This Sunday we are discussing A Midsummer Night’s Dream at 19.00 UK time. Here is the full Shakespeare schedule.

Plague

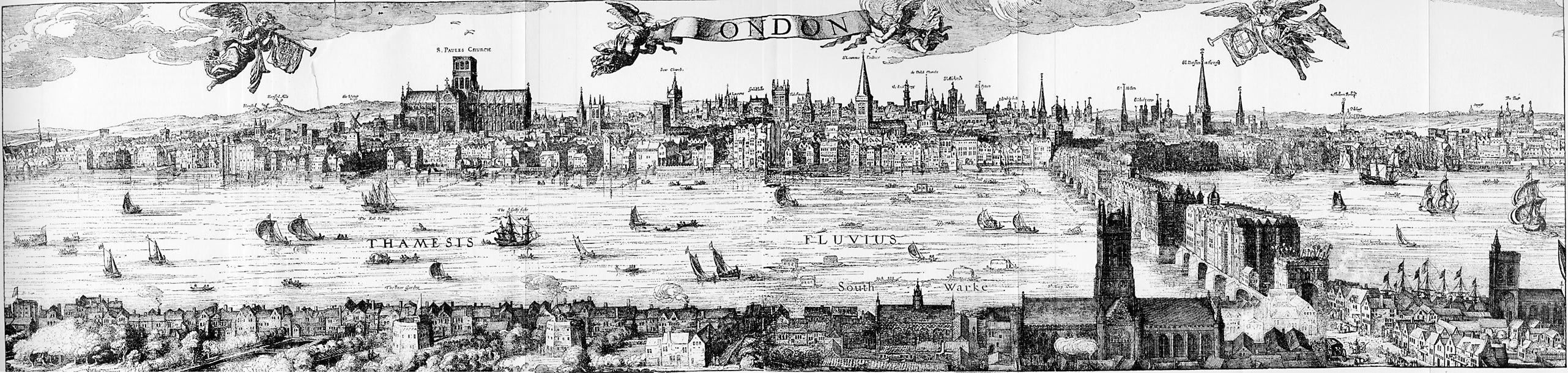

In 1592, the plague arrived in London. This was the last great plague of the century, but it hit hard. London lost 8% of its population, with some twenty thousand dead. Shakespeare was a young playwright and actor at this time. Now the theatres were closed for two years.

When they opened again in 1594, Shakespeare began an extraordinary period of creativity. Between 1594 and 1597, he wrote Comedy of Errors, Love’s Labour’s Lost, Romeo and Juliet, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, King John, Richard II. This is the second phase of his career. It is a highly lyrical phase, full of intricate rhetoric and vivid poetry. The Comedy of Errors is a lovely play, but Richard II is a jewel in the Shakespearean crown. In this brief period, Shakespeare wrote several of his most sparkling, most loved plays. He wrote in three years thousands of lines that are still performed, memorised, and anthologised.

This is the first tipping point of his career. Several times, Shakespeare’s innovations come flaring out, as he competes with other writers and adjusts to the tastes of the times.

Before the plague, in his early apprentice phase, Shakespeare developed his history plays in Henry VI and Richard III and wrote the early comedies Taming of the Shrew and Two Gentlemen of Verona. After the plague, he was writing masterpieces that show huge development in dramaturgy and lyricism.

Two developments contributed to this leap forward: a new theatre company and the poetic culture of the 1590s.

Lord Chamberlain

In May 1594, Henry Carey, first Baron Hunsdon and lord chamberlain of the queen's household set up the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. His job was to provide the Queen with the best entertainment during Christmas. The idea was that plays would be written and performed in the theatres in the suburbs of the City, and the best would be performed for Good Queen Bess. The City of London was usually hostile to players, believing they practised and encouraged immorality, which is why they required special licensing. Shakespeare joined this new group. It was, from the start, a new way of working. Andrew Gurr writes, in The Oxford Dictionary of Biography.

The new acting companies of the 1590s at first provided a notable exception to the prevailing rule among Elizabethan organizations, which were normally decidedly autocratic in character, being ruled either by a citizen paterfamilias or by a lord with inherited authority. By contrast, each company worked as a team, sharing the members' assets, income, and costs.

Being part of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men meant Shakespeare had permanent colleagues. Actors like Burbage (tragic hero) and Armin (clown) worked with him on every play, and allowed him to develop and experiment his parts in accordance with their specific talents.

Poetic culture

In the two year period of theatre closures, as well as touring the provinces, Shakespeare had written poetry. Venus and Adonis is, as Peter Holland says in the ODNB, a mixture of the comic and erotic, a combination that became a hallmark of Shakespeare’s writing. It was one of his most popular works, running to fifteen editions by 1636. That is more than any of his other printed works.

The 1590s was a great decade for poetry. Elizabethan England had a flourishing of verse. Spenser’s Faerie Queene and Sidney’s Arcadia and Astrophel and Stella were published. Writers like Thomas Campion, Samuel Daniel, Michael Drayton, and Walter Raleigh were all publishing. Anthologies like The Phoenix Nest and translations like Chapman’s Homer came out. There were sonnets, epics, epithalamions, ottava rima, pastorals, allegories, satires, lyrics…

This was a rich tradition for several reasons. English was in a state of immense growth. Thousands of words were being added as the language grew to accommodate all the new ideas being translated from the Latin. There was a strong poetic tradition from earlier in the century (Wyatt, Surrey, Howard). And many splendid lyrics were written for, or influenced by, lute songs and madrigals. Campion is the great poet of the sung lyric and his words read beautifully today.

So Shakespeare is the pinnacle of a teeming culture. The theatres flourished in a culture that was expanding in all sorts of ways. London was full of the effects of trade, travel, and translation. The population was growing. The beneficial effects of selling the monasteries into private hands a generation earlier were an economic boon (it enabled the building of the theatres for one thing). And there was a glut of grammar-school educated young men, who wanted their entertainment to be both bawdy and witty, a combination at which Shakespeare excelled.

The effects are obvious everywhere: mellifluous lines of verse, sonnets embedded into plays, a merry excess of puns and rhetorical tropes. Shakespeare was taking so much that existed in the poetic and dramatic culture of his time and condensing into half a dozen plays, mocking it, replicating it, bettering it. After the dullness of the Henry VI plays, and the unevenness of Richard III, we suddenly get the startling feeling of his immense productivity.

With the new comedies, and Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeare’s genius has met the conditions of his time and a new brilliance emerged.

Relevant reading

You can find more details about Shakespeare responding to his contemporaries in my notes about Love’s Labour’s Lost.

Here are my notes about Romeo and Juliet, which has some basic information about the original Theatre, and a little more about contemporary influence. (I also wrote about Romeo and Juliet.)

And here are last month’s notes about Comedy of Errors.

I am fairly unread in Shakespeare. I was exposed to his work many years ago at school - The Merchant of Venice and King Lear - and was not particularly appreciative of it at the time. I have attended occasional plays and have seen some films. I've been reading your posts with interest as I would like to become more knowledgeable and to experience the pleasures of Shakespeare. I'm curious to know why you described Richard II as the jewel in the Shakespearean crown. Over the years I've been aware of the various Shakespeare plays and films that are about, but I can't remember much ever being made about Richard II. I must add that I live in New Zealand so the scope for exposure to a range of Shakespeare is more limited than in the UK.

s

do you think it's feasible Shakespeare ever worked as a translator? (of Latin I'm guessing, not clear to me if it was likely he ever spoke, say, French too or something)