Ely Cathedral and the beauty of progress.

And a note about paid subscriptions.

Before we get started on Ely Cathedral, a note about reaching one year of paid subscriptions.

This month marks one year of paid subscriptions on The Common Reader. I never imagined there would be hundreds of you!

When people subscribe they often leave a note. Some say they had to finish the piece about J.S. Mill and the death penalty or they’d go mad. Others talk about how they got soured on literature in grad school and are pleased to find writing filled with the passion that made them love books to begin with. One of my favourite comments was that The Common Reader is the opposite of facetious.

Mostly what I aim to do is provoke you. Not with brash, attention-seeking provocation, but in the Emerson manner, who said,

Truly speaking, it is not instruction, but provocation, that I can receive from another soul. What he announces, I must find true in me, or reject.

To cut to the chase, if you enjoy my provocations, I’d like you to consider becoming a paid subscriber.

My recent essay for paid-subscribers ‘How to Have Good Taste’ was briefly un-paywalled and became one of the more popular things I’ve written recently. Cultivating taste is what The Common Reader is all about. Not just personal “I know what I like” taste; but taste as knowledge; taste that isn’t merely subjective, or easy.

Real taste is knowing what you are reading, the way a sommelier knows what grape a wine comes from or a chef can pick out the best ingredients. Taste is the ability to distinguish things based on knowledge. And taste is cultivated through provocation.

In the last year, paid subscribers have read nineteenth century literature and learned “How to Read Literature” more closely and critically. This year we’re reading Shakespeare, continuing with “How to Read Literature”, and I’ll be doing more non-fiction reviews, like this one about David Brooks’ new book. I also plan to write more about modern fiction. And I’ll continue with pieces about talent, like ‘How Mozart became Mozart’. (In fact, I’m currently a little obsessed with Mozart.)

If you want to cultivate your taste, consider becoming a paid subscriber today. It’s approximately the cost of a cup of coffee once a week, but it gives you access to all my writing. And you can join our book club sessions (usually 7pm, UK time, on a Sunday; I’m open to other times.)

Let me provoke you.

Whether you pay or not, it’s a privilege to have an audience, and you’ll always get a free weekly post, as you always have. If I could write entirely for free, I would.

But as 2024 goes on, I’ll continue to put more behind the paywall, as I have been doing recently. It takes time to produce The Common Reader and paid subscribers are helping to make it possible.

Whatever type of subscriber you are, thank you for reading, sharing, commenting, liking the posts, and for emailing me about the books you enjoy. The more you do that, the more The Common Reader grows. It doubled last year thanks to you all.

I also hear from so many of you who have been inspired to try Dickens, Mill, Darwin, or Shakespeare as a result of reading The Common Reader. Those are the best results of my writing.

Progress and architecture

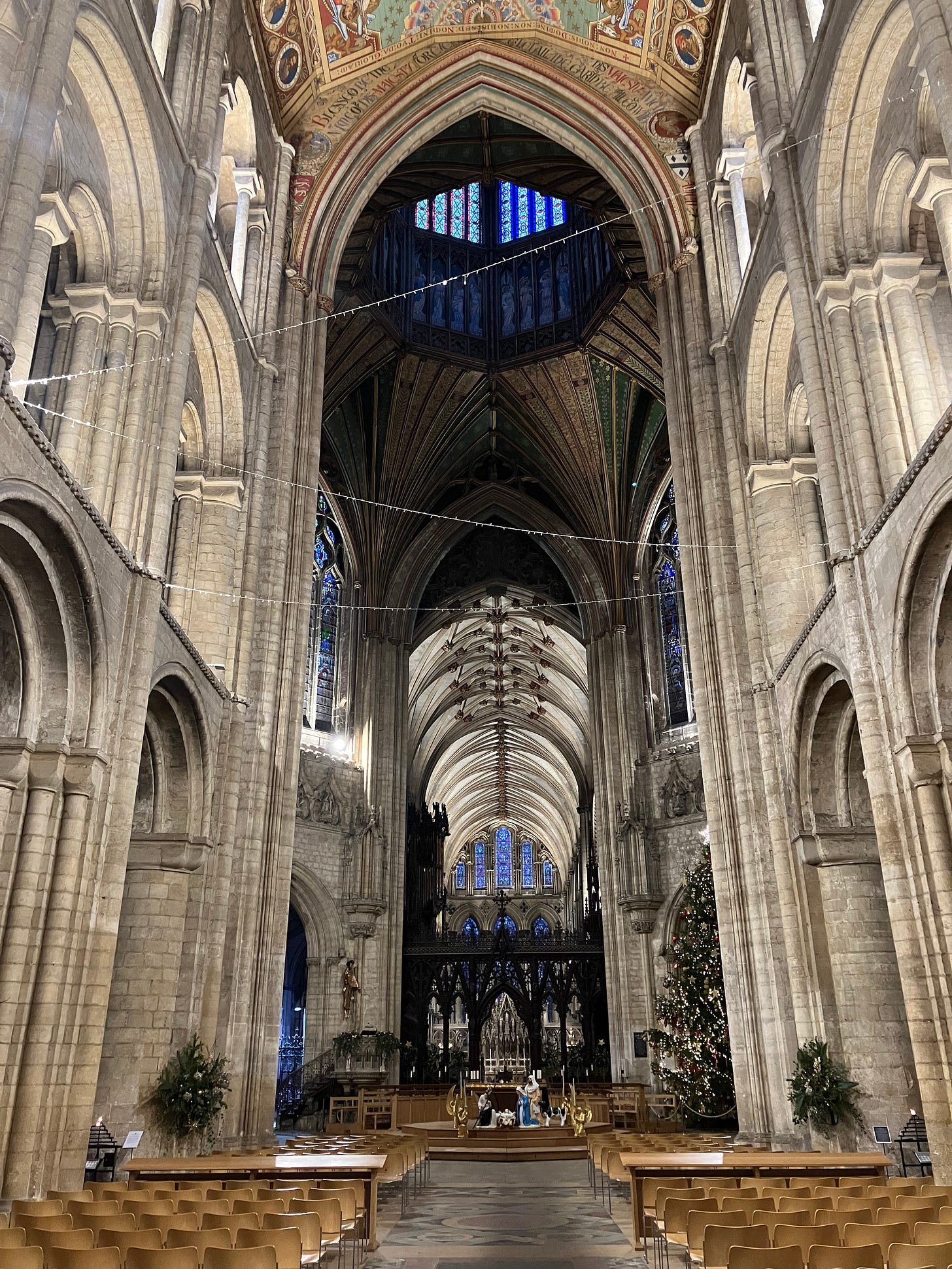

Over Christmas, I visited Ely Cathedral. The nave is Romanesque, built in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. It has thick pillars, and short, rounded arches. Unable to support great weights, these arches have to be repeated on three stories to hold up the nave. It is bulky style of architecture that, while impressive and capable of producing a fine cathedral, lacks grandeur and beauty. I was wondering why Ely was held in such high regard as I wandered along.

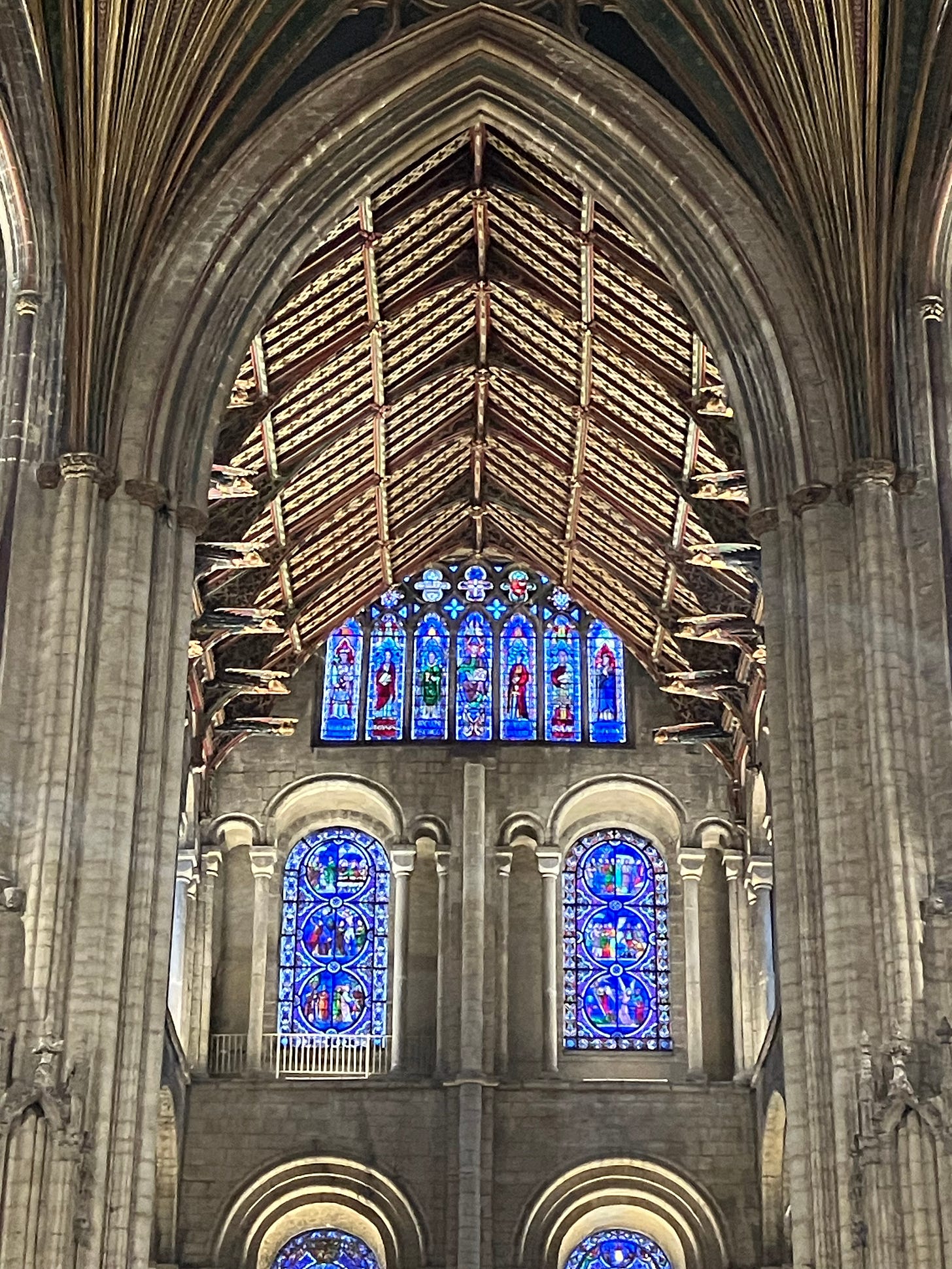

Then, at the end of the nave, the architecture jumps forwards two hundred years, thanks to a rebuild necessitated by the collapse of the old tower. Suddenly, thirteenth and fourteenth century Gothic arches appear, tall and pointed. Romanesque arches bear their weight down directly onto the walls, necessitating thick supporting pillars. The pointed Gothic arches, though, enable thin stone ribs of the arches to criss-cross over the roof and disperse the weight outwards first, allowing for taller, thinner pillars. Hence the forest like aspect of many of the great Gothic cathedrals. Add in flying buttresses outside and amazing new things become possible.

In the middle of Ely Cathedral, you can see all of this intersecting. The transepts have Romanesque walls juxtaposed to Decorated Gothic ceilings, and the tower between them rises high on pointed arches. In the Lady Chapel, you see the beauty of pure Gothic, capable of so much more delicacy. The Lady Chapel is full of elaborate decoration and wonderful nodding ogees, slightly marred by the discordant, unattractive modern altar and Virgin. Pointed arches and rib vaults make larger windows possible too, as you no longer needed so much heavy wall space to support the roof. It is, like the Chapter House at Westminster, one of those rooms that feels set apart from the rest, a truly quiet place.

Walking through Ely Cathedral is like walking through time. You can see, very literally, the way that huge artistic progress is enabled by engineering improvements. With the more effective supporting of pointed arches, Gothic architecture flourished as one of the high points of Western architecture.

Great way to learn about the transition in architecture. For me, the pictures were essential to my understanding.

I'm lucky enough to live in Ely, we're so lucky. Looking forward to talking about Shakespeare on Sunday, I'm finding it amusing using Google Bard to understand the great man's works.