High performers are late bloomers

A large new study in Science

A large new study published in Science has found that the people of the highest accomplishment across chess, sports, science, and music are often not the ones who were the highest performing young people. This is a fascinating new validation of the idea that many top performers are late bloomers.

Those who are the very best in their field did not specialize early and did not outperform as teenagers. Instead they had above-average but not excellent early performance, with sustained long-term development.

Here’s how the New York Times reported the study.

… the people who achieve the most later in life typically start off with less single-minded engagement across multiple disciplines, and less early success.

“When comparing performers across the highest levels of achievement,” the researchers wrote, “the evidence suggests that eventual peak performance is negatively associated with early performance.”

There are exceptions, of course, those rising stars who end up probing the outer limits of human capacity. Just look at Simone Biles or Mozart, whose exceptional abilities were evident in childhood. But more often, the long-term elites progress slowly and eventually surpass the wunderkinds.

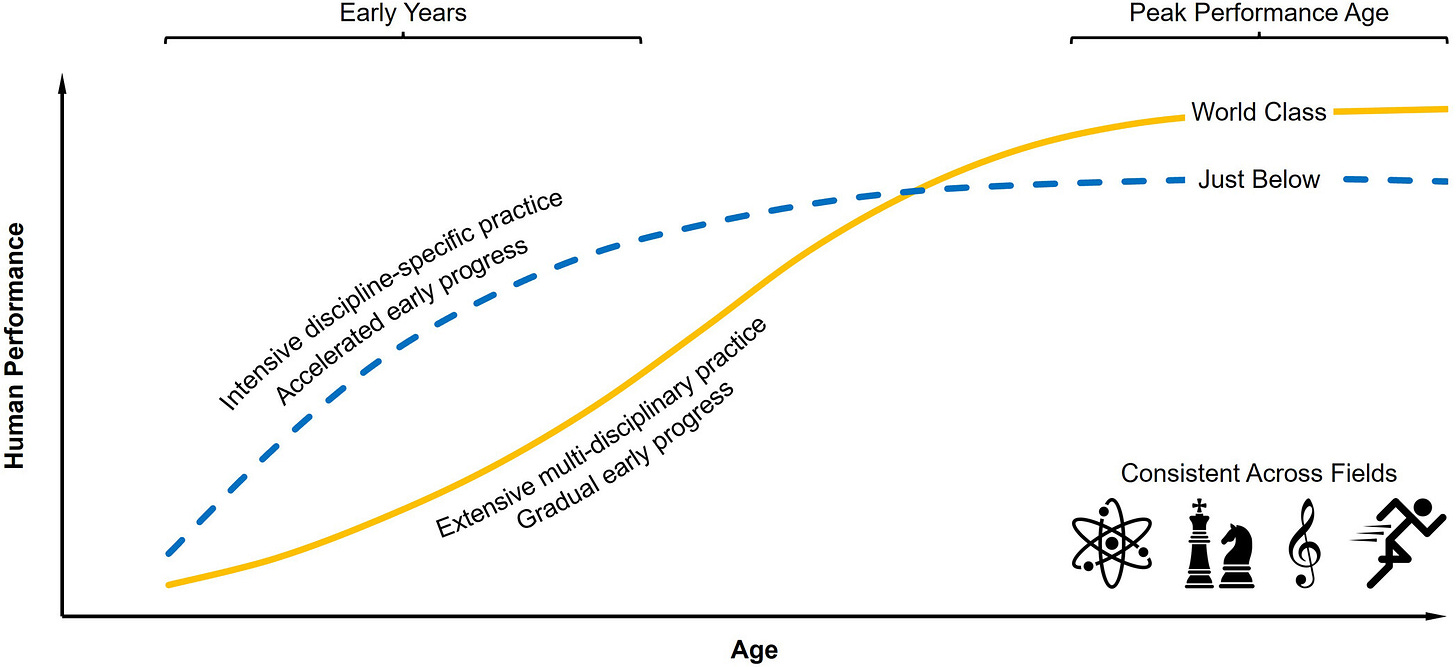

This is an exciting new finding. The study authors Arne Güllich, Michael Barth, David Z. Hambrick, and Brooke N. Macnamara, use this diagram to make the finding intuitively obvious. Their data comes from reviewing “19 datasets including 34,839 adult international top performers in different domains.”

One thing that stops people from diversifying in the way these authors recommend is the competency trap. Learning is hard and involves getting things wrong. Once we become competent at something we are less inclined to go back and learn something new. We know now that it will be difficult. As Mark Twain said,

We should be careful to get out of an experience only the wisdom that is in it and stop there; lest we be like the cat that sits down on a hot stove lid. She will never sit down on a hot stove lid again – and that is well; but also she will never sit down on a cold one.

When people enter into periods of high-achievement, whether early or late, it is because they are able to make changes in the way they work, open themselves up to incompetence.

Achievement is the result of transformation.

In Second Act I discussed a study, conducted by Lu Liu, Nima Dehmamy, Jillian Chown, C. Lee Giles, and Dashun Wang1 at Northwestern, which looked at hot streaks—intense periods of high achievement, lasting a decade or more.

The study found that before the hot streak begins there is an exploration phase, when new ideas are gathered, which is followed by a period of exploitation, when those new ideas are turned into original and impactful work.

This is similar to the explore/exploit dynamic, an idea from computer science, which says that to make the best decisions we should find the correct balance between gathering information (exploring our options) and making the most of what we know (exploiting that information). To make the best decisions, we need to balance exploration and exploitation.

Now, what matters most here is the change from explore to exploit.

What the research on artists, filmmakers, and scientists found was not that either exploration or exploitation alone was critical to a hot streak: it was the transition from explore to exploit that mattered. Exploring before exploiting means you can discover the most productive ideas and expand your creative possibilities. What matters is the switch.

The importance of this study is that late-blooming is not always age-dependent. Of course, sometimes there are age constraints. If you become a sports-star aged 25, you are a late bloomer in a way that a historian would not be. But as a general rule, late bloomers follow these patterns of behaviour, irrespective of their age.

Let me use Mozart as an example.

The authors of the new study acknowledge that “a fraction of gifted youth later become exceptional adults”, giving the examples of “composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, golfer Tiger Woods, chess player Gukesh Dommaraju, and mathematician Terence Tao”.

In Second Act, I actually claimed Mozart as a late bloomer. Discussing the “consistent probability theory of success”, I wrote:

…the more you do, the more chance you have of succeeding. It takes a lot of practice, deliberate and otherwise, to become successful. What matters in this rule is the accumulated expertise, not the starting point. Mozart, for example, was largely a prodigy because he started so young. He completed his decade’s practice before most people even begin theirs. He started composing aged six; twelve years later he composed his first breakthrough piece, the Piano Concerto No. 9 in E-flat major, K. 271. His earlier compositions are not as regularly recorded. Indeed, the pianist Víkingur Ólafsson described Mozart as a late bloomer, during a 2022 concert.

The Mozart repertoire that is still played, recorded, and bought most often begins somewhere around K. 331, which is Piano Sonata 11. You will all know this movement as soon as you hear it.

That was written in 1784, when Mozart was twenty-eight.

In 1786 he wrote The Marriage of Figaro and Piano Concerto 23. The two great symphonies were 1788. Mozart’s final year, 1791, was one of his very best. You can find plenty of splendid work earlier than this period. Symphony 29 was written in 1774, but the pattern holds.

The Clarinet Concerto was 1791. The great piano concertos are late 1780s, as are the great string quintets. Even if you enjoy the chamber music, as I do, it gets really good around K. 334, written in 1779. “Eine kleine Nachtmusik” was 1787.

Mozart was a prodigy, composing at five years old, but his truly great work came much much later.

The Mozart compositions widely regarded to be works of genius in fact seem to fit the new finding. Mozart was a prodigy, but he spent his youth touring, performing, and composing. Much of his work was the result of improvisations while performing, so rather than narrowly specializing, he was in fact an example of what this study found. Mozart learned both piano and violin as a child: exactly the breadth the study says leads to later success.

Mozart was learning everything a composer might need. He was not merely a piano prodigy, but a hard-working piano and violin player, performer of bravura piano concerts and a member of quartets, able to practice composing and improvising and to find synergy between the two.

He was the very opposite of a prodigy who focuses narrowly one piano practice. He was a slow-growing, wide-ranging late-bloomer.

‘Understanding the Onset of Hot Streaks across Artistic, Cultural, and Scientific Careers’, Nature Communications 12:1 (2021), p. 5392, https://doi. org/10.1038/s41467-021-25477-8

The conclusions of the Science study are a textbook example of collider bias: by studying only elite samples (where selection depends on both early and adult performance), the authors induced a spurious negative correlation that does not exist in the general population. Within the elite sample: if an athlete had low early performance but still made it into the elite sample, they must have had high adult performance (otherwise they wouldn't be in the sample). Conversely, athletes with high early performance could be in the sample even with moderate adult performance. This selection mechanism creates an artificial negative correlation. See here for more: https://zenodo.org/records/18002186

So you're telling me there's hope?