The three parts of Henry VI, Shakespeare’s early history trilogy, are just as boring and obtuse as their reputation claims. They conform to the Shakespeare of stereotype: full of long speeches that rant and rave and could easily be cut down. Like all mediocre drama, they run on exposition. I can hardly bear to read them, they are so dull. These plays are not kingdoms but boredoms.

There are many soliloquies and speeches, such as those given to Richard of York, and they have none of the defining Shakespearean quality of self-overhearing. They rant and rave and spell out the day. They proclaim and narrate and lament. But never once do they catch themselves in the act of thinking. Never once do they become recursive, starting that endless, ineffable tumbling into self-awareness that constitutes individualism.

In The Third Part, York gives a speech on the battlefield. He is alone on the stage. He knows that death is stalking him. The battle has run against his luck. These are the sorts of speeches that later become one of the jewels in Shakespeare’s crown. Think of Richard II at Pontefract or Othello at the bedside. But there is no sign of the later genius here.

The army of the queen hath got the field:

My uncles both are slain in rescuing me;

And all my followers to the eager foe

Turn back and fly, like ships before the wind

Or lambs pursued by hunger-starved wolves.

My sons, God knows what hath bechanced them:

But this I know, they have demean’d themselves

Like men born to renown by life or death.

The metaphors are ordinary, the tale is all like that of a chorus, and the feelings are plain. (demean’d means behaved; think of the modern word demeanour).1

Three times did Richard make a lane to me.

And thrice cried “Courage, father! fight it out!”

And full as oft came Edward to my side,

With purple falchion, painted to the hilt

In blood of those that had encounter’d him:

And when the hardiest warriors did retire,

Richard cried “Charge! and give no foot of ground!”

And cried “A crown, or else a glorious tomb!

A sceptre, or an earthly sepulchre!”

With this, we charged again: but, out, alas!

We bodged again; as I have seen a swan

With bootless labour swim against the tide

And spend her strength with over-matching waves.

There is something in the metaphor of the swan, but whatever elegance it achieves is inappropriate to the scene. Death is closing in, closer and closer every line. The pattern is simple and bold. The insistence is wearying. And yet, all York can express are outward things.

A short alarum within

Ah, hark! the fatal followers do pursue;

And I am faint and cannot fly their fury:

And were I strong, I would not shun their fury:

The sands are number’d that make up my life;

Here must I stay, and here my life must end.

Even at the end we have no more than tropes and templates. He could be anyone, a stock figure of noble fright upon a furious stage. Just think what the Shakespeare of a decade later could have done with this! Just think how memorable it could have been! We have no hints here of what he will become.

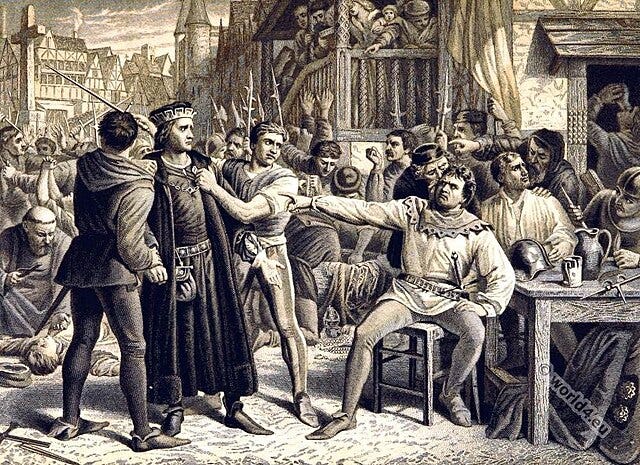

This is why Jack Cade’s scenes in The Second Part of Henry VI are so often remembered: because they contain an early hint of the essence of Shakespeare’s dramaturgy: the mingling of the serious and the comic. The rebellion scene arrives upon the beleaguered reader with the refreshing sensation of a window being opened in a room for the first time in several weeks.

CADE: We, John Cade, so termed of our supposed father—

DICK: ⌜aside⌝ Or rather of stealing a cade of herrings.

CADE: For our enemies shall fall before us, inspired with the spirit of putting down kings and princes—command silence.

DICK: Silence!CADE: My father was a Mortimer—

DICK: ⌜aside⌝ He was an honest man and a good bricklayer.

CADE: My mother a Plantagenet—

DICK: ⌜aside⌝ I knew her well; she was a midwife.

CAD: My wife descended of the Lacys.

DICK: ⌜aside⌝ She was indeed a peddler’s daughter, and sold many laces.

These asides are full of vibrancy, with the quality of humour we still see today in stand-up comedy. There is a lineage to Don Rickles and Ricky Gervais in this bantering, abusive, everyman humour. Shakespeare may not be sympathetic to the mob—the whole tenor of these plays, as with his other work, is indignant fear of the populist fire—but he can parse their humour in the fullness of its life. What later made him popular among theatregoers and hated among the intellectuals like Voltaire was this combination of terror and humour: the porter in Macbeth, Hamlet joking with the gravediggers, even in Coriolanus which is monologically distraught, the scene with the waiters dreaming lustily of the stirring world, intermingles the coarseness of everyday life with the grandeur of high tragedy. In his combined hatred of mass politics but keen appreciative ear for mass speech Shakespeare discovered in these scenes one of the core concerns of his art: what Johnson called the “chaos of mingled purposes and casualties”. It is in these scenes that Shakespeare creates more catching images, too, such as that of the beeswax.

CADE: Be brave, then, for your captain is brave and vows reformation. There shall be in England seven halfpenny loaves sold for a penny. The three-hooped pot shall have ten hoops, and I will make it felony to drink small beer. All the realm shall be in common, and in Cheapside shall my palfrey go to grass. And when I am king, as king I will be—

ALL: God save your Majesty!

CADE: I thank you, good people.—There shall be no money; all shall eat and drink on my score; and I will apparel them all in one livery, that they may agree like brothers and worship me their lord.

DICK: The first thing we do, let’s kill all the lawyers.

CADE: Nay, that I mean to do. Is not this a lamentable thing, that of the skin of an innocent lamb should be made parchment? That parchment, being scribbled o’er, should undo a man? Some say the bee stings, but I say, ’tis the beeswax; for I did but seal once to a thing, and I was never mine own man since.

It would not be until Richard III that Shakespeare began to discover how to dramatise the interiority of a character over-hearing themselves. In the Henry VI trilogy, the heroes are stock figures. But in Cade’s rebellion he discovered how to show the stirring world as a mingled one, where comedy and tragedy combine buddingly together. It was this discovery that set him on the course to the flowering of the late 1590s and the great tragedies that followed.

https://www.etymonline.com/word/demeanour#etymonline_v_25955

Maybe not reaching the heights and insights of Hamlet, Lear et al but boredom? I recently watched the Peter Hall Wars of the Roses adaptation for the first time and was really impressed. I'll have to look at the text for examples...but I did like the way the two French women, Joan of Arc and Margaret of Anjou are front and centre. Whereas Richard III? Alway entertaining but a bit of a pantomine... looking forward to your bookclub.

enjoyed the BBC Hollow Crown adaptations of the Henry VI plays, but stunned by how Jack Cade and his rebellion were completely absent from the story.

also thoroughly enjoyed Nuttall in The Thinker on this, taking up this initial idea in Shakespeare's earlier plays of a twinned nature that's more socially concerned, and later showing how it's then compressed and internalised in Richard III - just a marvellous observation, and as you suggest the beginning of something great. looking forward to book club