meet a real Peter Pan in real life (someone like Edward VIII) is a horrible thing. Children know that Peter is not quite to be trusted. They want him to defeat Captain Hook; they also want Wendy to return to her mother, and to become a mother.

Barrie understands children remarkably well, as my daughter told me. He knows they are “gay and innocent and heartless” but also that they are destined to grow, that they both do and do not want to become adults.

That is why Peter is so fickle. “Of course Peter promised; and then he flew away.” What wins out in this story is not the pleasure of Neverland, but the certainty of a mother’s love. The true, original title is Peter and Wendy, and she is our real hero.

But the years came and went without bringing the careless boy; and when they met again Wendy was a married woman, and Peter was no more to her than a little dust in the box in which she had kept her toys. Wendy was grown up. You need not be sorry for her. She was one of the kind that likes to grow up. In the end she grew up of her own free will a day quicker than other girls.

Perhaps I am fanciful, but I cannot help but hear the echo of Proverbs 8 in this paragraph. Those verses begin:

Doth not wisdom cry? and understanding put forth her voice? She standeth in the top of high places, by the way in the places of the paths. She crieth at the gates, at the entry of the city, at the coming in at the doors. Unto you, O men, I call; and my voice is to the sons of man.

Here we can see a parallel of the story of Peter and Wendy, in which we must untangle whether he is crying wisdom, or she is, and where the coming in at doors (the flying in through the window) and the places of paths (Neverland, in which the crocodile tracks the Indians who track the pirates who track the boys who track Peter who tracks Wendy) all lead to Wendy standing and calling to the sons of man (the lost boys).

Wendy must choose wisdom over Peter. That is what he could learn from her, were he able to listen to any mother: “All the words of my mouth are in righteousness; there is nothing froward or perverse in them. They are all plain to him that understandeth, and right to them that find knowledge.” That is Wendy to a word. Of course, the question “why are you crying boy?” is ultimately answered for Peter—, he cries because he cannot grow up, cannot find wisdom, cannot follow the words in Wendy’s mouth.

In the end, the lost boys do follow Wendy on the right path. “I lead in the way of righteousness, in the midst of the paths of judgment: That I may cause those that love me to inherit substance; and I will fill their treasures.” Their treasures are families and office jobs; those that love them inherit their stories.

That passage I quoted above echoes Proverbs 8 in several points, but most strongly with the mention of dust.

I was set up from everlasting, from the beginning, or ever the earth was. When there were no depths, I was brought forth; when there were no fountains abounding with water. Before the mountains were settled, before the hills was I brought forth: While as yet he had not made the earth, nor the fields, nor the highest part of the dust of the world.

This is what Wendy and the boys must learn. Wisdom came before Neverland.

What looks like the utopian creation, the garden of childhood, is a later invention. All children are eventually called out of their world to the world of wisdom, the world of the real.

Now therefore hearken unto me, O ye children: for blessed are they that keep my ways. Hear instruction, and be wise, and refuse it not. Blessed is the man that heareth me, watching daily at my gates, waiting at the posts of my doors. For whoso findeth me findeth life.

Wendy calls to Peter like this, so does Mrs. Darling. But he refuses. He flies away. He repeats the cycle again and again. He is trapped and Wendy is free. He does not find life.

Barrie’s moral lesson is not exactly modern. We no longer approve of stories written to exult the Wendy-type girls, the natural mothers. We no longer approve of these Victorian Values.

We preach modernity just as strongly as Barrie preached the wisdom of the mother, of course. Modern children’s authors often say they no longer write with a view to moralising. It’s not true. Their books are always pushing a liberal ideology on children, it just hides behind acceptability, whereas old-fashioned moralising now seems, well, old-fashioned.

Wendy is the hero we don’t want to celebrate. Voluntary childlessness is a sustained part of modern life. People are increasingly cutting off their relatives. People talk Panishly about “adulting” and their longer and longer youths. We cannot doubt the valid decisions many individuals are making; nor can we doubt the many sad losses this entails. All those dreams not dreamed, all those children not delighted, all those parents who do not get to hear their little ones gasp and gurgle while they take a nostalgic pleasure in that delight.

And yet, the story lives. After a century, Peter and Wendy are at no risk of vanishing from childhood. Perhaps they are known more through common knowledge and movies than the book, perhaps not. Barrie’s excellent prose is not what children are used to now, though I suspect it is not what children were ever used to. This is the sort of book that was written to be read aloud. Paragraphs like these are supposed to be heard while you loll in bed, your little fingers hanging expectantly at your curious lips, your feet swinging with confusion, intrigue, suspense, and enchantment.

It is the nightly custom of every good mother after her children are asleep to rummage in their minds and put things straight for next morning, repacking into their proper places the many articles that have wandered during the day. If you could keep awake (but of course you can’t) you would see your own mother doing this, and you would find it very interesting to watch her. It is quite like tidying up drawers. You would see her on her knees, I expect, lingering humorously over some of your contents, wondering where on earth you had picked this thing up, making discoveries sweet and not so sweet, pressing this to her cheek as if it were as nice as a kitten, and hurriedly stowing that out of sight. When you wake in the morning, the naughtiness and evil passions with which you went to bed have been folded up small and placed at the bottom of your mind and on the top, beautifully aired, are spread out your prettier thoughts, ready for you to put on.

Barrie takes no pains to make his writing childishly simple. He uses words like precipitate, miasma, impudence, pestilent; he makes long, involved similes; he talks about public schools as if all his readers attend one; he frequently writes sentences as complicated as those you might expect to find in Dickens.

He writes like he is talking directly to children, the great author who happens to be in the room with you. That is, of course, how the book happened to be written, and if it feels sometimes like it is still living in Edwardian England that only adds to the mysterious appeal.

The past is a Neverland of its own, and inducting children into the strange, inaccessible ways of wisdom that they knew then, and which we are surprised to see we often still know now, (do not good mothers still spend time organising their children’s minds? don’t all little ones have an imagined world that can be entered simply by hanging a tablecloth over some chairs?), is part of showing them the importance of Peter Pan, the joy of growing up, the reason why they all pretend to be mothers and fathers in the first place.

It is the genius of J.M. Barrie to afford parents now, a century after he wrote, this privilege of watching their own children fly off to Neverland in their minds, just as we once did, just as we hope our grandchildren one day will fly.

It catches in our throat to admit it as we turn the final page, but what we learn from reading Peter and Wendy in middle age, watching our children waking up a little more to wisdom, is that for them to grow up might break our hearts—but it will not be a tragedy.

To grow up will be an awfully big adventure.

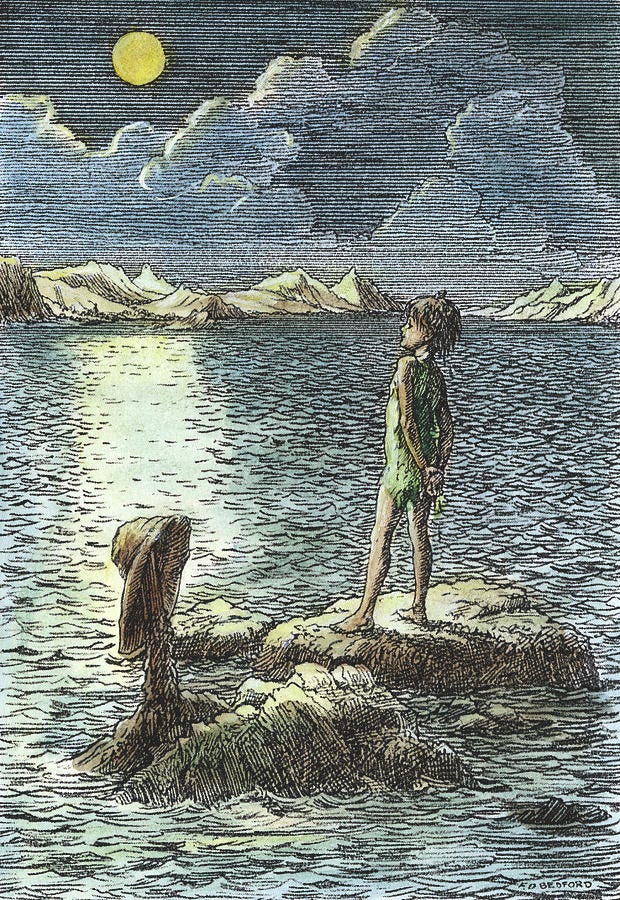

All of the illustrations used here are by F.D. Bedford, from the 1911 edition.

Excellent stuff. Nobody else is writing stuff like this. The Proverbs connection is very interesting. You've made me think about Peter Pan's refusing Wisdom. It's pagan of him, really. He's not called Pan for nothing.

The idea that mothers "clean out their children's minds" every night after they fall asleep stabs me in the heart every time I read it.

When I read modern children's books, my first question is always "was this written for children or for parents?" The best ones were written for children, but most were written for parents. So many are parenting manuals in disguise - a children's book about a child having a tantrum is really a parenting guide about how to handle a tantrum, etc. I'm not opposed to educating parents, but this is such an odd way to do it. Pre-WW2 children's books, especially the British ones, were 100% for children and are fantastically weird as a result.