When life is too much like a pathless wood

England, why England?

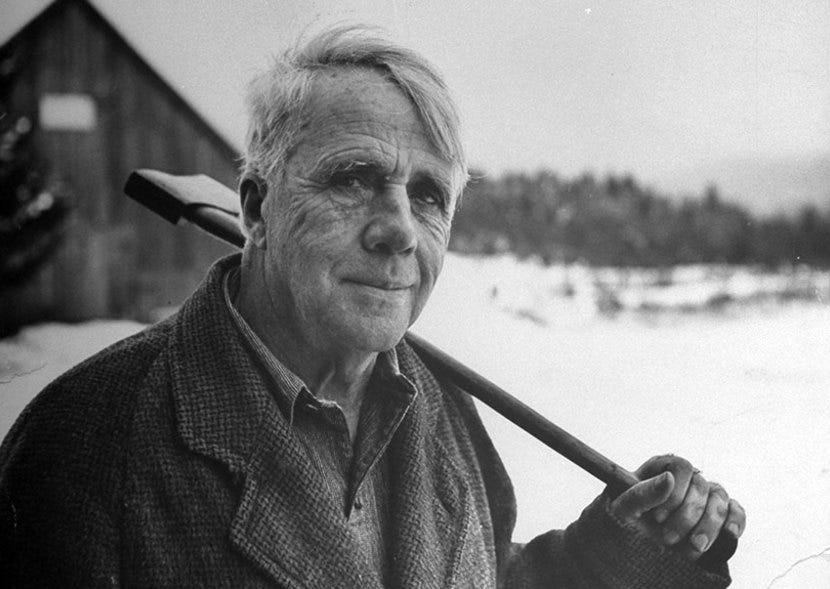

A few weeks ago, I wrote about Robert Frost’s late start as a poet. This is a companion piece about why he moved to England, and what his poems tell us about that strange episode in his life.

But why did Robert Frost move to England? Biographically, several answers can been given. His wife Elena wanted to go. She dreamed of living under thatch near Stratford. America had a paltry poetic culture and Frost needed to be at the heart of things. They simply wanted a change and flipped a coin for England or Vancouver. All of these explanations are true, but they are not all of the truth.

Frost had been a teacher, and a poultry farmer, living off a small income from his grandfather’s inheritance. This was limiting, trapping him up at the farm with little money. But it also freed him up to write poetry. And he did write, perhaps a hundred poems. He was, however, a natural discontent. Unhappy childhood, melancholic tendencies, difficulty sticking at anything. He chose to drop out of university twice. And he submitted relatively few of his poems to magazines.

He needed to be shaken out of himself.

Frost wrote about being shaken out of a reverie of melancholy in two of his most well known poems, “Stopping by Woods” and “Dust of Snow”.

The way a crow

Shook down on me

The dust of snow

From a hemlock treeHas given my heart

A change of mood

And saved some part

Of a day I had rued.

Something like this is what happened to Frost in England. Shortly after arriving there, he sat on a gate in a field, surrounded by mist; he later wrote a short poem about the experience in a letter. It is notable because it contains the first version of a line he used in “Birches”, but also because it expresses the same mood, the sense of being trapped in himself, needing to be shaken out.

This theme is there in the very first poem of A Boy’s Will, Frost’s first published collection.

“Into My Own” is about Frost’s desire to “steal away” into the “vastness” of a group of dark trees, which he wishes would stretch away to the edge of doom. If his loved ones followed him, he says,

They would not find me changed from him they knew

Only more sure of all I thought was true.

Several core traits of Frost’s work can be seen here, most notably the Dantean “dark forest”. But look too at the word “of” in the final line. In an earlier draft (rejected by magazines) Frost wrote “Only more sure that all I thought was true.” That is blunt and brusque: the published version is subtle. So much in Frost’s work hangs upon so little, just as his mood can be changed by a simple dusting of snow.

So Frost began his career with a poem about a mid-life crisis, about being lost on the pathless wood, but also with a declaration that the crisis would only make him more sure of himself.

“Into My Own” comes to mind when reading “Stopping by Woods”, his most famous Dantean poem about the “dark and deep” woods, which tempt the speaker as if they are a place where, as he says in “Birches” he can “get away from earth awhile.” Frost stops to watch the woods fill up with snow. Eventually, his horse breaks his reverie.

He gives his harness bells a shake

To ask if there is some mistake

As with the dust of snow, Frost’s temperament requires him to be called back from his imagination, from going too far into his own. The bells summon him out of the temptations of the forest.

When he does go into the woods, Frost’s poetry is about being lost. “The Road Not Taken” is a joke about people who never know which path to take on a walk and never realise that their choice hardly matters—even though they will tell themselves it matters very much. They think there is a path—a road not taken—but in fact both routes “lay/ In leaves no step had trodden black.”

In “Birches” he wrote more seriously about that sense of not knowing which way to turn in the woods.

It’s when I’m weary of considerations,

And life is too much like a pathless wood

Where your face burns and tickles with the cobwebs

Broken across it, and one eye is weeping

From a twig’s having lashed across it open.

I’d like to get away from earth awhile

And then come back to it and begin over.

The pathless wood is Frost’s central concern. He wrote those lines in England, and they describe exactly what he had done. England was his means of getting away from earth awhile when life was too much like a pathless wood: and when he got back to America he did begin over, as the most in-demand poet of the time, with his book selling two-hundred thousand copies, and the editors who had ignored him now rushing to print his work. When Frost was lost in the pathless wood he knew that he was stuck there, that he needed shaking out of it, that he was really sure of what he knew was true.

Frost’s final poem is about this too, but the perspective has changed.

In winter in the woods alone

Against the trees I go.

I mark a maple for my own

And lay the maple low.At four o’clock I shoulder axe

And in the afterglow

I link a line of shadowy tracks

Across the tinted snow.I see for Nature no defeat

In one tree’s overthrow

Or for myself in my retreat

For yet another blow.

At the end of his career, Frost is no longer captured, almost catatonic, with the dream of going into the woods. He no longer needs shaking out of the reveries of the dark forest. The rhyme scheme is linked, like his shadowy tracks, across all three stanzas (go, low, glow, snow, throw, blow). In his other poems, the path was not there to be found. Now he has discovered it: it was not the road less travelled, it was not a path someone else had trodden. They really had been pathless woods. Frost had to make his own tracks. His final published poem is thus a metaphor for his life as an artist. The poet must go into the dark forest and cut down their own tree: there is no well-trodden path for the artist. They first must go into the dark forest, lost on the path, and then they must find their way out.

I see for Nature no defeat

In one tree’s overthrow

Or for myself in my retreat

For yet another blow.

Why is the line "For yet another blow" and not "From yet another blow"?

A great piece. Thank you.