Late Bloomer GPT

If you can’t wait to read my book about late bloomers, try the GPT now live. Ask it anything about being a late bloomer, and it gives you answers based on my book.

The question of good taste is once again in vogue. Before Christmas, Dirt ran a series about ‘The Future of Writing’, in which Monika Woods wrote about the mediocrity of modern writing.

Subjectivity rules us all— the subjectivity of people who have bad taste.

Woods quotes Merve Emre that too many writers have nothing to say and no good way of saying it.

Tomiwa Owolade wrote in the Times this week about this philistine supremacy in modern culture, where so many adults are Harry Potter fans and read YA fiction. He quotes A.S. Byatt’s comment that adult fans of Harry Potter lack a sense of the mystery of life. Then says,

Yet confronting human nature, in all its wildness and variety, is crucial for any work of art. As Harold Bloom, the American literary critic and author of The Western Canon, once put it: “We read [the great works] to find ourselves, more fully and more strangely than otherwise we could hope to find.”

But good taste must have something to do with subjectivity. Good taste must be related to what we enjoy.

In a recent interview with Ezra Klein, Kyle Chayka, the New Yorker writer with a new book about the internet and taste coming out, defines taste like this:

taste is knowing who you are and knowing what you like, and then being able to look outside of yourself, see the world around you, and then pick out the one thing from around you that does resonate with you, that makes you feel like you are who you are or that you can incorporate into your mindset and worldview.

Chayka notes that taste is not about superficial consumption of whatever you happen enjoy, “but instead almost making it part of yourself.” Ezra Klein responded to this by saying,

I thought I could have good taste or bad taste, and I mostly thought I had bad taste… it’s relatively recent for me that I began to realize the first question is, what do I actually like and why?

The insight to take away from this (though it isn’t novel, and I’m surprised people need to hear it) is to follow your gut, find what speaks to you. A man must study that which he most affects, said Shakespeare. A man ought to read just as inclination leads him, said Johnson. For autodidacts like Virginia Woolf, this was the only way to read. Her work is saturated with this principle.

Klein is reacting to the snobbery of good taste, which leads people to pretend to enjoy art for social reasons. Talking about good taste and bad taste often invokes such snobbery, as if bad people have bad taste. This isn’t true, of course. Reading Jilly Cooper or Colleen Hoover or Prince Harry doesn’t mean that you are bad. But no-one sensible can equate those books with the work of George Eliot. No-one who has read a lot of literature and, as Chayka says, made it part of themselves, would equate them.

The way we can relate personal taste and good taste is realising that taste is knowledge, as Chayka and Klein intimate but don’t say. Having good taste in wine means being able to identify what you are drinking, being able to distinguish various grapes and regions; similarly, having good taste in art means knowing what you are reading, watching, or hearing.

The better we know a piece of art, the more we can see it for it is, and not have our judgement clouded by our pre-existing feelings. The more we have read, the better we know where a new book fits. The more ignorant we are, the more likely it is that we will be dazzled by mediocrity. Charms strike the sight, but merit wins the soul, as Alexander Pope said.1 Good taste is accumulated through wide knowledge.

Believing that taste is a primarily personal question means believing that the canon is the canon because lots of people happen to prefer reading revenge tragedies and epic poems about Satan to reading anything else. It means believing that Chaucer is canonical because, much in the way some people prefer reading murder mysteries, many others prefer medieval stories told in iambic pentameter. Writers like Dante and Homer are not canonical because of a wide-spread personal taste for stories about the afterlife told in terza rima or because of a universal penchant for adventure stories with monsters told in hexameters. This is obviously false. The canon has been reapproved every generation because it is full of strange, unique, inventive, insightful work. It challenges us and shows us bigger things in life.

Klein gives the example of trying to appreciate classical music, and struggling to find a way in until he heard Steve Reich and Philip Glass and others. They spoke to him in a way other composers didn’t. But that was about picking between two sorts of excellence. Klein was choosing between varieties of the good. He was comparing classical composers, not picking between J.S. Bach and Taylor Swift. Eventually, I wager, after hearing enough modern minimalism, Klein will find his way into earlier music. One sure way to appreciate the canon is to trace the chain of influences backwards.

But look at the role of aspiration here. If Klein hadn’t started out wanting to appreciate classical music, listening to a lot that didn’t speak to him, he wouldn’t have expanded his taste. He didn’t only listen to his gut, he listened to his inner wish to find something better. And he spent ten months listening before he found this work. His knowledge base expanded. Taste is more than preference.

When we prioritise our own reaction to art, we assume that those reactions are about the art. But if you are misreading a piece of writing, without knowing it, your feelings will be more to do with you than with the writing, and thus not a response to the writing at all. When we misunderstand what we read, our feelings make us pay more attention to what is familiar in the writing than to what is unfamiliar. Thus believing that taste is primarily personal encourages us to not react to the writing, but instead repeat what we already think and feel. And so bad taste perpetuates itself.

Once we aspire, like Klein, to appreciate the best work, we begin to pay attention, acquire knowledge, and to see our personal reactions and deep feelings as only one important way of assessing great work. The more we can find in these great works of art, the broader the range of responses we can have. Struggling through works that are beyond us leads to new levels of understanding, new depths of feeling.

The more you sample, the better and broader your taste will be. The more you stick to what already speaks to you, the more limited and narrow your taste. Call it good taste or don’t, it’s all the same.

The current revolt against philistinism is rooted in the idea that we are taking the easy path. Woods writes about people who churn out unchallenging essays. Owolade argues against the easy passive watching of superhero franchise movies and the childish enjoyment of Harry Potter among adults. Chayka and Klein agreed that it is easier now to be a passive consumer, and the generic consumption of bland culture is what capitalism prefers. Hence people struggle to break out of the Harry Potter doom loop.

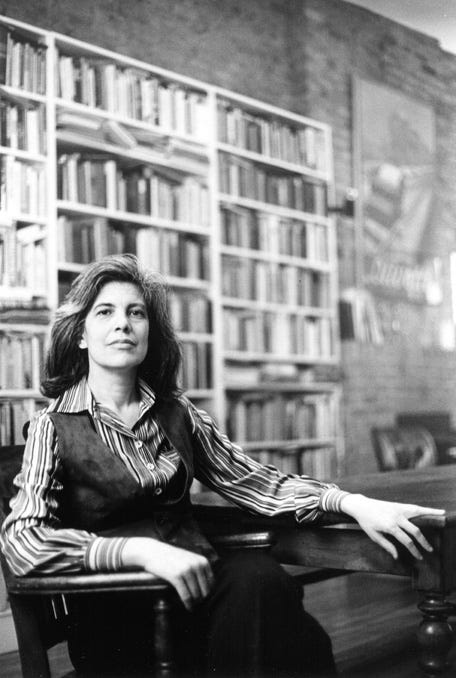

I disagree that capitalism and the internet make it harder to have good taste. The resistance of philistinism is as old as the ages. Before Harold Bloom, Susan Sontag was fighting the good fight. Before her, the Modernists and Victorians with their periodicals. Before them, Samuel Johnson said the aim of criticism was to improve opinion into knowledge. The Romans satirised philistines. And on, and on.

Listening to yourself is the starting point. But if you dislike canonical books, it is less likely that the books that you believe to be inferior are a fraud on the public than that you are mistaken. Have you really read enough to know? You must read the works that challenge and defeat you, or try. You must see what they are, even if you do not admire them. As Susan Sontag said, to understand art we shouldn’t focus on the content (whether that’s political art that tells us what we want to hear, or easy art that appeals to our genre preferences). Instead, we must be able to say how it is what it is. We must have read, seen, and heard enough to know how each new work compares, where it fits.

Listening to yourself is the route to good taste, but so is listening to other people. We catch the fire of other people’s enthusiasm, which is rooted in their knowledge. That is how we discover newer, better things, be they novels, films, symphonies, cuisines, clothes. It has never been easier to find out what are the greatest works of art ever made. It has never been easier or cheaper to read, watch, or hear them.

Some people don’t want good taste. Fine. Leave them be. There was never an easy way to have good taste. But today if you want to experience the heights of human accomplishment, you can. And much more easily than before.

The only thing stopping you, is you.

I had this as Johnson originally, whoops!, but have corrected it.

Taste is knowledge, sure. But it’s also power. And when you come from a place like Afghanistan, you learn pretty quickly that what the world considers “good taste” is really just what it has decided to pay attention to.

I read this and couldn’t help but think—if taste is about depth, about challenging yourself, then why is so much of the world’s literary diet so shallow? Why do people who consider themselves well-read know The Iliad but not Shahnama? Why do they dissect T.S. Eliot but have never heard of Rumi beyond an Instagram quote? Why does “good taste” always seem to align with Western traditions, while everything else is an “acquired taste”?

Afghanistan has produced poetry for over a thousand years, but you’d be hard-pressed to find it on a university syllabus outside the region. Our architecture, our art, our music—so much of it dismissed, reduced to the backdrop of war. Even when the world looks at Afghanistan, it sees rubble, not the ruins of civilisations that once shaped entire empires.

Maybe good taste isn’t just about refinement or expertise—it’s about curiosity. It’s about looking past what’s been handed to you and wondering what got left out. Because if taste is really about knowledge, then the greatest ignorance of all is assuming you already know enough.

Good taste is accumulated through wide knowledge, but that knowledge can only be acquired through one crucial trait - i.e. curiosity. Which is what drove Klein to attempting to investigate classical music, and which is a trait I'd wager many of those who are 'content with mediocrity' (including, sometimes, myself) usually lack.

Even taking the example of Harry Potter - there are those who read it and then feel compelled to seek out information about the works and people cited as J.K. Rowling's influences and favourites, from Jessica Mitford to E. Nesbit to Jane Austen (I had a friend whose interest in Latin American magical realist literature was triggered, indirectly, through the Harry Potter films films - she loved Alfonso Cuaron's one so much that she made her way through his entire filmography and then sought out 'books with the same feel' - she was 19 at the time). I've had friends who read Asterix as small children and then, as adults, proceeded to investigate - even if it was through a mere wikipedia search in some cases - every work of art and literature referenced in the comics (the same friend mentioned above read Shakespeare's Julius Caesar because said Julius frequently turns up in Asterix - she didn't like it, but mentioned to me that she enjoyed it more than she'd thought she would because she pictured Julius in the play the way he was drawn in the comics).

The 'Harry Potter adults' who only read YA fiction, are operating in the opposite direction - they aren't seeking a greater understanding of the forces that created the thing they like, they just want 'something like it'. Something the algorithm understands very well, with the 'if you liked this, you'll like that' genre of recommendations proving so popular.