The messy theory of history

Welcome to the Age of Mess

Housekeeping

There has been a suggestion for a meet-up in London to discuss Mill’s Autobiography. Let me know if you are interested.

The next bookclub is on 26th November, 19.00 UK time. We are reading Darwin. Selected Letters and The Origin of Species. For letters, any edition will do, and it’s less essential than Origin.

On November 9th, I am running my final salon in the ‘How to Read a Poem’ series.

In case you missed it—some recent articles on the Common Reader

What if there is no explanation for what’s going on?

What could explain the evidence of the current UK Covid Inquiry better than to say that the whole thing was a muddle? When you see that many Trump and Biden policies are more similar than their rhetoric, does it make sense to say that a nation is at a crossroads with only two clear options? What if Liz Truss had come in a few weeks later, when energy futures were dropping—would she still be prime minister?

These three questions show us that history may often be morally simple—Johnson screwed up, Trump is bad, Truss was wrong—but the stories we tell rarely fit all of the data. We talk about living through an era of neoliberalism, wokeism, or any other ism. But it’s never so clear cut. There’s too much going on. Things happen and we retrofit a narrative. We believe our stories, and we forgot that life doesn’t have to make sense. Politics and history are long tales of contradiction. Sometimes, there isn’t an explanation so much as a muddle.

In Genius Creativity & Leadership Dean Keith Simonton reports data gathered by Pitirm Sorokin about the balance of different ideas—materialism and non-materialism—throughout history. The finding was that there is rarely, if ever, a pure zeitgeist.

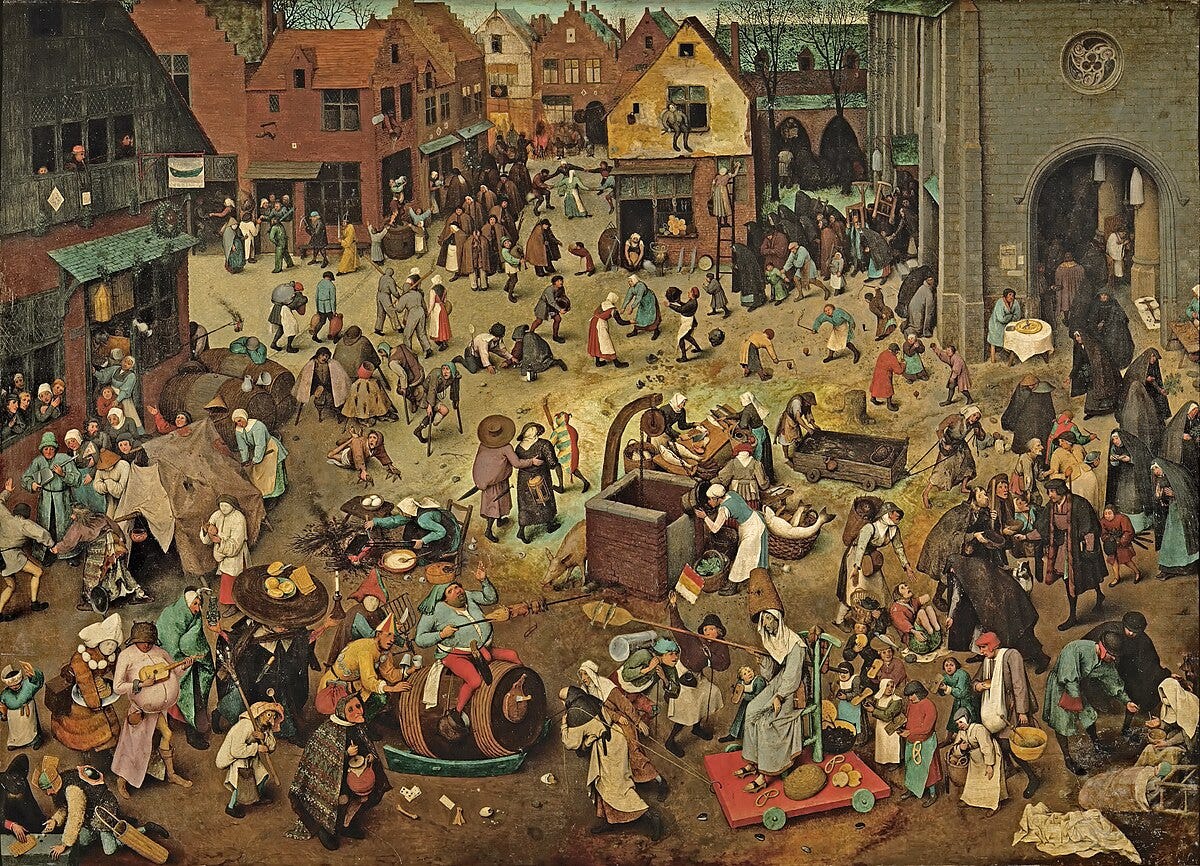

All ages are a mix of ideas, more of a mess than a pattern. Data like this is hardly to be taken at face value, but the more you know about any period the more you will see it as a messy mix than an Age of Anything. Think about the Enlightenment—that was also the time of the Clapham Sect, the evangelicals who ended the slave trade. Read Moral Capital and you’ll see that during the Age of Reason it was religious ideas that successfully campaigned for abolition.

This sort of messiness is everywhere in history. The sociologist Rodney Stark showed that the idea of a religious decline in the twentieth century was overstated. Historians used to call the thirteenth century the Age of Faith, but Stark showed that people used to lie in bed and skip the sermon then as now. The new consensus, Stark said, was that “lack of religious participation was, if anything, even more widespread in medieval times than now.” (He was writing in 1999.) At the time when the church was most dominant, it was quite possibly also least dominant.

Again and again in history, you can find a messy theory that takes account of more information, and will trump the narrative you thought was predominant.

The story of the civil war is that Charles I and Parliament were ideological antagonists whose conflict built up to unavoidable war. But J.P. Kenyon demonstrated that there were long periods where nothing much happened between Charles and Parliament. War didn’t seem a very likely possibility, until events changed. There were hinge moments, and some of them went wrong.

The story of the corn laws is that Peel split his party after a campaign by Cobden and Bright, in order to feed the poor. K. Theodore Hoppen writes that the split wasn’t so great, several Peelites changed sides again afterwards, and that Cobden and Bright said a lot, but didn’t make much difference in the final reckoning. And the decades that followed, though dominated by Liberal governments, were not especially liberal. Many of the measures of Gladstone’s famous first budget were gradually whittled away by the pressures of circumstance.

We can go on and on. There was a failed abolition movement before Wilberforce. The suffragettes were far from the first in their cause, and were perhaps the least helpful. Churchill was a racist as well as a hero of democracy. Truman is credited with dropping the bomb; but we are unable to say “the decision was made on this day”. The 2008 financial crisis wasn’t caused by a housing crisis, but was largely the result of panic—a failure to interpret events for what they were, a failure to see a mess rather than a narrative.

Historians debate whether history is made by individuals, or the vast impersonal forces of society, or economic materialism, or ideas. The only theory that makes any sense is that history is messy. Different theories are needed, in combination, to make sense of different periods.

We shouldn’t let the fact that most history is messy distract us from moral imperatives, but it is important to conceptualise history correctly because it affects how we understand politics. When you read the news, you often feel this sense of messiness. But the more strongly we hold beliefs about “what history is”, or about any particular narrative, the harder it is to see the events in front of us for what they are—a mess.

Will there be a way to access the How To Read A Poem series if we weren't able to make the salons? Interintellect has a podcast feed, but it looks like they posts some of the salons.

History is a mess until we're met with one great clarifying force, which is war. Or any form of organized and sustained large scale violence such as the Rwandan genocide. So, in that way. mess is good!