How long until AI writes a great poem?

Will we even care if it does?

In a recent podcast, Tyler Cowen asked Sam Altman how good GPT 6 will be at poetry. Altman turned the question round to Tyler, who said he thinks we’ll have a poem as good as the median Pablo Neruda poem in a year. But “there’s a big gap between a Neruda poem that’s a 7 on a scale of 1 to 10 and one that’s a 10. I’m not sure you’ll ever reach the 10. I think you’ll reach the 8.8 within a few years.”

Altman replied: “I think we will reach the 10, and you won’t care.”

We won’t care?

You’ll care in terms of the technological accomplishment, but in terms of the great pieces of art and emotion and whatever else produced by humanity, you care a lot about the person or that a person produced it. It’s definitely something for an AI to write a 10 on its technical merits.

Altman gave the example of chess. “The greatest chess players don’t really care that AI is hugely better than them at chess. It doesn’t demotivate them to play... Watching two AIs play each other, not that fun for that long.”

But is poetry like chess?

There are various definitions of poetry: they rely on mood, strong feeling, perhaps some sort of personal expression, as well as the use of language in novel and illuminating ways.1 We can quibble the definitions all day: something about poetry makes it incomparable to chess, or least makes it an imperfect comparison. We value art because it is beautiful, meaningful, strange, and disarming, as well as for its structures, patterns, forms, and formulas. I don’t share Altman’s optimism that we won’t care if GPT writes a truly great poem: we are running an experiment and we are going to find out whether poems have to be human-made to be appreciated by humans…

COWEN: Let me tell you my worry about reaching the 10. Evaluations rely a lot on these rubrics. The rubrics will become good enough to produce very good poems, but maybe there’s something about the 10 poem that stands outside the rubric. If you’re just training on rubrics, rubrics, rubrics, it might in a way be counterproductive for reaching the 10.

ALTMAN: Evals can rely on a lot of things, including when you call upon the 10 and when you don’t. You can read a bunch in the process and provide some real-time signal.

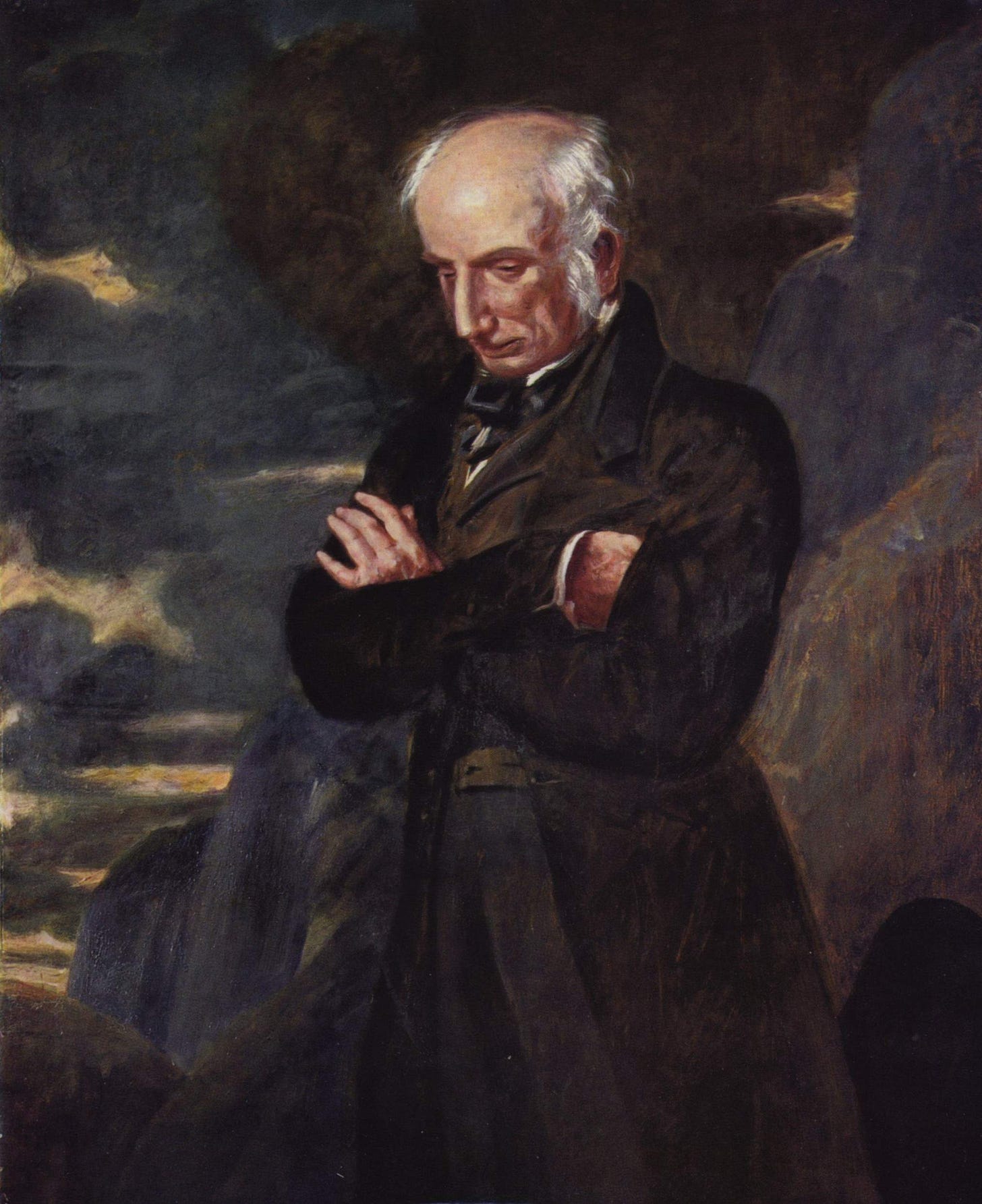

COWEN: Say we have no human poets today writing 10s, and we’re asking those same people to judge and grade the GPTs. I’m worried. Again, I think it will be fine. To me, we’re talking about a 9, not a 10. You don’t have William Wordsworth working for OpenAI.

ALTMAN: This gets to a very interesting thing, which is, let’s say you can’t write a 10, but you can decide when something is a 10. That might be all that we need.

COWEN: Maybe humanity only decides collectively what’s a 10, and there’s something a little mysterious and history-laden about that process.

ALTMAN: … whatever process humanity has to determine what poem is a 10, you could imagine that providing some sort of signal to an AI. Now that, again, if you know it’s an AI, maybe you don’t care. We see this phenomenon with AI art…

There are three ways in which we decide what art is excellent.

First, tradition. Strong poets memorialize each other. Like ecologies, the history of poetry is a history of webs and chains of influence and inheritance and variation and deviation.

Second, criticism. Critics and scholars read widely and with specialisation and use their knowledge to compare and contrast works of literature, so that we can know “how they are what they are”. (This is not Arnold’s awful touchstone theory, but something more akin to Smith’s approach in Lectures on Rhetoric.)

Finally, Johnson’s common reader. Literature is judged by all of its readers, not just its professional ones.

None of this means authors are only known to be great after they are dead. That wasn’t true of Wordsworth, nor many others. But it does mean, as Tyler says, that we decide collectively and we don’t quite know how we decide.

Altman’s “eval” approach only involves two of the three ways we have of canonising poetry—critical response and audience response, and it seems unlikely that many of the right scholars or critics are working for AI companies. If they are, then I get more pessimistic: the poetry currently being produced by LLMs isn’t good enough.

What remains most likely, in my view, is that the AIs will be best at writing poetry for each other. Then the question becomes, what will the human poets learn from the AI ones…

Some that come to mind: emotion recollected in tranquility; an escape from emotion and personality; eloquence is heard, poetry is overheard; almost a remembrance; excellence in language and the expression of a great spirit; what oft was thought but ne’er so well expressed; the beautiful bizarre.

I do appreciate you keeping track of what the Large Language Model billionaire tech oligarchs think about their plagiarism literatures. I just seriously doubt they've actually read any poetry, like, ever.

I feel like there's something missing in this notion of a "10" poem, as if what made a poem great was the feeling of 10ness it induced in us, and there is some fixed set of features we can identify that evoke that feeling of 10ness. But I don't think that's right? At least not about writing in general.

Great writing is part of a conversation about what is interesting, or important, or beautiful, about the world around us. It comes from having something you want to say about the world to the people around you. That's not what LLMs are for, at the moment. Right now, do not want to say anything new and interesting and provocative; mostly, they want to cautiously aggregate and apply the current expert consensus.