What is spite?

A response to Hollis Robbins

In her ‘Notes on Spite’, Hollis Robbins (@Anecdotal) has suggested a productive new area for enquiry. What are the great works of art and literary criticism about spite? Hollis says “Spite may be the most undertheorized force in creative achievement.” Is that because spite is so hard to define? Even Johnson could only manage a string of epithets: “Malice; rancour; hate; malignity; malevolence.”

Spite is a species of hate, somewhere between revenge and contempt, in which our scorn for an enemy, pest, nemesis, or rival is made into a productive capacity, overwhelming us by becoming the motivating energy of action. Spite ruins mediocrities, but sets genius alight with a brilliant fire that sustains itself by consuming itself, attracting more and more fuel as it becomes notorious to others and preoccupying to the hater.

Spite is the release of unreasonable feeling; it is a partisan, chauvinist, personal expression; spite pretends to principle; alas, it has none. Politics is the great art of spite, followed by poetry, the allocation of capital, and family feuds. None of these is primarily, or purely, an art of spite, but each has the greatest potential to achieve something significant for the sake of malice towards another person. Some spites are general, as in the rage of party politics, the bigotry of policy, but all have some personal correspondence. We never hate entirely in the abstract. Spite is a kind of desire, the lust of despising, the thirst of dismissal.

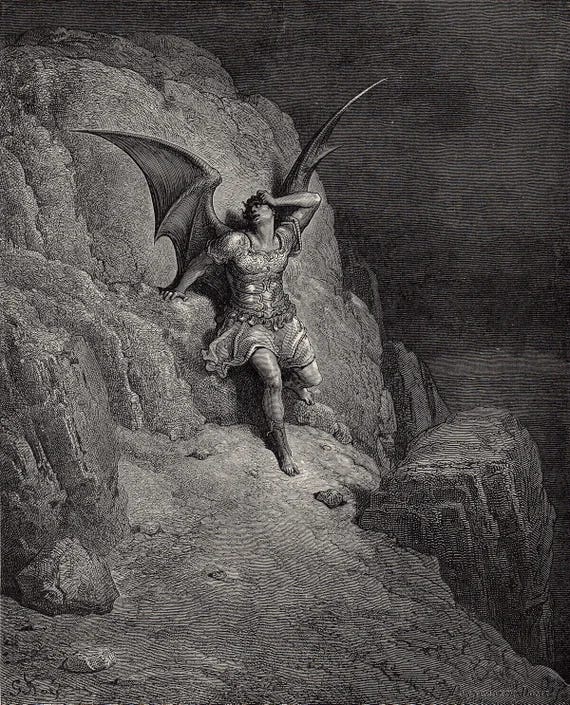

There is a canon of obviously spiteful literature, such as the Dunciad and The Bickerstaff Papers, but a great deal of the traditional canon is full of spite, too: parts of Dante, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Goethe, Gogol, Hans Christian Andersen, Zola, Hazlitt, Bronte, and Grimm; and so much of Shakespeare: what is Hamlet but a study of spite? (“The time is out of joint: O cursed spite, That ever I was born to set it right!”); then there is Iago, Edmund, Romeo killing Tybalt, Beatrice (“kill Claudio!”), Bertram, Portia—, indeed, the great achievement of The Merchant of Venice is to show that the spite which underlies traditional comedy like The Comedy of Errors can be brought to the surface, viciously, unrelenting, and the play can still end with the final act where all are married (Antonio aside). We have a great tolerance of spite, even when it exposes itself and all our hypocrisy. Paradise Lost is the great epic of spite, providing this whole area of study with its epigram: “Done all to spite/The great Creator.” A motto for our envious, entitled, rash, and bloody times! Milton’s poem is often about spite, and provides another good definition: “the hateful siege/Of contraries: all good to me becomes/Bane.”1

Spite is the great exposer of the biographical nature of life. So much that we do, we do for personal spite. So much of history and literary study and politics is the study of personality. Gulliver’s Travels understands this, constantly pointing to the role of petty temperaments in the discussion of grand ideals. In her ‘Notes on Spite’, Hollis Robbins (@Anecdotal) admits that spite is biographical.

The biographical record systematically obscures spite’s role because spite-driven creators rarely advertise their motivations.

Despite her obvious talents, Hollis is one of those who dislikes biography. But nothing else can make a proper study of spite: even those political commentators who disagree with the great man theory of history will note, every day, the role of interpersonal rivalry in the making of history. (Even literary theorists must accept that authors are the fount of literature when it is their work under discussion; which of them does not make a worship of Raymond Williams or Frederic Jameson?) I cannot think of a great biography that does not, in some manner more or less subtle, expose the role of spite in the writer’s life. Indeed, the great works of spite often make the display of spite so obvious we look right past it, as Hollis says.

The acknowledgement of spite as a great force to be theorised is the acknowledgement that man is a biographical animal, that biography is among the greatest critical arts. Perhaps there can be no true theory of spite: it is too personal.

And, slightly further down,

But what will not ambition and revenge

Descend to? Who aspires, must down as low

As high he soared; obnoxious, first or last,

To basest things. Revenge, at first though sweet,

Bitter ere long, back on itself recoils:

Let it; I reck not, so it light well aimed,

Since higher I fall short, on him who next

Provokes my envy, this new favourite

Of Heaven, this man of clay, son of despite,

Whom, us the more to spite, his Maker raised

From dust: Spite then with spite is best repaid.

I never thought of spite before as you've laid it out. I think spite is a form of schadenfreude where you are the cause of the "schaden."

Satan gets back at God by messing with Adam and Eve not merely by declaring it's better to rule in hell.

Thanks for this essay, Henry.

How interesting! And thought provoking. I have always thought of spite as beneath us, low, ignoble. Something to be ashamed of indulging in… Yet what else is revenge? Liked your examples.